A new study led by scientists at the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies and NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML), and NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service Habitat Conservation Division, reveals that sediments lingering near dredging sites can have long-lasting harmful effects on the early life stages of coral if they are re-suspended, even during brief events like coastal storms.

These new findings are particularly significant for South Florida, where dredging during the upcoming expansions of two major ports—Port Everglades and Port Miami—could further impact the coral reefs in the vicinity.

“Our findings highlight the importance of setting environmental “stand down” windows, or temporary moratoriums on dredging operations, before, during and after coral spawning to prevent negative effects on larval settlement,” said the study’s lead author Xaymara Serrano, a previous assistant scientist at the Rosenstiel School-based Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS).

To conduct the study, the researchers exposed larvae from the mountainous star coral (Orbicella faveolata), which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, collected near the Port Miami channel to low and high doses of suspended sediments for 24 hours. They compared three parameters—larval survival, settlement and respiration—with larvae exposed to reef sediments from the natal reef of the parent colonies in the Florida Keys, as well as with larvae that received a no sediment treatment. The researchers also examined the microbial communities in the sediments from both sites to evaluate their potential effects on coral larval performance.

The results revealed that coral larvae exposed to sediments from near Port Miami had significantly lower survival and settlement rates compared to those exposed to reef sediments or the no sediment treatment. Additionally, the sediments from near the port harbored different microbial communities compared to reef sediments, including higher levels of bacterial groups linked to coral disease.

“Our findings stress the importance of carefully planning and managing dredging to minimize impacts on corals and reefs,” said the study’s senior author Andrew Baker, a professor of marine biology and ecology at the Rosenstiel School. “They also underscore the need for long-term monitoring to detect increased sedimentation, turbidity, and potential contaminants from dredging.”

The researchers suggest that a temporary moratorium on dredging take place the months of predicted coral spawning, as well as period of 2-3 weeks after spawning.

Major reef-building coral species, including Orbicella faveolata, are facing extinction due to stressors like temperature-induced bleaching, diseases, and coastal pollution, leading to long-term declines in Caribbean coral populations. To develop effective conservation and recovery plans, it's crucial to identify the factors causing recruitment failure. Our study aims to illuminate these "bottlenecks," such as the impacts of sedimentation on settlement into suitable reef habitats.

The study was published on June 26, 2024 in the scientific journal PLOS ONE. The study’s authors include: Xaymara Serrano, Stephanie Rosales, Ana Palacio-Castro from CIMAS and Olivia Williamson and Andrew Baker from the Rosenstiel School. This study was funded by NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program (Project ID 31147) and MOTE Protect Our Reefs grants (POR-2015-15 and POR-2016-16).

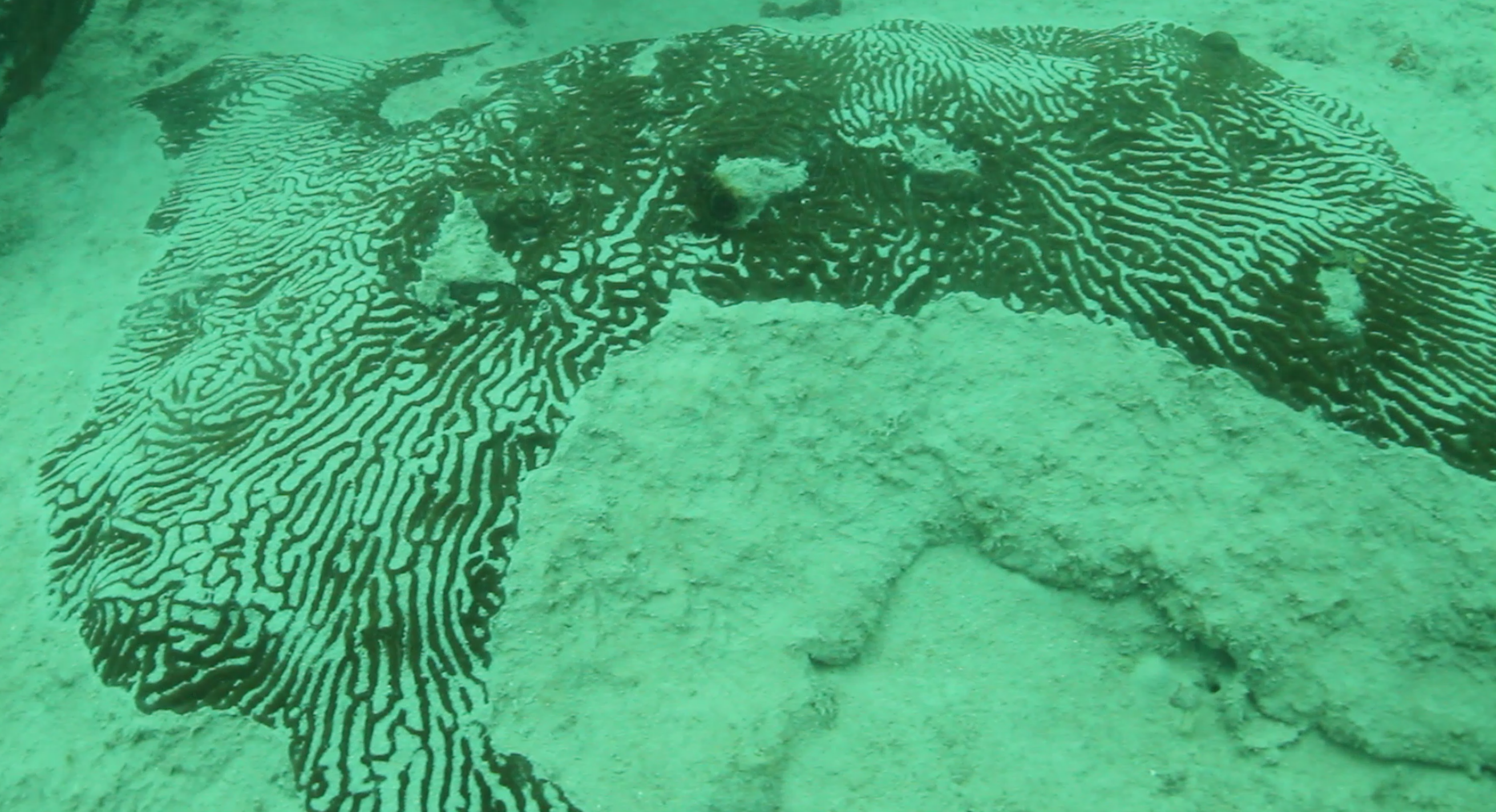

Eample of dredging impacts on corals in Miami. Photo: Evan D'alessandro, Ph.D.