Three interdisciplinary teams have been awarded the first Phase II grants from the UM Laboratory for Integrative Knowledge (U-LINK) for research projects that, one day, could make a difference in the lives of millions of Floridians facing increasing threats from hurricanes, sea-level rise, and harmful algal blooms and other marine pathogens.

The teams, which were judged by external experts and the U-LINK action team to have developed both great cohesion as multidisciplinary collaborators and promising ideas for resolving a pressing societal problem during their initial phase of funding, were each awarded $150,000 to advance their research. They were among the five teams that received U-LINK’s inaugural Phase I grants, which are designed to help members develop into cohesive teams, forgea shared vision, and refine their approach to their topic.

“Most universities assume that it’s enough just to offer money to interdisciplinary teams and watch them do their work,” said Susan Morgan, associate vice provost for research development and strategy, who along with Vice Provost for Research John Bixby, U-LINK’s accountable lead, oversees the U-LINK initiative. “U-LINK is different because we recognize that the process of creating a shared understanding of a big problem is itself hard. We’ve tried to give our U-LINK teams the support and the tools they need to think big while laying the foundation for the real work to come.”

Culled from 13 applications, the winners of U-LINK’s second round of initial development grants of $40,000 will be announced at the end of November.

The winning proposals and teams for U-LINK’s inaugural Phase II grants, which could be renewed for another $150,000 next year, are:

Aerosolization of algal toxins and pathogens in South Florida and their human health effects

For this project, team members from the Miller School of Medicine, the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, and the College of Engineering will use South Florida as a test case to investigate the risks posed to people who inhale toxic aerosols from breaking waves on the beach. They spent this past summer investigating the production of particles released into the air by harmful algal blooms (HAB) of cyanobacteria, commonly known as blue-green algae, and elevated bacteria levels in South Florida’s coastlines and waterways.

To date, almost all research on HABs and pathogens, which are a worldwide problem often triggered by agriculture fertilizer and sewage washing into waterways, has focused on human contact with them while swimming or consuming seafood. UM’s experts hope to fill the gap in knowledge about the ability of toxins produced by blue-green algae and marine pathogens to become airborne, inhalable particles.

“This research is especially timely as several impacts of climate change, including increased nutrient run-off, sea-level rise, and increased risk due to storm surge, are all predicted to increase both marine pathogens and harmful algal blooms in South Florida,” the team led by Cassandra Gaston,assistant professor of atmospheric sciencesat the Rosenstiel School, wrote in their application.

In this phase of their research, the team, which added new collaborators to its initial group, will conduct field studies to test HAB exposure levels in different communities and controlled experiments on the sea-to-air transfer of marine toxins and pathogens, and their toxic effects in a Drosophila animal model, in the Rosenstiel School’s SUrge-STructure-Atmosphere INteraction, or SUSTAIN, facility, which can simulate winds and waves.

In addition to Gaston, the co-principal investigators (PIs) on the project are: the Miller School’s Alberto Caban-Martinez, assistant professor, David Lee, professor, both in public health sciences, and Grace Zhai, associate professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology; and the Rosenstiel School’s Larry Brand, professor of marine biology and ecology, Kimberly Popendorf, assistant professor of ocean sciences, and Brain Haus, professor of ocean sciences;and Helena Solo-Gabriele, professor of civil, architectural and environmental engineering in the College of Engineering; and James Klaus, associate professor of marine geosciences in the College of Arts and Sciences.

HURAKAN: Improving Hurricane Risk Communication for Vulnerable Populations

Members of this team plan to develop new forecast products to communicate the risks and potential threats of approaching tropical storms and hurricanes, especially to underserved populations who, because of limited resources for adequate preparation and recovery, often bear a disproportionate burden of these natural disasters.

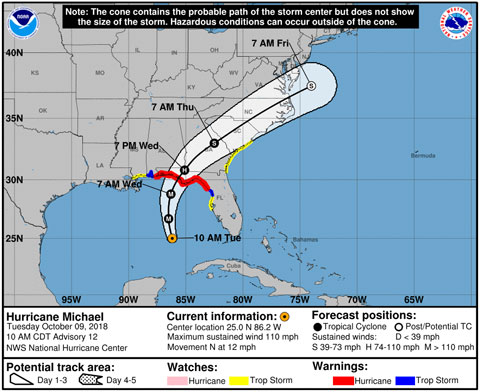

During the first phase of their project, researchers on team HURAKAN, named for the Mayan and Taino god for hurricanes, studied relevant literature and held focus-group sessions on the National Hurricane Center’s most-viewed and requested forecast products—particularly the cone of uncertainty. Reflecting the uncertainty in the probable track of the center of a tropical cyclone, the cone, researchers noted, “is easily misinterpreted and provides limited information about multiple hazards.”

“Some of the confusion is due to the probabilistic concepts presented in the forecast, the vast amount of information to process, and specific graphic elements that violate design guidelines,” the team led by Barbara Millet, research assistant professor in the School of Communication, wrote about the cone. “Participants were specifically interested in receiving clear information that would help them make informed decisions about what to do and when.”

