Now there appears to be undeniable proof that it can be done—greenhouse gas emissions, which are superheating the planet, can be reduced considerably by curtailing our dependency on fossil-fuel-burning vehicles.

Over the course of just a few days, data from NASA and European Space Agency satellites have proved it.

What is regrettable, though, is that such validation has been spurred by a pandemic that has crossed oceans, killing tens of thousands of people, pushing the world’s economies to the brink of collapse, and straining health care systems beyond their capabilities.

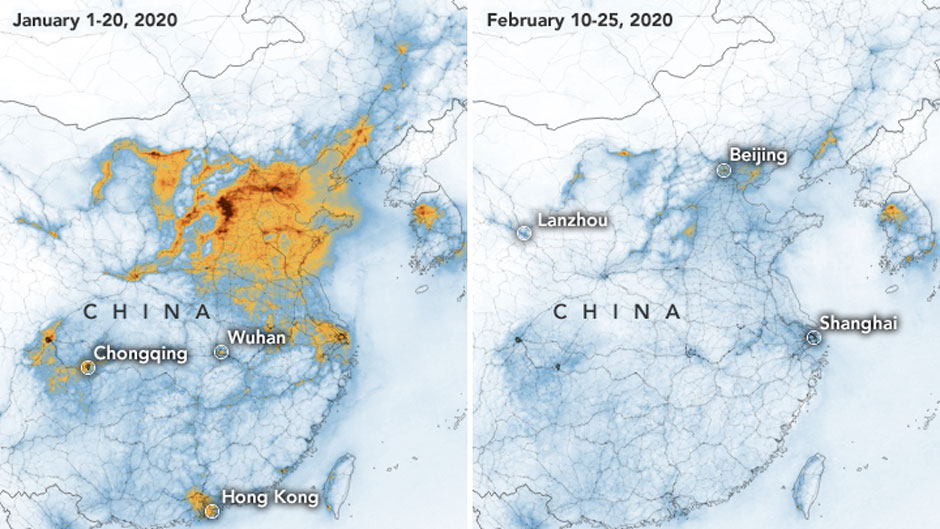

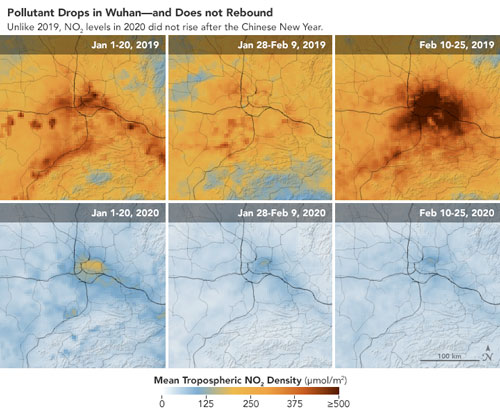

In their efforts to halt the unimpeded march of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, governments have imposed travel restrictions, issued stay at home orders, and, in extreme cases, instituted total lockdowns—all of which have reduced the number of cars on the roads and planes in the sky. In turn, atmospheric levels of nitrogen dioxide, which comes primarily from vehicle exhaust, have plummeted in countries around the worldwide—from China to Italy to the United States.

“We definitely are seeing the environmental benefits of shutting down our normal consumption of goods,” said Joanna Lombard, a professor in the University of Miami School of Architecture and a climate mitigation expert who holds a joint appointment in the Miller School of Medicine’s Department of Public Health Sciences. “The diminishment of transportation emissions is significant, and the reports from around the world show us glimpses of regeneration that occurs when we all step back.”

China experienced some of the most drastic reductions in nitrogen dioxide volumes. In January and February of this year, when a government lockdown was in place in the province of Hubei, the former epicenter of the pandemic, NO2 levels in the eastern and central regions of the country were as much as 30 percent lower than what is normally observed during that time of year, according to NASA.

Declines in emissions over Los Angeles, Seattle, New York, and other major metropolitan areas in the U.S. have also been documented.

And in Italy, where 60 million residents are under a total lockdown, Venice’s often-murky canals have cleared because there is no boat traffic on the waterways.

With fewer cars on the roadways, even wildlife stands to benefit.

“Less traffic and noise during the spring—which is breeding season for most birds, frogs, and mammals—is certainly much better for animals,” said Mauro Galetti, a tropical ecologist in the Department of Biology and director of the University’s John C. Gifford Arboretum.

But while the shutdowns have fostered unintended ecological benefits, they have come at a terrible price. “As we halt all the habits that fill our skies and roadways, we are incurring enormous economic hardship,” said Lombard. “And, as in the conversations about climate change impacts, the economic impacts of this pandemic are not felt equally across society.”

