Two University of Miami professors have been awarded a collaborative grant from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to study atmospheric particle formation in the Southeast region. “Our goal is to better understand how aerosols interact with cloud systems and affect the regional climate,” said Yang Wang, Ph.D., assistant professor of chemical, environmental, and materials engineering in the College of Engineering.

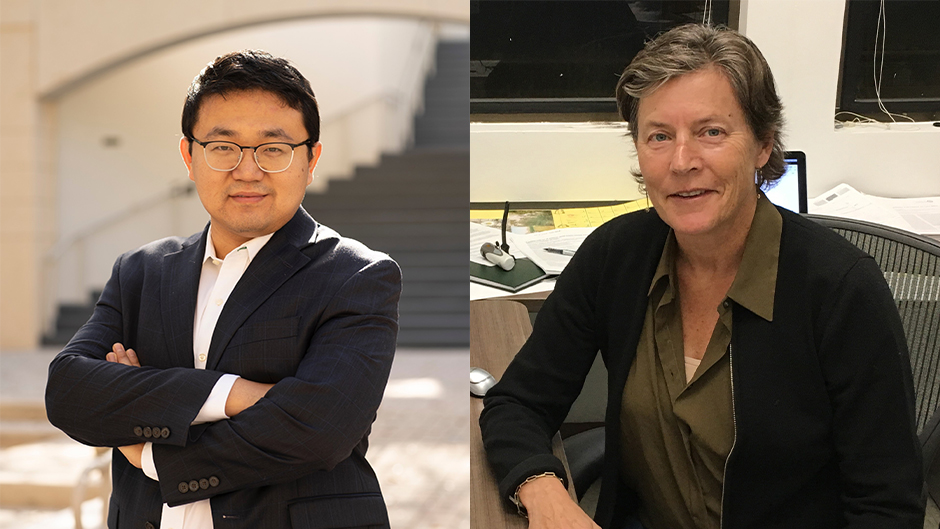

Wang is the principal investigator of the federal grant, “Interactions Between the Boundary Layer New Particle Formation and Cloud Systems,” with co-principal investigator Paquita Zuidema, Ph.D., professor and chair of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

“Our university was chosen because we have two very strong, complementary programs,” said Wang, noting that the grant was one of 24 new DOE projects totaling $15.3 million aimed at improving the power of Earth system models to predict weather and climate. “These grants will ensure a strong environmental and atmospheric sciences research program and expand the robust scientific workforce of our country, which will lead to important new insights into the nature of Earth system variability and change.”

A member of the Center of Aerosol Science and Technology (CAST) with faculty from the College of Engineering, the Rosenstiel School, and the Miller School of Medicine, Wang has focused his research on aerosols below 10 nanometers, which can form when gas molecules interact and gradually increase in size– a process called new particle formation (NPF). “These particles can become cloud droplets that potentially lead to precipitation,” said Wang. “However, the formation of clouds blocks solar energy that gaseous molecules need to form particles.”

New particle formation is receiving a lot of attention right now because the processes are still open to debate, said Zuidema. “This project is unique by focusing on how clouds can encourage NPF, rather than the other way. The basic idea is that when rain cleans out the air and reduces cloud cover, more sunlight can reach near the surface and that energy can encourage the formation of more particles.”

Zuidema added that the newly formed particles can also impact cloud characteristics, primarily through reducing the droplet size. That would increase cloud reflectivity, and delay precipitation, which increases cloud lifetime with potential long-term implications for a changing climate.

Wang and Zuidema said the Southeastern U.S. is an ideal location for studying these atmospheric interactions, as cold fronts from the north can deplete local pollution and cloud cover during the winter months. In addition, the region’s pine forests emit many volatile gases that can easily be converted to new particles. “The pine forests are representative of the entire region, including the Everglades near Miami, and the findings have global relevance,” said Zuidema.

She added that the DOE is deploying a sophisticated instrument suite near Huntsville, Alabama, to collect a range of new measurements over several years. “This project relies on good meteorological measurements, such as tethered balloons that can determine if NPF occurs near the ground or higher in the atmosphere,” said Zuidema. “Measurements across the full 24-hour cycle will help determine the relationship to sunlight for NPF.”

Wang said two UM doctoral students will participate in the new research project. “They will learn the fundamentals of aerosol transport and monitoring, work with the DOE’s advanced instrumentation, and gain an understanding of atmospheric science,” he said. “It’s a great opportunity for hands-on learning, while advancing our knowledge of aerosol processes.”