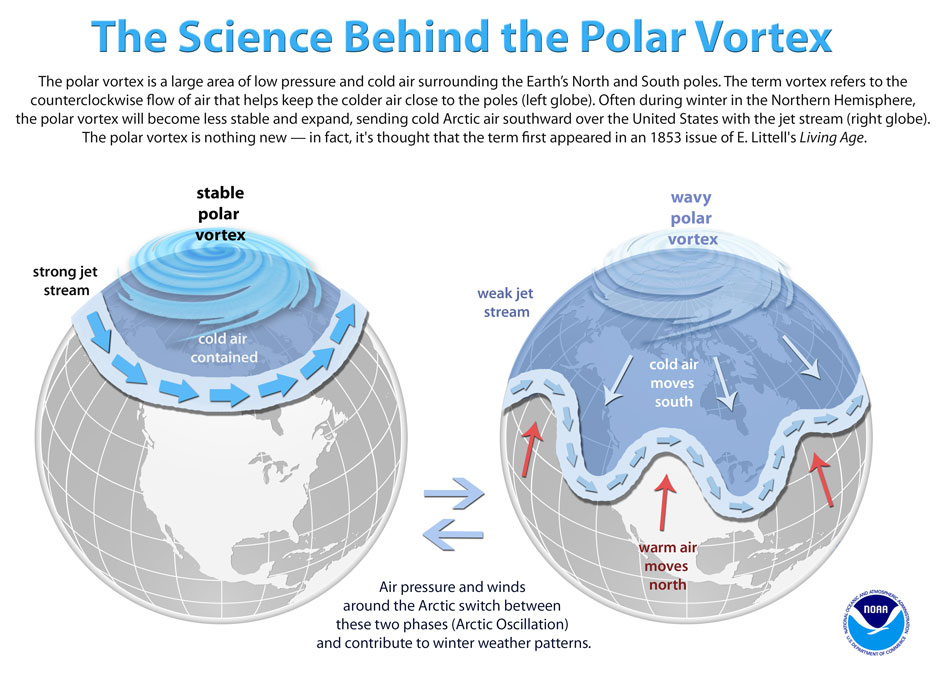

The team of scientists started issuing the forecasts back in mid-January, warning that a break down in the polar vortex—the massive area of cold air spinning high in the atmosphere above the Arctic—would occur in the next three to four weeks.

Then, a month later, a blast of ultra-cold air from Canada brought the season’s harshest weather to the central United States, knocking out power to millions of people in multiple states and claiming dozens of lives from southern Texas to northern Ohio.

Could lives and critical infrastructure been saved had operators heeded warnings and started making preparations well in advance? That is a question now being hotly debated.

But what is clear is that a multi-institutional, long-range forecast project developed by a University of Miami atmospheric scientist accurately predicted weeks in advance the breakdown of the polar vortex that brought the big freeze to many parts of the U.S., with the Lone Star State being hardest hit.

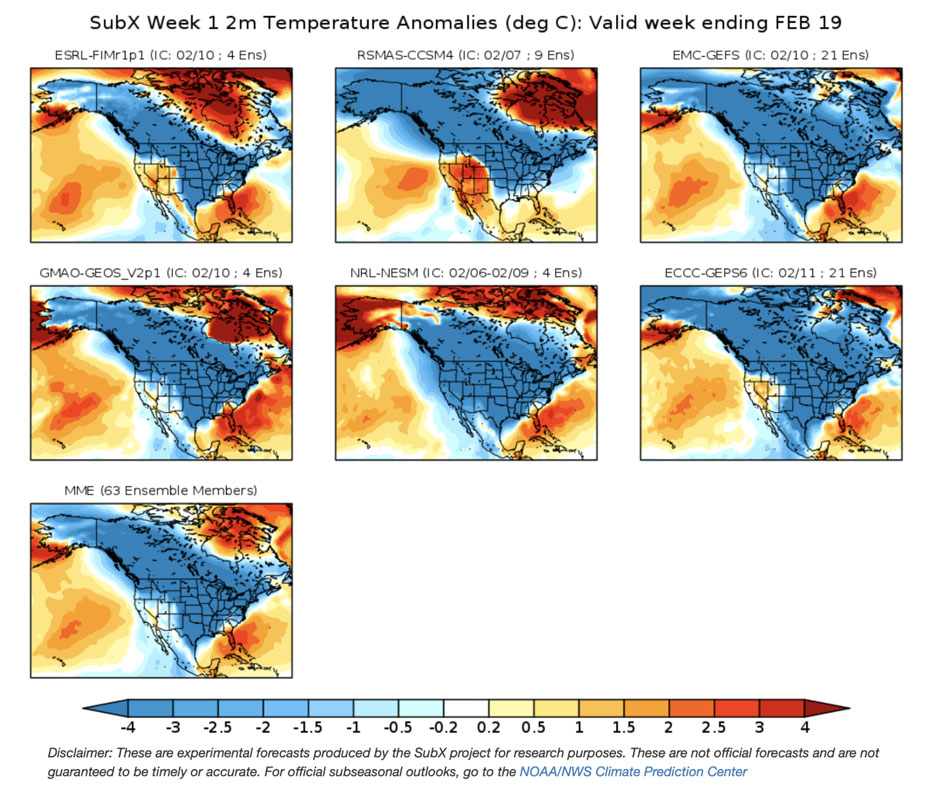

That project, the Subseasonal Experiment, or SubX for short, combines multiple global models from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA, Environment Canada, the Navy, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and others to forecast weather conditions three to four weeks ahead.

“The diversity of tools—in this case, multiple forecasts—is critical,” explained Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and the chief architect of SubX. “Just like the diversity of ideas in an institution is important to come up with the best solution, the diversity of prediction tools is important here because any one model has biases,” he said. “If we had used only one tool that wasn’t very good at predicting the breakdown of the polar vortex, we would have missed accurately forecasting this event.”

Five of the six models used by SubX predicted the breakdown, with the model powered by the Rosenstiel School being the most accurate, said Kirtman, who is also director of the University of Miami-NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS). “Our model was the most bullish,” he said. “One of the models said no. So, the probability was five out of six that we were going to see this breakdown.”

According to Kirtman, a probabilistic forecast is needed in climate and weather prediction. “You want to include the chance that you might be wrong, and the best way to explore a realistic assessment of the range of possible outcomes is to use this multi-model/multi-ensemble approach,” he said.

In addition to atmospheric data, SubX models also factor in oceanic conditions. “In the past, we haven’t done that,” Kirtman noted..

Supercomputers are the pillars of SubX, said Kirtman, noting that the supercomputer at the University of Miami Institute for Data Science and Computing powers the Rosenstiel School model that forecast the polar vortex breakdown.

The origins of SubX date back to the late 1990s, when Kirtman, working for a nonprofit that conducted climate research, teamed up with a group of other scientists to figure out how to more accurately predict El Niño, a climate pattern associated with the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific and which can affect weather all over the world. “We found that by combining different forecasts we could produce the most reliable results,” he recalled.

SubX can help emergency managers and utilities prepare for natural disasters, like the brutal winter storm that devastated Texas, giving them the lead time to stockpile energy and prepare backup power systems, Kirtman said.

The responsibility must be shared, he said. “We have to develop a track record so that people trust the forecasts,” Kirtman added, “but then people also have to use those forecasts to make decisions.”

Already, there are certain entities that are using SubX data in their decision-making process, Kirtman pointed out, noting the U.S. Air Force. “But there is a certain amount of pressure on the SubX Team to start to seek out people who are interested in using it,” he said. It is a difficult process, requiring time to develop that kind of interaction, he noted. But his team seems to be winning over constituents, because SubX has been remarkably accurate in forecasting other weather events weeks in advance.

So, will battered Texas—which has been hardest hit by the harsh winter storms—catch a break from the weather? “Texas is going to see a little bit of a break, but not a huge one,” Kirtman said. “It’ll warm up some. But if you take a path northeast, through the Great Lakes region, you’re going to see some persistent cold temperatures three to four weeks from now.”

That could prove detrimental for some residents. While the frigid weather has disrupted COVID-19 vaccine distribution in several states, the freezing temperatures are also likely having an adverse impact on human health, according to Naresh Kumar, a Miller School of Medicine public health scientist.

“Hypothermia is the most obvious health effect,” said Kumar, associate professor of environmental health. “The cold exposure is also likely to trigger a cascade of other dangerous health effects, including a dramatic change in thermoregulation and constriction of airways, which in turn is likely to exacerbate pulmonary diseases such as COPD and asthma.”

One burning question: Are the sub-zero temperatures in any way related to climate change? “The current outbreak of extreme cold weather in the U.S. is probably not directly linked to climate change,” said Emily Becker, associate director of CIMAS. “Recent scientific studies have found that the warming Arctic is likely not connected to extreme cold in the mid-latitudes. There are a number of different climate patterns in play here, including La Niña and a negative Arctic Oscillation, that helped set the stage for this extreme weather event.”