MIAMI—A new study from oceanographers at NOAA and the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) has for the first time described the daily variability of the circulation of key deep currents in the South Atlantic Ocean. The research by the lead CIMAS scientists based at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) demonstrates strong variations in these key currents, changes that are linked to climate and weather around the globe.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, found that the circulation patterns in the upper and deeper layers of the South Atlantic often vary independently of each other, an important new result about the broader Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) in the Atlantic.

“A key finding from this study is that our data showed that the ocean currents in the deepest parts of the South Atlantic Ocean behave differently than we thought before we had this new long-term dataset, which may have large implications for the climate and weather forecasts made by ocean models in the future,” said Marion Kersale, an oceanographer with the UM Rosenstiel School's Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies and lead author on the study.

The MOC is one of the main components of ocean circulation, which constantly moves heat, salt, carbon, and nutrients throughout the global oceans. Variations of the MOC have important impacts on many global scale climate phenomena such as sea level changes, extreme weather, and precipitation patterns.

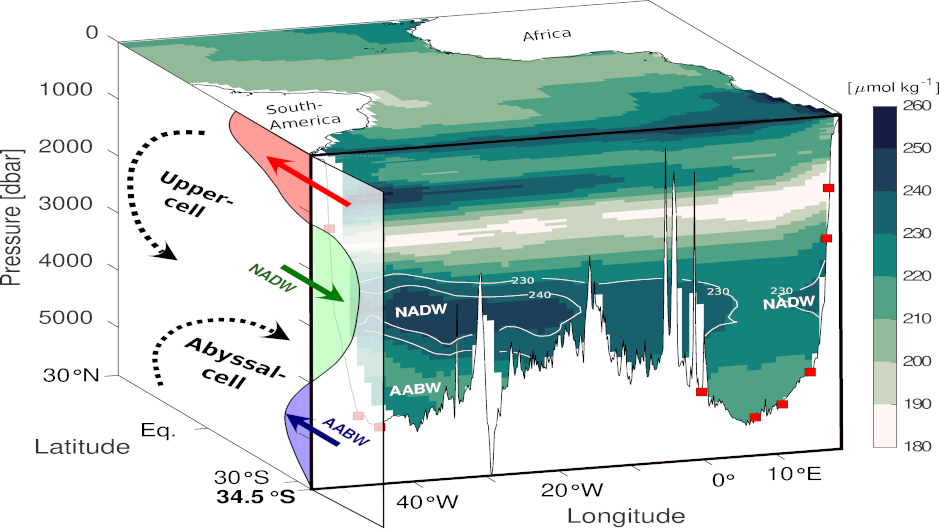

The MOC consists of an upper cell of warmer, lighter waters that sits on top of colder, denser waters, known as the abyssal cell. These water masses travel around the global ocean, exchanging temperature, salinity, carbon and nutrients along the way.

This study provided remarkable insights into the full-depth vertical, horizontal, and temporal resolution of the MOC. A key new result from this study has been the estimation of the strength of the abyssal cell (from 3000 m to the seafloor), which previously have only been available as once-a-decade snapshot estimates from trans-basin ship sections.

This study found that the upper layer circulation is more energetic than that in the very deep, or abyssal, layer at all time scales ranging from a few days to a year. The flows in the upper and deep layers of the ocean behave independently of one another which can impact how the entire MOC system influences sea level rise and hurricane intensification in the Atlantic.

Research such as the study led by Kersale is helping oceanographers to refine and improve our understanding of the complexities of the MOC system. These observations will allow scientists to validate Earth system models and will aid in UM Rosenstiel School and NOAA’s goals to improve our understanding of the climate/weather system.