When Josephine Caminos Oría, M.A. ’02, was in her early twenties, she rediscovered a part of herself that was at once deeply familiar and otherworldly. One of six children of Argentine immigrant parents, Oría grew up in Pittsburgh and was, in her words, “raised straddling two cultures.”

Outwardly, the family fully embraced life in the United States, but at home they were thoroughly Argentine. Annual trips to Buenos Aires and to her family’s ranch in the pampas of Santa Fé Province, as well as her grandparents’ regular sojourns to Pennsylvania, kept Oría connected to the country of her birth.

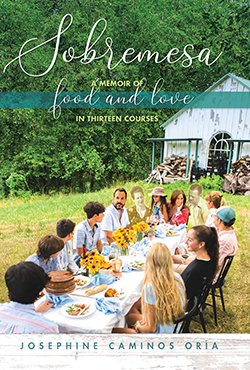

Their Argentine identity was particularly evident in the food the family ate and the mealtimes they shared. As Oría writes in the introduction to her new memoir, Sobremesa: A Memoir of Food and Love in 13 Courses, “we ate like Argentines,” especially in their faithful adherence to the tradition of sobremesa—a word that, as Oría points out, has no direct English translation.

“Sobremesa is the time you spend lingering at the table after the meal is done,” Oría explained. “It’s that time when, bellies full, you really just start sharing. It’s the communion of what you’ve just eaten together [and] the walls that separate us start coming down. And that’s when you take time to connect, whether it’s 15 minutes or two hours. Throughout most of Latin America, they call it the last ingredient.”

In Oría’s family, sobremesa was “non-negotiable;” nobody could leave the table before being formally excused. Conversation flowed—and people’s real selves came out. “It’s not always beautiful talk and nothing [was] off the table,” she said. “It could get heated, it could be funny, but everyone is allowed to be heard and seen no matter what they say. It could be somber—you could be remembering loved ones. Food is like a portal that brings out those who are no longer with us.”

In Sobremesa (the book), Oría summons the spirits of her mother, grandmother, and what she calls “the legion of ghosts and ancestors past who frequented my family’s dining room” to tell a story of growing up and living between two worlds and finding her true roots in the “in-between spaces.” And although primarily a memoir, the book’s 13 chapters each conclude with a recipe suffused with meaning and memories.

A life-changing journey

As she reached adulthood, Oría found herself at a crossroads. She had graduated from Duke University and medical school beckoned. Around this time a long-term relationship with her first boyfriend ended and Oría was devastated. Seeing her unhappiness, her parents strongly encouraged her to go to Argentina to help with the family’s cattle ranches. It was a life-changing journey.

“Going back to Argentina in my early 20s was something I never thought I would do,’” Oría said. “I had always gone every year, but I really discovered Argentina as a young adult. When you’re there for three weeks, vacationing, it’s different from being there for months on your own, exploring. I got a job there, and I fell in love with someone [now her husband, Gastón Oría] and it really helped me find that other side that I always thought I knew.”

She and Gastón married and began to build a family life of their own, eventually having five children. Along the way Oría built a career, at first in the finance sector in Argentina. When the Argentine economy teetered in the late 1990s, she and Gastón moved to Miami. She got a job as a news writer for a local television station and started a master’s program in broadcast journalism at the University of Miami.

“The program taught me to write so well,” Oría said. That said, her experience covering the September 11 attacks taught her “that I was stronger than I thought, [but it] takes a certain strength, a certain desire. I was too impacted,” she said. “After September 11, I decided to take a novel-writing class at the University of Miami, and I think I knew I was going to be a writer.”

Seven years later, Oría and her family were back in Pittsburgh, and she was working in the health care industry, eventually reaching C-level. Yet the mystical pull of family, sobremesa, and her Argentine roots proved irresistible.

“I was in my mid 30s, and I woke up one day with this insane desire to make dulce de leche,” she said, referring to the golden milk jam that is a pantry staple in Argentina and other Latin American countries. She called her maternal grandmother, María Dora “Dorita” Germain, to ask for the recipe that transported Oría back to her childhood, Argentina, and what she calls her “team of angels.” Dorita’s cooking was, Oría recalled, “amazing. My sisters and I would sit in the kitchen with her and cook, or just watch and learn through osmosis. She didn’t have recipes, but I can still hear her now.”

Thus started a quest to capture the alchemy of raw milk, sugar, heat, and time that yields proper dulce de leche, which in turn became a side venture, and then, in 2016, a full-time business. Oría and her husband make small-batch, artisanal dulce de leche, selling it online and in Pittsburgh-area supermarkets under the brand name La Dorita, in honor of her grandmother. A cookbook followed in 2017, as well as a kitchen incubator for aspiring specialty food makers and chefs, and a specialty food consulting business.

Oría and her family, who now make their home in South Carolina’s Low Country, worked to keep the mealtime traditions of their shared Argentine heritage going, and sometimes it was hard. “Our world at home centers around food,” she said. “[And although] my husband and I both work, and some of my kids were on two teams, and my 18-year-old would have plans, we would still try to have sobremesa, but sometimes we were just never around to have dinner during the week.”

“Then COVID hit and all that stopped, and we were doing it every night again—playing music for the kids, and they were playing their music for us, and sometimes we get up and dance around the table. It really centered us, and we’re not going back.”