Almost half of those who die globally, nearly 26 million people, including over 2.5 million children, have serious physical or psychological suffering and need palliative care and pain relief.

Globally, some 61 million people suffer serious physical and psychological suffering and pain each year. Of this total, some 83 percent live in low- and middle-income countries where access to low-cost, off-patent morphine is rare or completely unavailable, even though the cost should be pennies a tablet.

The annual burden in days of severe physical and psychological suffering is huge - six billion days worldwide, 80 percent in the low- and middle-income countries, according to The Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief, which studied this health issue for three years. This major report is now available in The Lancet, published October 12.

Of the 298.5 metric tons of opioids in morphine distributed worldwide, only 10.8 metric tons (3.6%) is distributed in low- and middle-income countries, and only 0.1 metric ton (0.03%) is distributed to low-income countries.

“The pain gap is a massive global health emergency which has been ignored, except in rich countries,” said Felicia Marie Knaul, Ph.D., chair of The Lancet Commission, professor of public health sciences at the Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami and director of the University’s Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas.

“This global pain crisis can be remedied quickly and effectively. We have the right tools and knowledge and the cost of the solution is minimal. Denying this intervention is a moral failing, especially for children and patients at the end of life,” she added.

Spearheaded by faculty at the University of Miami and Harvard University, The Lancet Commission’s analysis for the first time quantifies the massive scope of the global pain crisis. To address the problem, the commission calls for an essential package of palliative care to be made available by health systems worldwide. At the center of the essential package is immediate release, oral and injectable morphine. In high-income countries, a pain-relieving dose costs 3 cents per 10 mg. In low-income nations, the same morphine cost 16 cents where and when it is available.

“If low- and middle-income countries could obtain morphine at the same price as rich countries, the annual global price tag for closing the gap in access to morphine would be $145 million, a fraction of the cost of running a medium-sized U.S. hospital,” said Knaul, who brought the Commission to UM after its start at the Harvard Global Equity Initiative.

“This is a pittance compared to $100 billion a year that the world’s governments spend on enforcing global prohibition of drug use,” Knaul continued. “The biggest shame is children in low-income countries dying in pain which could be eliminated for $1 million a year.”

“No health system can expect to meet the needs of its people without providing access to basic pain relief and palliative care,” said Paul Farmer, M.D., Ph.D., co-chair of The Lancet Commission and professor at Harvard Medical School. “What we have here is an access abyss of palliative and pain relief for the poor,” he said. Farmer is also a co-founder of Partners in Health, which runs a hospital in Haiti and projects in Africa, South America, Mexico and Russia.

Lack of money is only part of the problem, according to Jim Yong Kim, M.D., Ph.D., President of the World Bank. “Failure of health systems in poor countries is a major reason that patients need palliative care in the first place,” said Dr. Kim, a co-founder of Partners in Health and former Harvard professor. “More than 90 percent of these child deaths are from avoidable causes. We can and will change both these dire situations.”

Where the pain crisis is most severe

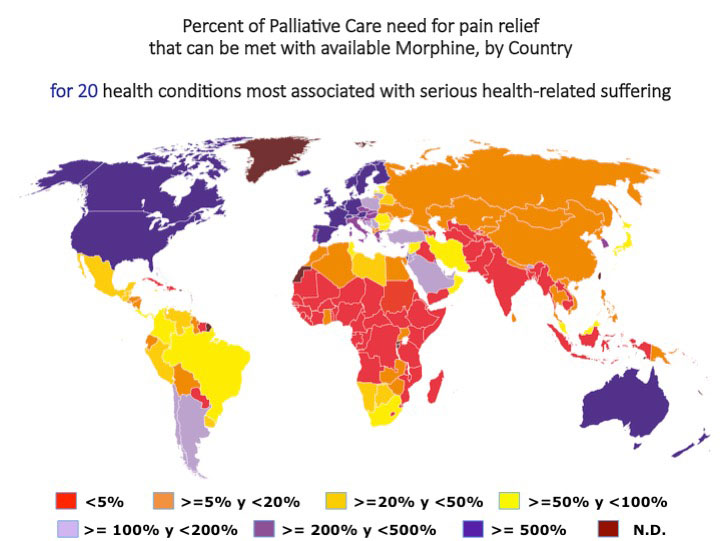

In the most comprehensive global analysis of palliative care ever conducted, The Lancet Commission of 35 experts measured the need for palliative care in 172 countries, caused by 20 life-threatening and life limiting diseases such as HIV, cancers, heart disease, premature birth, tuberculosis, hemorrhagic fevers, lung and liver disease, malnutrition, dementia and trauma injuries.

