A team of University of Miami School of Architecture students led by Sonia Chao, research associate professor, will be in Nantucket, Massachusetts, next week to participate in the community presentation of the “Envision Resilience Nantucket Challenge,” a competition that tasked participating teams with reimaging how Nantucket, a small island off Cape Cod, could meet the challenges of climate change and sea level rise.

Although Nantucket is 1,500 miles away from Miami, the threat of sea level rise is something both places share. It is estimated that by 2040, Miami could see 21 more inches of sea level rise. By 2100, that increases to 120 inches, according to the Unified Sea Level Rise Projection 2019 Update released by the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact.

“If you are at University of Miami School of Architecture and are not yet familiar with sea level rise, you haven’t been going to class,” said student Tanner Wall, who is part of the cohort. “We are thinking about coastal resilience in every single class we take; it’s a core part of the curriculum.”

Chao—who is the director of the School of Architecture’s outreach arm, the Center for Urban and Community Design, and is also co-director of its interdisciplinary Master of Professional Science in Urban Sustainability and Resilience program—was invited by Envision Resilience to lead a University of Miami team. Dean Rodolphe el-Khoury was supportive of the multi-institutional and interdisciplinary format of the course from its onset.

Three of the four students participating in Chao’s fall course, An Introduction to Resilient Building and Community Design, began their analysis of Nantucket aided with research carried out by a graduate student class and graduate teaching assistant Michael M. Ganom.

“There are several similarities, as well as contrasts, between Miami-Dade County and Nantucket, which make a comparative analysis interesting—from their tourism and port-based economies, iconic National Register Historic Districts, and their Atlantic Ocean-driven climate realities to their diverse scales, socioeconomic conditions, and terrain. And for these reasons, I wanted our students to be a part of this rich learning experience,” said Chao.

Equipped with the research, Wall, Thomas Long, Camila Zablah, and Paula Christina Viala continued work in their Special Problems course in the spring semester.

To prepare for the challenge each student participated in charrettes organized by Chao that looked at Nantucket’s history as a whaling community, its architecture—which includes many cedar-shingled buildings—its urban patterns, and geology.

They also discussed its economy and tourism industry. Nantucket is a popular summer destination with tourists who are attracted to its dune-backed beaches and luxury shops and restaurants.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic suspended travel, the students had to rely on virtual lectures and meetings. Every week they would hear lectures from distinguished professors and local experts. These included presentations from Allan Shulman, professor at the School of Architecture, and Jennifer Korberg, research supervisor of the Nantucket Observation Foundation.

The project the students will present is a master plan of the entire Nantucket area: Brant Point and its waterfront estates, the downtown, and the historic district along Washington Street, a main commercial artery of traffic.

“We are proposing the community learn to live with water, as drastic changes to the waterfront are imminent,” said Chao. “You just cannot save everything, and you have to start making hard choices. But that does not imply that the future of Nantucket is bleak. The image of the city will transform but its connectedness to its culture and traditions are well ingrained and will inform the making of a new Nantucket. A master plan connects all the aspects of the envisioning process.”

Among the highlights of the plan:

- Retreat buildings from low-lying areas to the highlands, an area that is above sea level to create a “New Nantucket.” These may include historic buildings that are on the National Registry.

- Allow for other buildings to “adapt in place” by refurbishing them with stronger building codes. “New buildings should have a higher design elevation and impact windows to minimize damage in case of storm surge,” according to Viala.

