While the streets and waterways of Miami may have remained quiet this spring, life was brimming inside the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

On one of his rare visits to campus this April, marine biology and ecology professor Martin Grosell was startled by a unique noise. Almost immediately, he recognized the low pitch that resembles a boat whistle. It was the mating call for Gulf toadfish, something he had only heard on a recording before.

“It’s very distinctive,” said Grosell, whose Environmental Physiology and Toxicology lab examines how fish cope with natural and human-created environmental change. “And it’s surprising how loud it is, even while they are completely submerged.”

The noise was not completely unexpected, but its presence was encouraging. Grosell was hopeful that it meant new toadfish were on the horizon. At the time, Grosell and his Ph.D. student, LeeAnn Frank, as well as marine biology and ecology professor Danielle McDonald and her lab team, had all but given up on their attempts to breed toadfish. They had started the process in January, when toadfish mating season typically begins.

“We didn’t really think it was going to happen,” Frank said. “It had been months. Then the quarantine happened, and one day I was siphoning the water [to clean the tanks] when I saw an egg and stopped.”

A few days later, Frank found two nests inside PVC tubes typically placed in the tanks, each containing scores of embryos that were being fiercely protected by two male toadfish. In total, two of the eight fish couples produced 400 juvenile toadfish, which are now being cared for (they eat brine shrimp twice daily) in the two fish physiology labs on Virginia Key.

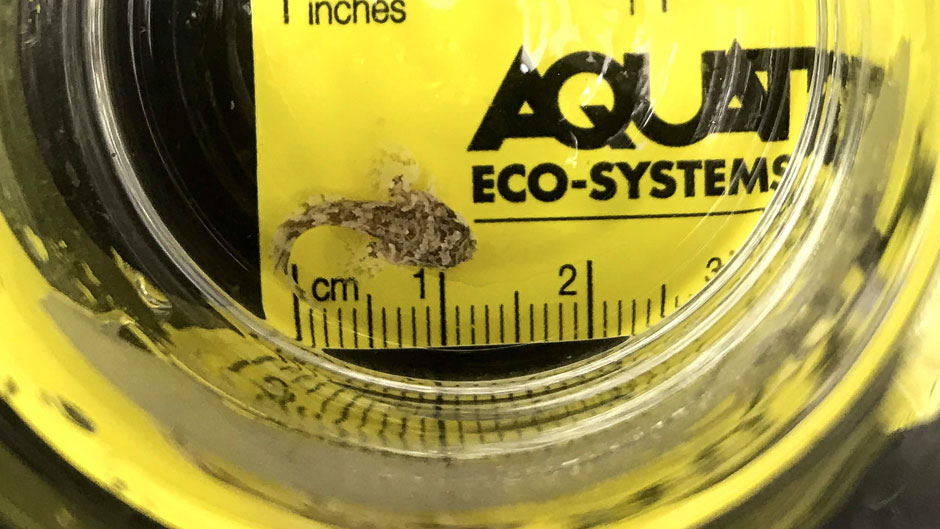

McDonald and Grosell—who are sharing custody of the newborns—said they were both ecstatic to see that their experiment worked. Grosell and McDonald have excitedly posted updates on their labs’ social media pages as the tiny juvenile toadfish have been eating and growing. They have already doubled in size since birth but are still just short of two centimeters long.

“This is probably the first time that targeted captive breeding of toadfish was attempted and definitely the first time at UM,” Grosell said.

The fish may have simply needed some privacy, the researchers joked, but they also wondered if the tranquil conditions caused by COVID-19 precautions—with rare human contact—are necessary to help toadfish communicate and reproduce.

“We don’t know if quiet conditions are critical or not, but next year we will be extra careful about isolating these animals because it very well could have been,” Grosell added, saying they plan to publish research about the breeding process.

A lot of factors need to align for toadfish to spawn. First, the female needs to be gravid, or have eggs able to be fertilized (to fulfill this caveat, the team used an ultrasound technique to ensure the females they chose for breeding had eggs). Then, the female must notice the male and lay the eggs in his chosen nest spot, where he then fertilizes them and protects them until they swim out of their egg sacs.

Video: TJ Lievonen/University of Miami

Although the lab uses PVC pipes as a haven for toadfish, in the wild, male toadfish often build nests between pilings, in a conch shell or even inside an old soda can. They alert females to the area with their distinctive boat whistle-like call, McDonald said. After the eggs are fertilized, the male toadfish watches over the larvae for about a month, fanning his tail constantly to aerate the larval fish until they swim away.

“Another reason we have been excited to see this process is that larval toadfish look identical to adult toadfish within a few days—they’re just miniature versions of the parents,” said Maria Cartolano, a Ph.D. graduate who led the ultrasound method with the help of master’s candidate Emily Milton and has researched how toadfish communicate for reproduction through McDonald’s lab.

So, why did they want to breed toadfish? McDonald said that in the past, their labs have gotten toadfish as unwanted catch from shrimp fisherman. But lately, shrimp have been harder to find, and therefore, so have toadfish. With help from the University of Miami Experimental Hatchery, her lab team worked on a plan to breed toadfish so they would not have to buy them.

“We know a lot about these fish and yet we never attempted to breed them, but we were desperate this year,” said McDonald. “It worked, and hopefully we’ll get it to work every year.”

Gulf toadfish are one of the most abundant species in Biscayne Bay and the coastal areas in the Gulf of Mexico. Although they often get a bad reputation from fishermen because they are aggressive and may bite, both Grosell and McDonald find them fascinating because of their tolerance to less-than-optimal ocean conditions and their critical role in the ecology of Biscayne and Florida Bays. For example, Grosell explained, Gulf toadfish serve as a major food source for bottlenose dolphins and mangrove snapper. In addition, Grosell has also explored how toadfish, like other marine fish, must ingest high volumes of saltwater and then produce calcium carbonate in the ocean, which mitigates some of the effects of ocean acidification.

McDonald exclusively studies toadfish and focuses on how they respond physically to contaminants in the ocean, as well as other stimuli.

“It’s hard not to love toadfish,” McDonald said. “They are very hearty and have a lot of evolutionarily derived characteristics that make them interesting—such as a specialized kidney, their high tolerance to air exposure (some can live for up to a day out of water), as well as their ability to survive with low oxygen levels in the water.”

McDonald spends most of her time investigating the role of cortisol (the stress hormone) as well as serotonin in toadfish. In humans and fish, serotonin is a chemical in the brain that works as a mood stabilizer, but it also impacts many of our bodily functions. In humans, McDonald said research shows that serotonin plays a role in migraines, irritable bowel syndrome, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease. So, learning about how these function work in toadfish can shed light on how they may operate in humans.

Although they have studied adults in the past, now McDonald and Grosell may expand their research to learn more about juvenile toadfish.

“The more information we can find out about how these mechanisms work, whether we are working with humans or fish, can eventually benefit human health,” McDonald said.