“The results are startling,” said Julio Frenk, M.D, Ph.D., a senior author of the report and President of the University of Miami. “The pain gap is a double-edged sword with too little access to inexpensive opioids for poor nations and misuse by the rich ones. The enormous disparity between need and availability of opioids for palliative care is growing and skewed against people living in poverty.”

Out of the 172 countries studied, 25 nations provided had almost no morphine and therefore could not provide standard palliative care to their population with severe health-related suffering. Another 15 countries distributed enough opioid analgesic to attend to less than one percent of those needing pain relief. In total, 100 countries had only enough to meet the needs for standard pain relief for less than 30 percent of their patients. More than 75 percent of the world’s population lives in countries that provide less than half of the morphine needed for palliative care.

The major problem is in eight of the countries with the largest global populations. China has enough opioid analgesic to meet the needs of only 16 percent of those needing pain relief; India-4.0 percent; Indonesia-4.2 percent; Pakistan-1.5 percent; Nigeria-0.2 percent; Bangladesh-3.9 percent; Russia-8.0 percent; and Mexico-36.0 percent. Brazil has enough for almost 75 percent who need it. Among the 10 most populous nations, only the United States has the opposite problem – an opioid epidemic.

Barriers to palliative care

Low- and middle-income countries are paying much more than they should have to for morphine – 16 cents per 10 mg tablet, compared to three cents in high-income countries. To bring the price of morphine in line globally, low- and middle-income governments need to negotiate prices with the main producers of low-cost morphine.

Governments need to adopt policies and laws that maximize access and standardize best world prices for morphine for palliative care and other medical needs. Countries need the support of a global medicines financing facility that must be led by an international financial institution such as the World Bank that must also include medicines for treatment.

To date, the focus and funding has gone toward preventing the non-medical use of internationally controlled substances, like opioids. For the most part, this has crippled access without balancing the human right to access these medicines to relieve pain and suffering.

“To complement policies to increase medical access, safeguards must to be put in place to ensure that morphine is not diverted for non-medical use,” said Knaul. “This is doable. Case studies in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Uganda and Kerala, India demonstrate that increased access for medical purposes can be achieved safely.”

Another barrier is the focus by physicians and global health advocates on cures and extending life and neglecting care giving, especially at the end of life.

“Prejudice and misinformation about the appropriate medical use of opioids are common among those in severe pain and their family members,” explained Kathy Foley, M.D., senior co-author and former Chief, Pain and Palliative Care Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

About the Report

The report is wide-ranging and detailed so that it can be used by ministries of health and other policy makers, physicians, hospital administrators, clinic managers, care givers and researchers and medical schools.

The work by 35 experts and 26 collaborating researchers from 25 countries, spearheaded by the University of Miami and Harvard University, covers how to integrate palliative care into health systems of low- and middle-income countries, a full list of items for an essential palliative care package and calls for all medical personal to have training as palliative caregivers.

“To improve the usefulness of the report, we used case studies and examples how individual countries overcame individual problems,” said Lukas Radbruch, M.D., Ph.D., a senior co-author of the report and Chair of Palliative Medicine at the University of Bonn, Director of the Palliative Department at Bonn University Hospital and Chair of the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care.

Financing

“For most countries, public financing that is integrated into all national insurance and social security programs are crucial to cover palliative care,” said Dr. Frenk. “The package of services must cover the cost of the essential palliative care package at district hospitals, primary care clinics and some services at the household level.”

In Mexico’s Seguro Popular, palliative care has been integrated into the Fund for Personal Health Services, which covers care in general hospitals and clinics.

In Chile, palliative care has been included in the package of Explicit Health Guarantees to cover patients with cancer.

Access to palliative care and pain relief is an essential component of universal health coverage and achieving the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals.

“I have experienced the pain of cancer,” said Knaul. “I have accompanied a loved one dying in the pain of cancer. No human being should go through this without pain medicine. We can ensure that the 61 million people a year who need it get palliative care. The alternative is unacceptable and unthinkable.”

SOURCE: The Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief