To understand just how much Luis Glaser cared for University of Miami students, just ask a former undergraduate who credits the longtime executive vice president and provost with helping her fulfill a lifelong dream of becoming a physician.

“I can vividly remember having a one-on-one meeting with him where he asked me about my hopes, my ambitions. He did not hesitate to help me, picking up his phone and calling an admissions’ official at the Miller School of Medicine to advocate for me,” recalled Terri-Ann Bennett, now a practicing obstetrician and gynecologist in New York. “I was just a young, immigrant woman from an impoverished background, but Dr. Glaser saw what I could become.”

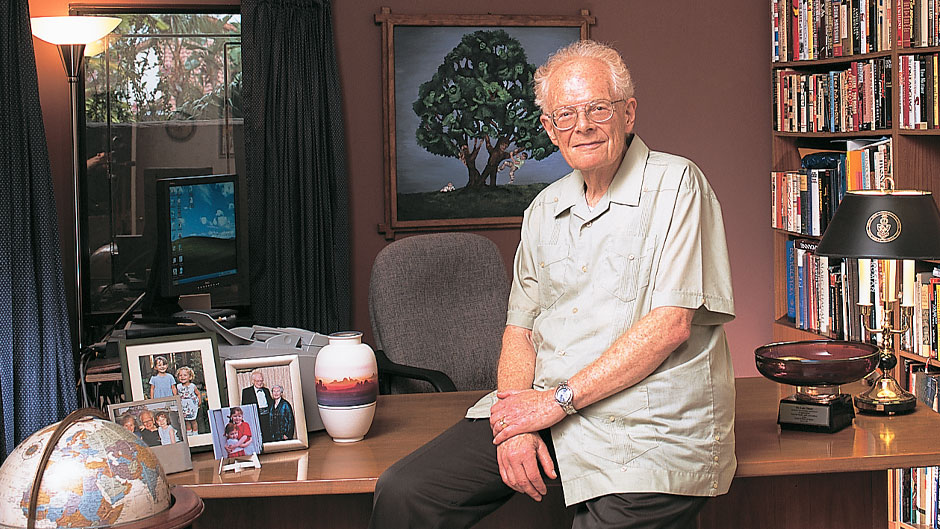

Glaser, who for nearly two decades as provost helped the University of Miami shed its image as Suntan U and become one of the nation’s leading private research institutions, passed away on Dec. 23. He was 88.

“A brilliant administrator, researcher, and scholar and a champion for faculty and students” is how Jeffrey Duerk, the University’s current executive vice president for academic affairs and provost, described Glaser.

“I met him early in my tenure here as provost, and he was gracious in offering perspective, guidance, and advice,” said Duerk. “It’s been an honor to follow in his footsteps, and I am indebted to him and saddened by our shared loss.”

Glaser, who was provost from 1986 to 2005, served under two University of Miami presidents, first Edward “Tad” Foote II and later Donna Shalala. During his 19 years in that role, the University grew and improved exponentially, opening new schools and colleges, creating new academic programs, and increasing its competitive research funding by hundreds of millions of dollars.

He was passionate about academic excellence, helping many students make it to medical school. Glaser also helped to attract and retain exceptional faculty members, recognizing their achievements at the annual ceremony of the Provost’s Award for Scholarly Activity, which started under his watch.

“Charming or tough when appropriate, loyal and nurturing, he gave his deans the independence to lead their schools and colleges, rarely telling them what to do or how to do it,” said David Lieberman, former senior vice president of business and finance, who worked closely with Glaser for more than 20 years.

Mary Sapp, former associate provost for planning, institutional research, and assessment, would meet regularly with Glaser to discuss her office’s analytic studies and to work on the University’s annual strategic plan. “He was always interested in using our reports to find ways to improve the University, often asking for follow-up analyses to deepen his understanding,” she recalled.

On one occasion, she and Glaser worked on a report that would be presented to the University’s deans and Faculty Senate that showed the impact of first-semester grades on student attrition. “Despite a concern at that time about grade inflation, he was able to obtain support for a variety of programs to help students earn higher grades: free tutoring, opening the Writing Center and math lab, and revising GPA requirements for retaining scholarships. The following year, retention of first-year students jumped a remarkable 8 points,” she said.

Despite the demanding pressures and time-consuming duties that came with being provost, Glaser, who had a Ph.D. in biochemistry, still found time to teach—engaging with students and showing a genuine interest in their academic progress.