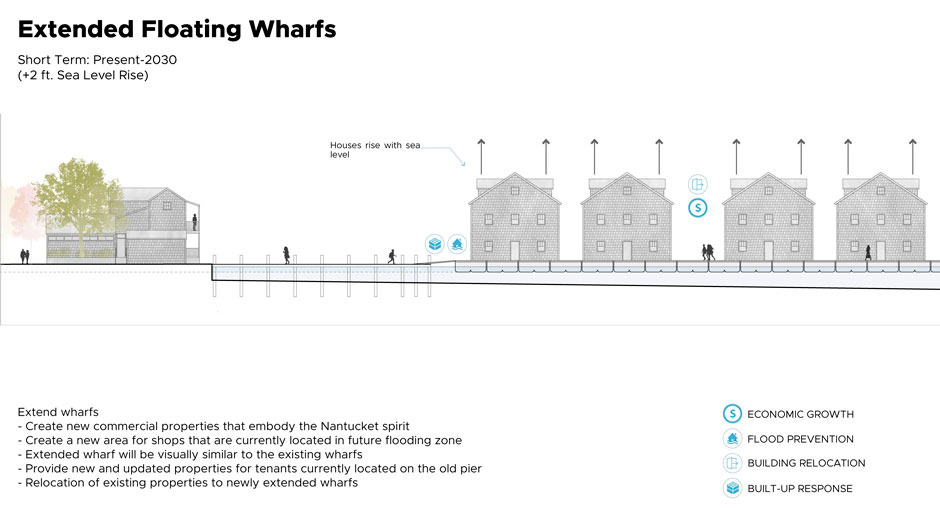

- As part of a Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) program proposal, students recommend the conversion of the downtown’s finger piers into “floating docks” (islands) to create a new main street environment, with a mix of uses that allow for waterfront commercial activities.

- Just beyond the downtown area, build elevated mixed-use buildings, with affordable housing for workforce and space for stores and restaurants in a new waterfront, Stiltsville-inspired Fisherman’s Village.

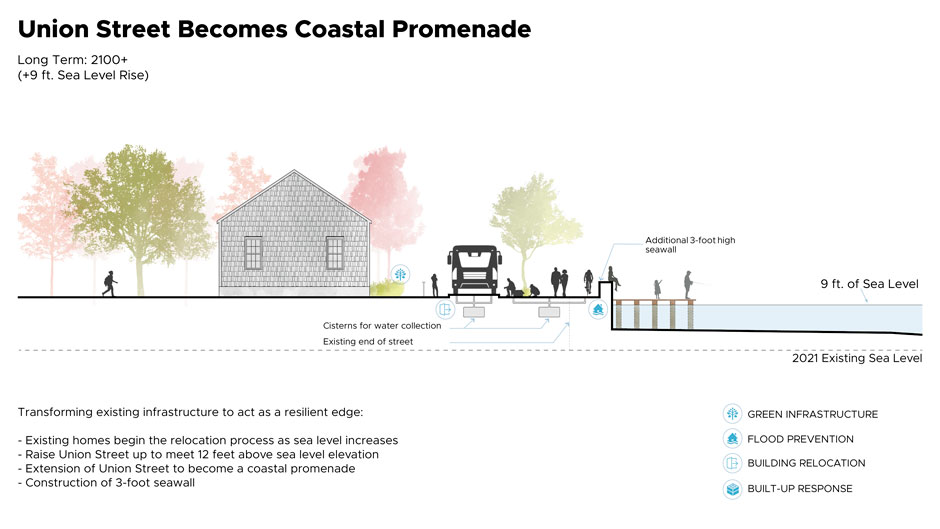

- Rising seas will move the waterfront back in the short to mid-term, thus in response the proposal illustrates the ways to plan for this change in the urban landscape and to begin with transforming existing Union Street to accommodate transportation, mixed-uses, and waterfront activities.

- In the highland neighborhoods, introduce linear parks by transforming the street section of several roads. Host tree canopies that allow for pedestrian mobility, bicycling, and social interactions, which result in a lower carbon imprint.

- In the high-end residential area of Brant Point, many portions were built over reclaimed salt marshes. The plan calls for relocation of houses to higher ground through the TDR program.

- Along the beaches of Brant Point, sand dunes would be enhanced as well as buttressed by boardwalks to allow for safe pedestrian traffic.

- In order to mitigate storm surge, Chao’s students reached out to Diego Lirman, an associate professor in the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, to learn more about seagrasses. They also contacted Landolf Rhode-Barbarigos, an assistant professor in the College of Engineering, to learn more about the recently developed sea hive system, which entails placing sea hives on the beach, and in some instances, just off shore or along seawalls. As the system is flexible, it can be employed in a variety of settings. It was designed through advanced physical testing at the Alfred C. Glassell, Jr. SUSTAIN (SUrge-STructure-Atmosphere Interaction) Laboratory and can additionally serve to harvest oysters and other mollusks. The 3D geometrical pods can encourage the growth of sea grass, which can mitigate storm surge and reduce wave action.

Other schools invited to lead a team included the University of Florida College of Design, Construction and Planning; Harvard University Graduate School of Design; Northeastern University College of Arts, Media, and Design; and Yale University.

Next Tuesday, an exhibition will open on the island to showcase all the Nantucket Challenge proposals. The exhibition ends in December.

On Wednesday, during a community gathering hosted by Envision Resilience, Chao will join faculty members from the other institutions to give an overview of the project. The students will present their project directly to the local community and later have the opportunity to engage with academics and fellow students.