To that end, the team plans to collaborate with the hurricane center on designing new forecast products that communicate “the minimal critical pieces of information to the maximum number of people from diverse backgrounds.” They also plan to develop a “best practices” guide that will be applicable to a range of natural and technological hazards.

In addition to Millet, other team PIs include: Alberto Cairo, associate professor in the School of Communication, Kenny Broad,professor at the Rosenstiel School and director of theAbess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy; Scotney Evans, associate professor in the School of Education and Human Development; and Sharanya Majumdar, professor andassociatedean of graduate studies at the Rosenstiel School.

Identifying, prioritizing, and validating green infrastructure approaches to enhance coastal resilience – Implementation of a data-driven test case in Miami Beach

For this project, UM experts who are exploring ways to restore living shorelines to protect coastal communities from waves and storm surge, plan to design and test the feasibility of installing a hybrid “green/grey” defense system—one that employs both natural and cement-based elements—off the coast of Miami Beach.

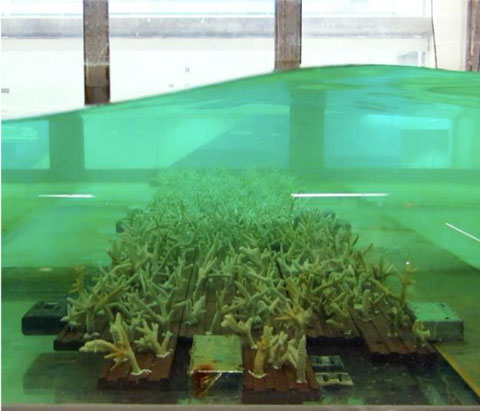

They will begin by identifying the risks on the most vulnerable shoreline sections of the City of Miami Beach—which already has spent millions raising streets and installing water pumps—and developing and testing the suitability of hybrid grey/green infrastructure options, particularly artificial reefs. Like the team studying toxic aerosols, this team is also using the Rosenstiel School’s SUSTAIN facility to conduct experiments.

Often made from sunken ships or cement modules, artificial reefs usually are deployed in deep water to create fish habitats and diving activities. But based on their collaborations with The Nature Conservancy and resilience experts from the City of Miami Beach, the team is considering artificial reef options that, using both natural corals and cement elements, could enhance both marine life and protect the coast. They’re also planning an outreach strategy to enhance participation in the project by stakeholders, politicians, and the public.

In their proposal, team members led by coordinating PI Diego Lirman, associate professor of marine biology and ecology at the Rosenstiel School, acknowledge that actually deploying an artificial reef off the coast of Miami Beach will be beyond their means, programmatically and financially. But the goal of the team is to “get to the point where we can use our general knowledge, partnerships, and products to pursue such additional funding from local and federal sources”—which, along with building cohesive interdisciplinary teams, is the goal of U-LINK funding.

Other team PIs include Andrew Baker, associate professor of marine biology and ecology, Brian Haus, professor of ocean sciences, and David Letson, professor of marine ecosystems and society, all at the Rosentiel School; Landolf Rhode-Barbarigos, assistant professor ofcivil, architectural, and environmental engineering at the College of Engineering; Sonia Chao, research associate professor at the School of Architecture; and Jyotika Ramaprasad, professor in the School of Communication. Jane V. Carrick, research associate in the Lirman Benthic Ecology Laboratory at the Rosenstiel School, is the project staff member.

With the Sunshine State so vulnerable to climate-induced changes, Bixby and Morgan said they’re not surprised that all three teams awarded Phase II funding are exploring solutions to problems directly or indirectly related to the changing climate. But they are pleased that the teams that applied for U-LINK’s second round of Phase I development grants have proposed a range of projects dealing with a number of other issues. They include projects that would enhance the health and well-being of vulnerable children; advance low-cost, collaborative space exploration; create structures that enhance the success of women in STEM fields; identify factors that lead to virality in social media; and provide low-cost palliative care to individuals in low-resource settings.

“When U-LINK was first conceptualized, we explicitly decided not to specify the ‘big problems’ that we’d like teams to address,” Bixby said. “The types of programs that our Phase II awardees and our Phase I applicants are building make it clear that we made the right decision.”

An essential component of the University’s strategic plan, U-LINK was established to encourage the development of multidisciplinary research projects that have the potential to address critical and complex societal problems—as well as the ability to attract the external funding needed to advance their proposals to viable solutions. But essential to both goals is nurturing a culture of collaboration at the U by developing a cadre of team scientists who can share best practices for working across disciplines to tackle multifaceted problems.

For this reason, all future and current U-LINK grant recipients will attend a daylong Team Science Workshop, where they’ll learn more about the art and language of interdisciplinary collaboration, and have access to the U-LINK collaboration space at Richter Library, a UM librarian, and research consulting services.