Ehsan Sheikholharam’s firm, ACFORM, has completed a seven-story commercial center at one the busiest intersections in the city of Mashhad, the second largest city in Iran. Sheikholharam is a part-time faculty member and alumnus of the University of Miami School of Architecture. He received his second masters from UMSoA in 2014 and is going to complete a Ph.D. in history and theory as well.

The site of the project is adjacent to the campus of the IAUM, the city’s major private university, with a student population of more than 25,000 students. The center includes high-end retail shops, restaurants and cafes, ballrooms, banks, and financial institutions. The first underground floor is exclusively dedicated to jewelry shops arranged in the fashion of Parisian passages and galleries. Beneath the galleries, two stories of intelligent parking garages descend 40 feet to the second and third underground levels. With a total of 160,000 square feet, the project provides fascinating services beyond the scale of its immediate neighborhood.

The 27,000 sq. ft. site is situated at a wide intersection upon which the urban code imposes a very large corner chamfer, or sort of beveled edge. The resulting irregular geometry, originally thought to be an obstacle, was indeed the main inspiration for the design.

“The idea is very simple,” Sheikholharam said. “The wide angles of visibility offered by the relatively open intersection, as well as the mandatory chamfer at the corner suggested that instead of designing two separate facades, we could design a single facade folded around the corner. I heard the site and did exactly that. I awakened the site’s unconscious.”

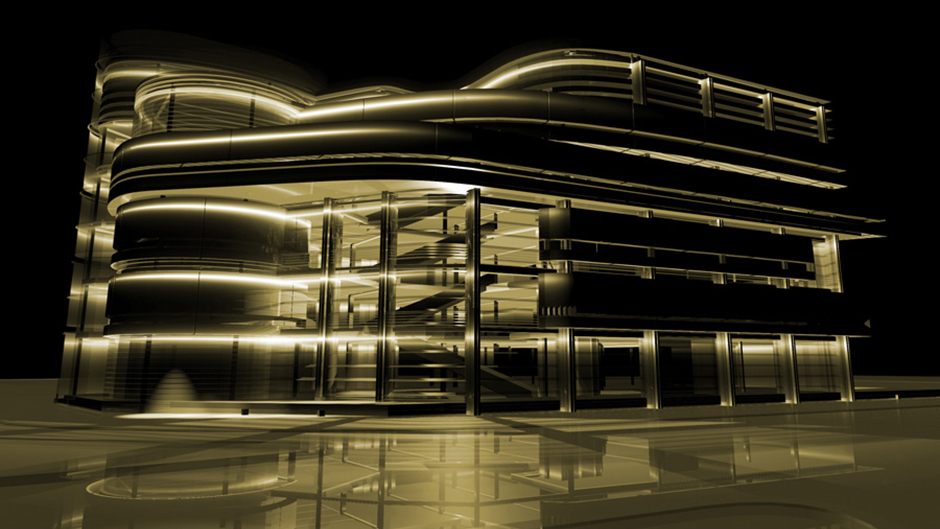

The facade deploys a series of horizontal bars balanced by vertical geometric shapes — an extruded ellipse anchoring the end of the site and a cylinder turning the corner. The horizontal surfaces sporadically stretch and slide at different points to generate the intended sense of movement and energy, but also to distinguish the corner’s turning points. These movements spin around the vertical shaft to emphasize the entrance where the curtain wall and the cylinder meet.

In contrast to the white composite coating of the horizontal bars, which determines the overall shape of the building, the dark-hued curtains and the seamlessly horizontal louvers act as visual voids, enabling the facade to both dissolve into the sky and connect with the ground. The triangular plane at the very northern end and the diagonally opposite extruded ellipse mark the two very end corners, articulating the building from its immediate context.

The interior follows the same logic. Instead of confusing the project with multiple openings, all the energy is focused around a single central space. Ironically, the central atrium is not at the geometrical center; rather it is pulled to the edge of the building, next to the entry. Instead of trapping all of the excitements at the center of the building surrounded by shops, the central space opens up above the entrance, and more importantly to the city as well. The atrium is not purely decorative; the main circulations, escalators and elevators are integrated into it so that is functional as well.

The atrium, nevertheless, is a mathematical solution to the setbacks and the mandatory decrease of square footage required by municipal code. As opposed to simply forcing the building to step back in order to comply with the code, the atrium expands itself upward and offers dynamic views while compensating for the area reductions.

“When I left the country in 2012, OXIN was half-built. It was impossible to realize a 160,000 sq. ft. building without perpetual onsite surveillance and inevitable adjustments in design,” Sheikholharam said. “I would like to acknowledge the invaluable efforts of my dear colleague, Jafar Erabi, as well as the insightfulness of our client, Reza Sartaee, whose relentless contributions made this possible.”