Barely 10 minutes after blowing three deep breaths into a little tube, University of Miami sophomore Allegra Garcia heard the words about her coronavirus test that would give her peace of mind: “You’re clear.”

“I think this is way better than the nasal swab because you know right away,” said Garcia, one of hundreds of University upper-class students who this week began a new routine of taking twice-a-week breath tests to detect COVID-19. “Imagine all those people you could interact with before you’d get your swab results in a day or two. They are potentially at risk because you didn’t know you had it.”

Eliminating that risk is a big reason why the University is among the first in the nation to employ the COVID-19 Breath Analyzer in its arsenal aimed at halting transmission of the highly contagious virus. Erin Kobetz, vice provost for research and scholarship, explained that any student who gets a “Not Clear” on the breath test developed by the Israeli-based TeraGroup will take a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nasal swab test, and isolate quicker.

“The breath test is an innovative tool that allows for close to real-time detection of COVID, and there is power in knowing now,” said Kobetz, who took the breath test on Monday to see how it works. “It literally took two minutes from the time I blew into the tube until the time that I had results. The benefit of this technology is the rapidity by which the results are produced, allowing for a sort of point-of-care response that is ultimately the best strategy for preventing further transmission of infection.”

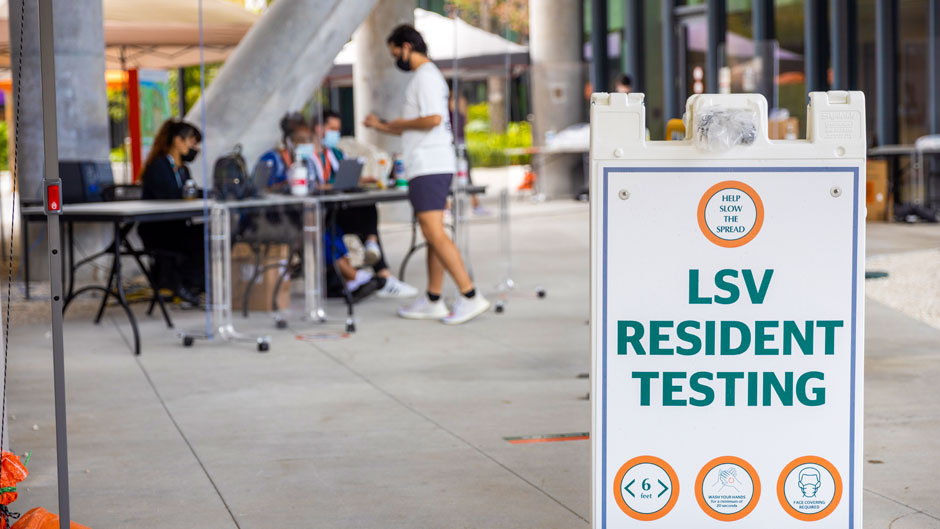

For now, only students at Lakeside Village and University Village have shifted from the required once-a-week PCR nasal swab to the twice-a-week breath tests. But, Kobetz said, their experiences will help the University decide whether it’s feasible to expand the use of the breath analyzers.

“We may expand beyond these groups, but we wanted to start with a smaller universe of students to get it right,” she said. “This is more of an extended feasibility study, where we can collect some lessons learned from the rollout and consider if it is a strategy that should be offered to the University at large.”

She noted that students in the upper-class residential villages were chosen for the feasibility study for a couple of reasons. First, many student there already volunteered to take the breath tests last year when the University became the first college testing site for the breath analyzer, with the goal of providing TeraGroup and its U.S. subsidiary BioSafety Technologies the data needed to seek emergency use authorization for the new technology from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the use of the breath analyzer as an aid in ongoing surveillance mechanisms on campus, and the FDA is still evaluating the emergency use authorization.

Another reason, Kobetz said, is both villages had the adequate space available needed to accommodate the breath machines and the teams of people needed to supervise the tests.

While some students who arrived at Lakeside Village for their pre-scheduled appointments on Monday had to wait a bit longer for their results than Kobetz did, they agreed that the breath test is—as Dr. Roy E. Weiss, the University’s chief medical officer for COVID-19, has said—as simple as blowing into a kazoo.

After checking in at a reception desk near the village’s Music Practice Room, students were directed to one of three test stations in the open space. There, an observer gave each student the small disposable, sterile TeraTube. They each were directed to open it, blow three deep puffs into it and then close it.

From there, each tube was whisked to the nearby music room, where a research assistant inserted it into a freestanding BioSafety Station that, within a minute, usually detected no trace of COVID-19 in the droplets of breath. Soon after, the results were delivered back to the check-in desk, where a UScreen team member gave each waiting student the words: “Clear” or “Not clear.”

“It was no big deal,” said senior Mark Oliger, a computer science major, who like Garcia, appreciated the logic behind having near-instant results. “I think the big benefit is it will slow the spread, and it’s good that they’re making it easy for us to do our part to meet that goal.”