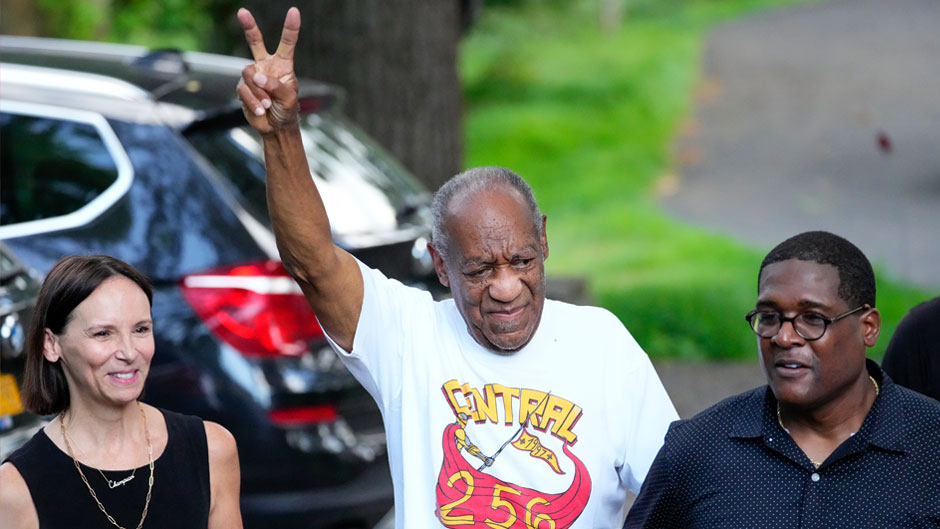

After serving almost three years of a three- to 10-year sentence for indecent assault, Bill Cosby walked out of a maximum-security prison last Wednesday a free man. His conviction was overturned by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which ruled that the once-celebrated actor’s due process rights were violated.

In a 79-page opinion, the court ruled that the prosecution violated Cosby’s right against self-incrimination by using statements at trial that the 83-year-old actor made during depositions in a civil case.

Cosby, once known as “America’s Dad,” was convicted on three felony counts of aggravated indecent assault in 2018 for drugging and assaulting Andrea Constand in 2004. It was the first major case of the #MeToo era.

The court’s decision reversing Cosby’s conviction stems from a 2005 decision by then-Montgomery County district attorney Bruce Castor, who doubted Constand’s allegations would hold up in court.

“Castor determined that he could never win a criminal conviction, and so he decided to force Cosby into testifying in Constand’s civil case,” said Tamara Rice Lave, professor of law and director of the Litigation Skills Program at the University of Miami School of Law. “He did that by publicly stating that there would never be a criminal prosecution, which meant Cosby, in a civil case, could not invoke his Fifth Amendment right to silence.”

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that Castor’s decision not to charge the comedian was binding on his successor, who reopened the case and charged the former “Cosby Show” star in 2015.

The ruling, which also bars a retrial of the case, drew mixed reactions, with #MeToo supporters expressing outrage and legal experts saying that the decision, while disturbing to some, is correct in that it demonstrates that everyone is entitled to the privilege against self-incrimination found in the Fifth Amendment.

“It’s tempting to look at this ruling and say it’s unjust, that the world is falling in,” Lave said. “But we have to remember that our legal system of rules works because people follow the rules. If a prosecutor is allowed to do what happened in this case, why would anyone trust the system?”

Lave, who was a deputy public defender in San Diego for 10 years, said that she initially took on that role with the mindset of defending the innocent but quickly realized that serving in that capacity meant fighting for “a system to make sure it is fair, to make sure it is balanced,” she said. “And that’s what this case is about: ensuring balance and fairness and that there is no prosecutorial overreach. If the prosecutor had been allowed to get away with this, it would have been a shocking violation of constitutional rights. And everyone has constitutional rights, even people who are accused of terrible things.”

Lave—who handled cases that ranged from torture and rape to murder and sexual assault—and College of Arts and Sciences faculty members Louise K. Davidson-Schmich, Claire Oueslati-Porter, and Alex Piquero answer other questions surrounding the recent ruling.

Could the ruling have any implications for a Harvey Weinstein appeal?

The ruling has no impact on the Weinstein case. Cosby appealed on two grounds: use of his deposition statement and admission of uncharged misconduct—testimony by alleged victims about prior drugging and sexual assault. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in Cosby’s favor on the first issue, and so it never considered the second.

—Tamara Rice Lave, professor of law in the School of Law

How much of a blow could the ruling be to the #MeToo movement, and will it discourage other victims of sexual assault from coming forward?

Although this will be viewed by many as “someone getting off on a technicality,” I think that it may actually embolden and strengthen the #MeToo movement insofar as they can call attention to the perceived injustice. My sincere hope is that it does not discourage victims of sexual assault from coming forward, especially now given the increases we have seen in domestic and intimate partner violence during COVID-19-lockdowns. But this will take local, city, state, and federal leaders and partners to ensure that the resources and assistance that survivors need, not just in the legal system but in their lives, are protected and ensured. Fortunately, President Biden has earmarked substantial funding in this area, and I hope that these resources are expanded and scaled up to provide as much resource and support as needed now and into the future.

—Alex Piquero, professor and chair of the Department of Sociology

Cosby’s conviction was overturned due to a procedural discrepancy, not because Cosby was exonerated. There are larger issues regarding justice for sexual assault survivors. Incarcerating sex offenders is unlikely to end the problem of sexual violence in our culture. To change our culture’s high rate of sexual violence, deeper systemic changes are needed. This is the work that Tarana Burke, who incepted the #MeToo movement, and many other activists and supporters are doing.

—Claire Oueslati-Porter, senior lecturer and interim director of the Gender and Sexuality Studies program

It takes considerable courage for victims of sexual assault to come forward and name their attackers, especially when the perpetrator is a famous person. The news from Pennsylvania certainly won’t make it any easier. However, it is important to note that, in this particular instance, Cosby’s conviction was overturned not based on the facts of the matter but due to procedural errors in the handling of his case. The court decision does not dispute that he drugged and assaulted Andrea Constand and he did serve three years of his three- to 10-year sentence before the conviction was overturned.

—Louise K. Davidson-Schmich, professor of political science