For now, El Niño is the big question. What effect will it have on the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season? Anyone who has had a taste of the destructive and costly storms that have pummeled Florida and the Caribbean the past two seasons certainly wants to know.

The climate phenomenon, in which ocean surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific become warmer than normal, can actually trigger an increase in vertical wind shear over the Caribbean and Atlantic, suppressing tropical cyclone development.

“We’ve been in an ongoing El Niño for a while now,” said Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “And current forecasts have it holding out through early fall.”

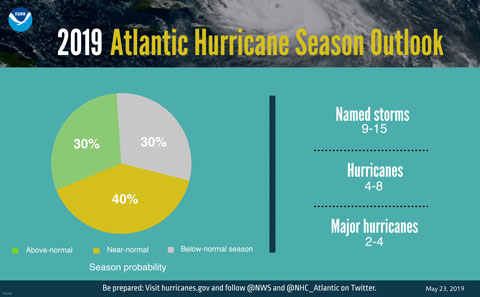

When the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued its outlook for the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season last week, El Niño was one of the factors the agency used to help shape its forecast.

“El Niño is a huge phenomenon, and it disrupts weather patterns around the globe,” said Kirtman. Director of NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies based at the Rosenstiel School, Kirtman led a team of scientists in developing an El Niño/La Niña prediction system—the North American Multi-Model Ensemble—that helps improve El Niñoforecasts and provides data used by NOAA in its seasonal hurricane outlook. (La Niña episodes represent periods of below-average sea surface temperatures across the east-central equatorial Pacific.)

For 2019, NOAA has predicted a “near-normal” season, with nine to 15 named storms, four to eight of which could become hurricanes, including two to four major hurricanes of Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale.

For 2019, NOAA has predicted a “near-normal” season, with nine to 15 named storms, four to eight of which could become hurricanes, including two to four major hurricanes of Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale.

The season runs from June 1 to Nov. 30 and peaks in August and September. One named storm, Andrea, formed 11 days before the season’s official start, making it the fifth year in a row that the season got off to any early start. Andrea fizzled a day after it formed.

While El Niño is expected to suppress the intensity of the season, a number of competing factors are at play that could counter its effect, among them warmer-than-average sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea and an enhanced west African monsoon, both of which favor increased hurricane activity.

“There is still a lot of randomness, so even in an El Niño year there can be active seasons in the Atlantic,” said Amy Clement, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School. “It’s important to remember that therewill be hurricanes, and some will make landfall—and it takes only one to have a major impact.”

Which is why residents of the coastal United States should always be at the ready, cautioned Matthew Shpiner, director of emergency management at UM. “The unfortunate reality is that we live in one of the most hurricane-prone areas in the country, and with hurricane season starting Saturday, it is critical that the University community be prepared,” said Shpiner, noting that NOAA’s outlook is for overall seasonal activity and not a landfall forecast.

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center will update the 2019 Atlantic seasonal outlook in August just prior to the historical peak of the season.