When Hawaii native Carissa Moore rose from the roiling sea east of Tokyo on Tuesday to claim the first women’s gold medal in the new Olympic sport of surfing, she was widely regarded as a most fitting champion—the embodiment of legendary surfer Duke Kahanamoku’s dream of seeing surfing in the Olympics.

“Surfing is Hawaiian. It was the Hawaiians who developed it into a sport. It was the Hawaiians who view surfing as an integral part of their culture and society,” said Martin Nesvig, a University of Miami history professor who recently taught a class on how Hawaii’s surf culture changed the world. “So, it’s really great that someone is bringing the gold back to Hawaii. In so many ways, the sport belongs to Hawaii.”

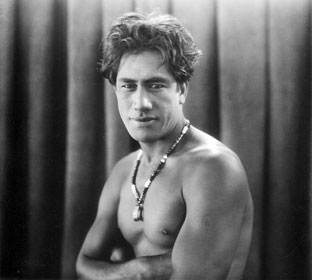

Photo: Library of Congress

While not yet a household name, Moore is a four-time world champion whose hometown of Honolulu had already declared Jan. 4 as a holiday in honor of her significant accomplishments. Far more well-known is Kahanamoku, a captivating figure central in the course Nesvig taught for the first time last semester. A five-time Olympic medalist in swimming, Kahanamoku expressed his hope of seeing surfing in the Olympics during his first trip to the podium at the 1912 Stockholm Games.

“Duke was one of the main people in the teens and 1920s who introduced surfing to the rest of the world,” said Nesvig, who ordinarily focuses on 16th- and 17th-century Mexican history, particularly the Spanish conquest, inquisition, and Catholicism. “He traveled the world doing demonstrations in the surf and would draw thousands of people who were fascinated by this sport they had never heard of. He was really instrumental in bringing Hawaiian culture to the rest of the world where it was not well known.”

Introducing students “to a radically different culture” was one of Nesvig’s main goals in developing a course that he said is really out of his comfort zone. But the surfing class evolved from another rather unique history course on a subject Nesvig was more familiar with. A native of San Diego who left his surfing days behind when he moved to Miami Beach to join the faculty in 2005, he has long been obsessed with coastal cultures and began teaching the history of beaches about nine years ago.

Offered periodically, that class covers a range of topics, including bathing suits, tourism, shipping, fishing, real estate, public access, and the Jim Crow-era policies and practices that, until 1965, barred Black people from Florida’s beaches. Similar attitudes, Nesvig said, prevented Kahanamoku from staying in beachfront hotels when he traveled the world, and from playing Tarzan in Hollywood. He was considered “too dark-skinned” for the movie role, and his friend and swimming rival Johnny Weissmuller landed the part instead.

“Every time I taught the beach class, everyone, including me, was kind of sad when the Hawaii segment ended. They were like, ‘Oh, but we want to keep going, it’s so interesting,’ ” recalled Nesvig, who speaks fluent Spanish and has a “decent” Hawaiian vocabulary. “So, the more I taught about Hawaiian history, the more I thought this material is just too good to pass up and I developed it into an entire class just about surfing and Hawaii.”

Titled “Hawai’i and the Pacific World: Or, How Surfing Colonized California and the World,” Nesvig plans to offer it again next fall. The course traces how the 50th U.S. state went from being a kingdom with a complex and sophisticated culture to a missionary outpost to a U.S. territory that disenfranchised native Hawaiians—and tried to suppress the sport that was so intertwined with the cultural fabric.

“I loved it,” said rising senior Rachel Stempler, one of the 43 students and few history majors who took the inaugural class. “I learned so much about Hawaiian history that is so relevant to the world today. What was really fascinating about Duke was he wasn’t just an amazing athlete. He founded an organization that fought colonialism and was involved in the resistance movement against white supremacy.”

Just like how some people today scoff at surfing’s admission into the Olympics, Nesvig indicated that Calvinist missionaries regarded it as a waste of time and spearheaded laws to make it illegal, for example, to surf on Sundays. “They basically said surfers are a bunch of losers and lay abouts who need to get to work,” he said. “But surfing was never really suppressed. In the areas that had large concentrations of white missionaries, like Honolulu and the west coast of Maui, social pressures and economic penalties prevented surfing during workdays, but in the rest of the island chain surfing never really died out.”

Yet, just like the Spaniards’ arrival in Mexico brought diseases that wiped out indigenous Mexicans, Nesvig said, the arrival of westerners in the 1790s brought diseases that decimated native Hawaiians. Today, he noted, those who can trace their roots to precolonial Hawaii are estimated to be less than 15 percent of the population.

Still, thanks to the efforts of legendary figures like Kahanamoku, who was elected Honolulu’s sheriff 13 times, and new generations of Hawaiians like Carissa Moore, surfing and its influence on the culture aren’t going away.

“Just look around at what students wear on our campus. A lot of the clothing originally designed as surf gear—flip-flops, Vans, and clothing like Hurley and Billabong—are now just mainstream, hot-weather clothing,” said Nesvig, who wholeheartedly agrees that surfing belongs in the Olympics. “It’s a very serious and dangerous sport that requires a high level of skill. People break their legs doing it. They get concussions. They get attacked by sharks. They drown. But you can’t keep them from chasing waves.”