MIAMI—In a new analysis on managed retreat—the climate adaptation response of moving people and property out of harm’s way—researchers explore what it would take for managed retreat to be supportive of people and their priorities. A key starting point is considering retreat alongside other responses like coastal armoring and not just as an option of last resort.

In a new paper in the journal Science, University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science researcher Katharine Mach argues that managed retreat should be viewed as a proactive option that can support communities and livelihoods in the face of climate change.

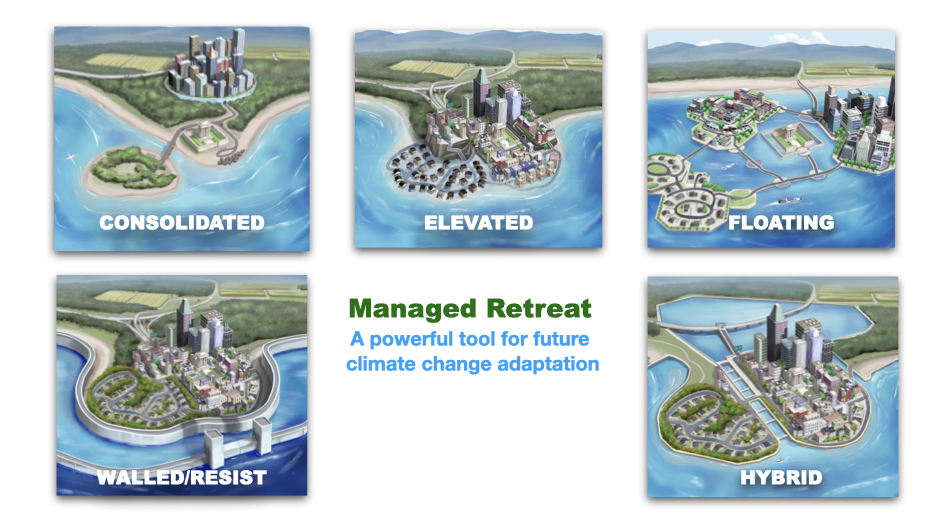

“Managed retreat can be more effective in reducing risk—in ways that are socially equitable and economically efficient—if it is a proactive component of climate-driven transformations,” said Mach, an associate professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at UM Rosenstiel School. “It can be used to address climate risks, along with other types of responses like building seawalls or limiting new development in hazard-prone regions.”

In the review paper, Mach and her colleague A.R. Siders from the University of Delaware reviewed the existing literature on the subject to argue that societies will be better prepared for intensifying climate change—such as more frequent and severe storms, flooding and sea-level-rise—if they consider the potential role of strategic and managed retreat.

“Communities, towns, cities and municipalities are making decisions now that affect the future,” said Siders, a core faculty member in UD’s Disaster Research Center and assistant professor in the Biden School of Public Policy and Administration and geography and spatial sciences. “If we’re making these decisions now, we should also be considering all the options on the table right now, not just the ones that keep people in place.”

Retreat is already happening in the U.S. and many parts of the world in the face of relatively moderate climate change and has happened throughout human history.

“Early conversations about managed retreat—and where, when, and why its use could be considered acceptable or not—substantially increase the likelihood that future climate retreat will promote societal goals,” said Mach.

In a related study in the Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, Mach and UM doctoral student Carolien Kraan conducted the first comprehensive overview of equity concerns that have been raised on voluntary property buyouts and provide policy options for addressing these concerns.

For example, they suggest that local governments involve residents in the buyout process from the start and provide homeowners with professional support to guide them through the process to reduce frustration.

“The article provides practitioners and researchers with a synthesis of policy options that are aimed at improving social justice outcomes in voluntary property buyout programs,” said Kraan, a doctoral student at the UM Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy.

The review paper, titled “Reframing strategic, managed retreat for transformative climate adaptation,” was published on June 18 in the journal Science.

The study, titled “Promoting equity in retreat through voluntary property buyout programs,” was published May 11 in the Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. The authors include Jennifer Niemann from the UM Rosenstiel School, A. R. Siders from the University of Delaware and Miyuki Hino from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Funding for both studies was provided by the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and the Leonard and Jayne Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy.