MIAMI—A new study led by researchers at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and at the Institute of Marine Research in Norway found that European glass eels use their magnetic sense to “imprint” a memory of the direction of water currents in the estuary where they become juveniles. This is the first direct evidence that a species of fish uses its internal magnetic compass to form a memory of current direction.

“It’s an important step forward in understanding the migratory behavior of the commercially important European eel and in expanding our knowledge of the orientation mechanisms that fish use to migrate,” said Alessandro Cresci, a Ph.D. student at the UM Rosenstiel School and first author of the paper. “This research should provide awareness that tiny young eels can accomplish incredible tasks to migrate.”

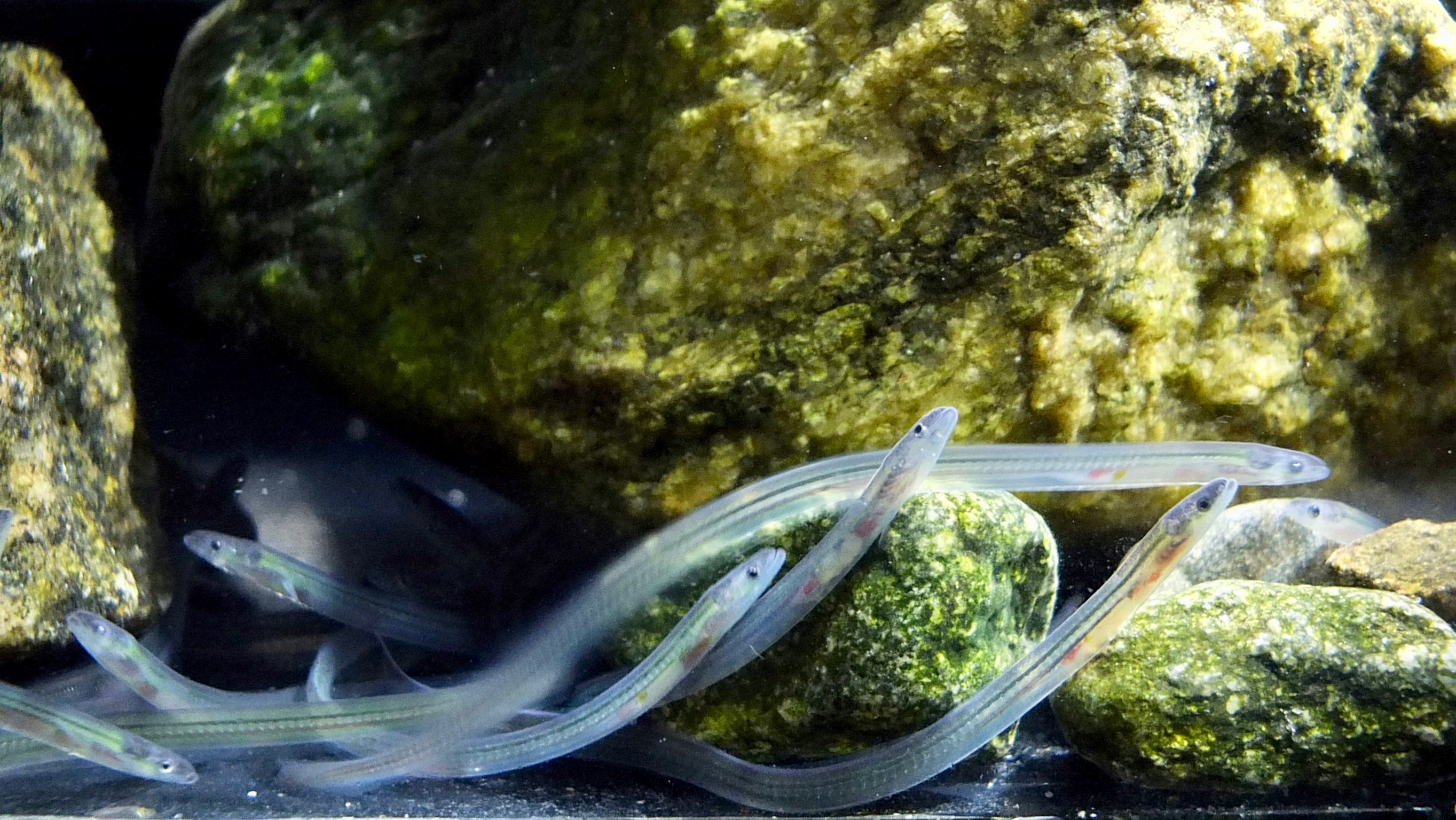

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is a migratory species that crosses the Atlantic Ocean twice during its life. After hatching in the Sargasso Sea, eel larvae move more than 5,000 kilometers with the Gulf Stream until reaching the continental slope of Europe. There, they metamorphose into the post-larval transparent glass eel and continue the migration across the continental shelf to the coast. After reaching the coast, glass eels enter estuaries, where some of them continue their migration upstream into freshwater until later in life (up to 50 years), when as silver eels, they navigate back to the Sargasso Sea to spawn and die.

The research team collected over 200 glass eels from various estuaries in the archipelago of Austevoll, Norway flowing in different directions: north, south, southeast or northwest. The fish were then placed in a magnetic laboratory, the "MagLab," where magnetic north was rotated to observe their magnetic orientation . In each case the eels oriented towards the magnetic direction of the prevailing tidal current occurring at their recruitment estuary at the time of the tests.

The findings show that glass eels use their magnetic compass to memorize the magnetic direction of tidal flows in their recruitment estuary, which may help them orient in moving water during migration.

“Surprisingly, fish early life behavior can be goal oriented.” said Claire Paris, professor of ocean sciences at the UM Rosenstiel School. “This study complements previous findings showing innate magnetic sense in glass eels and highlights the importance of understanding the complexities of larval behavior. There is a lot we need to learn”.

The European eel is a commercially important species that is critically endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Eel populations have declined precipitously since the 1980.

The study, titled “Glass eels (Anguilla anguilla) imprint the magnetic direction of tidal currents from their juvenile estuaries,” was published October 8, 2019 in the journal Nature Communications Biology. The study’s authors include Alessandro Cresci and Claire Paris from the UM Rosenstiel School; Caroline Durif, Anne-Berit Skiftesvik, and Howard Browman from the Institute of Marine Research’s Austevoll Research Station; and Steven Shema from Grótti ehf in Iceland.

The research was supported by the Paris Lab at the UM Rosenstiel School by a grant from U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF-OCE 1459156) the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (project # 81529) and by the Research Council of Norway (project # 234338).