He co-taught the cross-disciplinary “Ethics and Genetics” course with Stephen Sapp, emeritus professor of religious studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. “He never missed class, was always exquisitely prepared, and read every paper we assigned,” Sapp remembered. “Luis and I had a blast going back and forth in class, often to the surprise of students early each semester until they finally caught on to how much we really liked each other.”

Glaser also found time for students outside the classroom, visiting the residence halls during the holiday season to read “How the Grinch Stole Christmas.” Students would sign the book after his reading.

“He was so kind and simply loved and cared for our students. He was the consummate professional and a terrific and brilliant scholar, and I was so lucky to have worked closely with him,” said Patricia A. Whitley, vice president for student affairs.

“Luis genuinely cared about, believed in, and supported the people he worked with, which in turn created a loyal team who wanted to do their best for him and the University,” said Perri Lee Roberts, emeritus professor of art history. “No employee who witnessed Dr. Glaser wearing a Santa hat while stirring a pot of some secret Viennese brew at the annual holiday Ashe Bash will have forgotten the sight or the sentiment. For me, he was a second father, a mentor, a role model, and a dear friend.”

Even after Glaser retired from his role as provost, he continued to maintain close ties with the institution, often stepping into temporary positions at the request of University leadership. When Sam J. Yarger, dean of the School of Education, passed away unexpectedly in 2005, Glaser stepped in and served as interim dean for a year until a new dean was appointed. In his other post-provost roles, he served as vice provost for research on the medical campus and once headed up the Master of Arts in International Administration program.

“He was probably the smartest person I have ever known,” said Steven G. Ullmann, a professor in the Department of Health Management and Policy at the Miami Herbert Business School, who served as Glaser’s vice provost for faculty affairs and university administration for 16 years.

Glaser’s reputation transcended borders, Ullmann said. One year, when Ullmann was checking into a hotel in Jerusalem, he encountered a professor of biochemistry from the University of Pennsylvania. Striking up a conversation with him, Ullmann asked the professor if he knew Glaser. “He turned to me and said, ‘Of course I know Luis Glaser. Everybody knows Luis Glaser. Luis is Nobel Prize-winning material,’ ” Ullmann shared.

Glaser spoke four languages: English, German, Spanish, and Yiddish. During Hurricanes football games, he would sometimes be interviewed on Spanish-language radio stations at halftime.

Elizabeth Markowitz, Glaser’s executive assistant for the last seven years of his term as provost, remembers him as having a knack for numbers. “He knew every statistic for anything and everything about the University—admissions, business operations, treasury, financial, student affairs. All of it, and for every school and college, including medical,” said Markowitz.

Once, Markowitz handed Glaser a three-ring binder thicker than a telephone book, watching him as he flipped through the many pages of reports that were to be presented at a Board of Trustees meeting. He stopped at one particular page filled with numbers. “He glanced at it for less than five seconds and said to me, ‘This number is incorrect,’ ’’ she said. “I looked at him in disbelief, and he just smiled. After I contacted someone about the number, it turned out that he was right. I don’t know how he was able to do that, but it just solidified for me that there was only one Dr. Glaser.”

Luis Glaser was born on March 30, 1932 in Vienna, Austria, the son of Hermann and Gisela (Kohn) Glaser. Shortly after Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1939 and Glaser’s father, a physician, was told he could no longer practice medicine in the country, the family moved to Antwerp, Belgium, for a year, and then to Mexico City, where Glaser grew up.

He graduated from the University of Toronto and then earned his doctoral degree at Washington University in St. Louis, studying in the lab of Nobel laureates Carl and Gerty Cori and eventually becoming a professor and chair of biomedical sciences at that institution. At Washington University in St. Louis, he also met his wife of 59 years, Ruth.

Above all, Glaser was dedicated to his family and “always found time for us,” said his daughter, Miriam Lipsky, director of student affairs assessment and projects at the University of Miami. “He was a huge influence in our lives. He was always there to lend an ear, to listen and share his thoughts and opinions, whether I was trying to work out what I would write for a paper or if I was having a personal problem and just needed advice. That’s just how he was,” she pointed out.

“When I would call him to ask for advice, he’d usually say, ‘Let’s go to lunch,’ and he truly enjoyed that one-on-one time,” Lipsky added. “Later, when my daughters were UM students, they would often join us for these lunches, and that made my father even happier—to have three generations of ’Canes together.”

In addition to his wife Ruth and daughter Miriam, Glaser is survived by daughter Nicole Glaser and granddaughters Megan, Maya, Lauren, Elie, and Cianna.