Frustrated by endemic poverty, corruption, and violence, Mexican voters delivered a clarion call for change in sweeping Andrés Manuel López Obrador to victory last July—bringing a leftist leader to power for the first time in decades in Mexico, Latin America’s second-largest economy. The president-elect takes office Dec. 12.

“With his election there is so much hope, and so many programs and projects are proposed—but so many things are not possible. Right now, the number one priority is to stabilize the country because investment, jobs, and growth depend on it,” said Lourdes Dieck-Assad, vice president for Hemispheric and Global Affairs for the University of Miami.

Dieck-Assad, who served as Mexico’s ambassador to Belgium and Luxembourg in addition to holding academic posts in Mexico, cited a recent survey indicating that 67 percent of Mexicans expect the new president to “do a good job,” yet nearly a third expect results in the first year.

“Hope is in the hearts of all the voters. There is change and there will be change, but where’s the money?” she asked, while urging Mexicans to be realistic and for the new political team to set priorities that will allow for reforms over time.

On Wednesday afternoon, UM’s Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas, led by Dr. Felicia Marie Knaul, invited a panel of scholars to examine the latest election and its ramifications. There is both concern and optimism.

López Obrador was not nominated by any traditional party but instead created his own, the National Regeneration Movement, or MORENA in Spanish. The acronym means “dark-skinned” and alludes to Mexico’s national patroness, Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“His victory is not just a turn to the left, it’s a rejection of the three most important political parties of the past 30 years. This is worrisome,” said Joy Langston, professor of political science at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas in Mexico City. Langston blamed the traditional parties for not “respecting the rules that they had made” to the political process, which left Mexican voters “no recourse” but to choose an alternative.

Her concerns centered on the continued or expanded rejection of institutions that may prompt Mexico to spiral toward the problems of other Latin American countries, such as Venezuela or Peru.

UM President Julio Frenk, who served as Mexico’s minister of health for six years during which time he reformed the health system and expanded access to previously uninsured Mexicans, echoed those same concerns.

Frenk described the president-elect’s supporters as a “broad coalition” and said López Obrador’s proposed cabinet includes “some elements that are extremely respected.”

“It’s a complex mix, and there will be an intense struggle within the party to see which [exercise control]. The rejection of institutions, with their checks and balances, poses a huge risk,” Frenk said. “Given Mexico’s position in the region and in global affairs, the next six years, starting when the new administration begins, will be crucial for the future of Mexico, the Americas, and the world.”

Knaul, the director of UMIA, moderated the discussion and asked the panel what they believe López Obrador hopes to achieve.

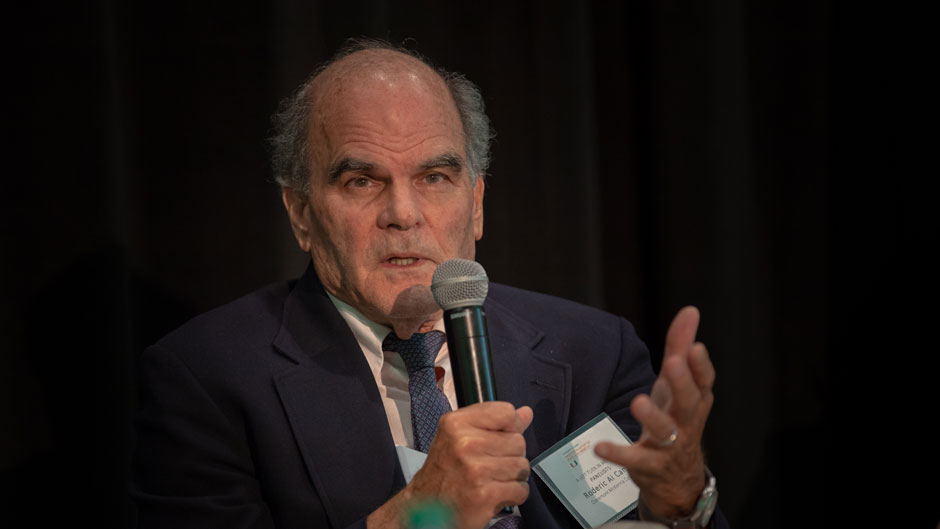

Roderic Ai Camp, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in California, responded that López Obrador was committed to the anti-poverty campaign he had launched while head of the Mexico City government and that he would prove good on his pledge to reduce wasteful government spending.

William Beezley, professor of history at the University of Arizona, suggested it is important to watch the decentralization process of moving ministries outside of Mexico City as promised by the president-elect.

Both Beezley and Marco Lara Klahr, professor of journalism at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, cited domestic violence as among the most serious problems facing Mexican society.

“Violence is the number one issue in Mexico and hidden under the spectacular number of murders and impunity is domestic violence—it’s endemic. The López Obrador administration has an opportunity to move forward to address this,” Beezley said.

A member of the audience questioned the state of U.S. and Mexican relations.

“The economy, not politics, is what counts. Rhetoric is easy—the question is are you able to govern,” responded panelist Langston. “The amount of pressure that the U.S. can bring to bear is minimal. The rhetoric on immigration and other issues about Mexico from the U.S. has been terrible, but that won’t affect López Obrador’s success.”

Ai Camp agreed that Mexicans have largely ignored many of the criticisms of their country and culture from the United States.

“The only impact that I detect is that, unfortunately, Mexicans are transferring their overwhelmingly unfavorable view of President Trump to an unfavorable view of you and me,” he said.

Sallie Hughes, faculty director and senior research area lead at UMIA, was instrumental in convening the panel discussion, the inaugural event of the recently formed Mexico-Mesoamerica studies group at UMIA.

“It’s so important to elevate the conversation on Mexico here on campus and in the larger community,” said Hughes, adding that more such events are planned.