The shutdowns will eventually end. On March 25, for example, Hubei began allowing many of its residents to leave, as cases of new domestic infections in the province have subsided. And when the restrictions are lifted and people return to the normal way of life, atmospheric emission levels will begin to spike, experts warn.

“The evidence certainly suggests it,” said Naresh Kumar, an associate professor of environmental health at the Miller School.

Kumar, whose research centers on the global burden of environmental disease, monitors and records pollution levels in real time, providing the data to asthma, COPD, and other patients via smartphones and the web. In the coming weeks, he plans to analyze data from outdoor sensors that have been recording air quality over Miami before and during the outbreak.

In a study on emission levels in Beijing, China, during the 2008 Summer Olympics, Kumar found that 75 percent of the gains in improved air quality that resulted from the government shuttering factories and limiting vehicle traffic before and during the games was reversed within a year after the international sporting event ended.

“Given that combustion from automobiles is one of the major sources of greenhouse gases, I anticipate at least a 50 percent increase in air pollution within a week once normalcy is restored after the COVID-19 crisis,” he said.

Still, the pandemic’s unintended climate benefits, fleeting though they may be, have offered lessons on potential future actions that can be taken to keep temperatures in check and a climate catastrophe from occurring.

“It has been hard to achieve meaningful results in climate change policy because people have been reluctant to change their lifestyles. The steps needed were just too hard and too disruptive on our economy,” said Jessica Owley, a professor of law at the University of Miami, who specializes in environmental law with a focus on climate change law and policy.

“What we are learning now is that we can make changes when we need to,” Owley said. “Climate change is going to be even more devastating than this pandemic in terms of public health and impacts on our economy. Maybe the changes that we have made now without having a chance to even plan for them will help people see that we can all come together and make necessary sacrifices.”

The creative measures being implemented by municipalities and businesses to help stop the spread of COVID-19, such as work from home policies and cloud-based videoconference meetings, could endure long after the pandemic ends, some experts believe.

“People are putting a lot of time, energy, and resources into figuring out how to telecommute,” Owley explained. “We will learn that several functions can work well online. Municipalities should take advantage of the programs and equipment they are currently investing in and facilitate changes in public offices and services. I think we will see more telecommuting and perhaps changes in schedules.”

Owley, who attended the United Nations COP25 climate change conference in Madrid last December with six students from her U.N. Negotiations class, said the initial responses to the coronavirus crisis mirror, in some respects, our reactions to climate change.

“From world leaders to our neighbors, and perhaps even ourselves, we saw a denial that the pandemic was really as serious as people were saying,” she said. “We felt healthy, we went to the dinner parties, we flew to conferences. The changes we were being told were needed just felt so hard and unpleasant that we avoided them. People wouldn’t stay out of the bars when public health officials advised them to stay home. It took the government closing the bars for that to happen.”

At COP25, delegates were unable to agree on how to move forward with the mechanics of the Paris Agreement. But in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, that could change at the next summit “Now,” said Owley, “we have been given some idea of how to mobilize on big issues. We have also seen firsthand that disasters come whether you prepare or not, and a lack of preparation can exacerbate the problem.”

Architects and urban planners, said Lombard, have been addressing the climate crisis for years, designing walkable communities that place less dependency on cars. Perhaps now, amid the lessons that are being learned in dealing with COVID-19, those efforts will be ramped up, she said.

“One aspect of life at this moment is the number of people out walking,” Lombard said. “Where it is possible to do and still maintain a six-foot distance, people are out walking in their neighborhoods. And, where possible, people in front yards or on porches are talking to neighbors walking along sidewalks. So, the emergence of a better collective understanding of the importance of a self-sustaining neighborhood is reinforced in times of emergencies, and maybe that will inspire more movement in this direction.”

Amid the pandemic, the world is at “a moment of profound and rapid transition,” said Katharine Mach, associate professor of marine ecosystems and society at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

“The public health and economic consequences have been stark. In climate circles, there have also been questions about what we might learn relevant to climate transformations,” she said. “Historically, emissions of heat-trapping gases have slowed during times of economic recession. As economies rebound in the months to come, might there be opportunities to learn from everything that has suddenly shifted? Could some scientific gatherings be more efficient and richer remotely, rather than in person? Can we maintain vibrant social fabric and our closest relationships without constant travel? As the world continues to change day by day, we have much to learn from as we work hard together to keep everyone in society safe.”