Written by: CARLOS HARRISON

First Star Academy

The room is filled with possibility, and promise. Ten soon-to-be ninth-graders, members of the University of Miami’s inaugural First Star Academy, are being taught to envision a future most of them would never have thought possible, and to seize their own potential to make it happen.

The instructor has scrawled a message on the white board at the front of the room. “If you chase two rabbits,” it reads, “you won’t catch either.”

Ramis Emmanuel Mercado, a “Teaching Artist” with the community group Motivational Edge, moves animatedly before the group, strutting and waving his hands for emphasis—like a hip hop artist performing for a rapt audience.

“How does that apply to life? You’ve got to be focused,” he says. “You’ve got to pick a direction and you’ve got to go for it…You’ve got to have decisiveness. You’ve got to choose. You got to say, ’This is what I want for my life. So anything that doesn’t align with that I’m not going to do.’”

The academy is an interdisciplinary collaboration between Miami Law and the School of Education and Human Development aimed at helping children in Florida’s child welfare system to overcome the obstacles created by their circumstances, and to shape better tomorrows despite their turbulent pasts.

It is just one of the many ways Miami Law faculty, students, and alumni are transforming communities, lives, and careers.

Some, such as 2017 Miami Law graduate Sawyeh Esmaili, have found a calling in tackling reproductive rights issues on a national and international level. Others, such as Miami Law alumnus David Humphreys, are stepping up to rebuild communities devastated by natural disasters, and investing in educational opportunity in his local community. Others, such as Professor and Associate Dean for Experiential Learning Kele Stewart and others involved with the First Star Academy, are working directly with the most vulnerable and disadvantaged in our society, and helping them build ladders to success.

Statistically, once kids like those in the Motivational Edge session get caught up in the foster care system, they face daunting odds. Nearly a fourth of the ones who “age out” of foster care at 18 and are sent out in the world end up homeless. Almost two-thirds of the males and a third of females get incarcerated. Barely 3 percent will earn bachelor’s degrees.

The First Star Academy aims to change that.

It is, fundamentally, a college prep program built, says Stewart, on three pillars: academics, life skills, and caregiver engagement.

“The philosophy behind First Star has two simple foundational principles,” she explains. “One is bring kids to a college environment so that they can start seeing and believing and dreaming about being on a college campus and see themselves here.

“The second one is build a support network around kids that stays with them and provides some level of consistency, as well as all the technical stuff—the academics, the tools to help with the college applications. But the more important thing is a support system that’s going to actually be there that’s focused on helping them get to high school graduation and then to college.”

Stewart is no stranger to making a difference. She also is co-director of the Children & Youth Law Clinic, which serves as both a practical training ground for Miami Law students and a real-life law firm representing foster care children in a variety of civil legal matters including dependency, health care, mental health, disability, independent living, education, and immigration issues.

“I like to say we amplify their voices,” Stewart says.

It’s a “holistic model,” she says, with an impact “that you can’t really capture by listing a bunch of cases. It allows us to really develop strong relationships with our clients, to problem solve for our clients, and to help our clients to feel as though there’s somebody rooting for them, fighting for them, and sharing their perspective in the child welfare proceeding.”

The mission of the First Star Academy seemed like a natural match. Founded by Hollywood film producer Peter Samuelson, the on-campus academy model rolled out initially at seven colleges including UCLA in 2011. Samuelson doesn’t take credit for the inspiration for First Star, but the self-made, British-born serial philanthropist says the founding principle matched the vision that drew him to the United States in the first place.

“I came to America because I felt that the American Dream was the most wonderful thing. There’s no German Dream or British Dream or Spanish Dream. But there is an American one. And it says we don’t care about your parents. We don’t care even if you’ve got parents. We care whether you will work hard. Because if you will, we’ll get you educated. You will have a worthwhile job…You too, can be happy.”

And foster kids, he felt, deserved that chance, too.

So does the University of Miami.

Beginning this past summer, the first contingent of 21 kids on their way to ninth grade spent a month living in a UM dorm. They studied language arts, math, and science, along with instruction such as the Motivational Edge coaching designed to make them better equipped to handle life on their own. They also got to participate in on- and off-campus activities such as a field day on the Edward T. Foote II University Greens, a visit to the Frost Science Museum, a service project at Historic Virginia Key Beach Park, a dance performance at South Dade Cultural Arts Center, a tour of Wynwood murals, and bowling at Splitsville.

The hope is that they’ll return every summer until they graduate high school and that the skills they acquire will lead them on to successful college careers.

“It’s going to impact far fewer kids than, sadly, are in the system, but it was my way of trying to create change in a way that felt like I had more control over at least the inputs,” says Stewart. “And, hopefully, we’ll get the outputs that other places that have done First Star Academies have seen.”

David Humphreys, J.D. ’83

Miami Law alumnus David Humphreys, J.D. ’83, had been making a difference in his hometown of Joplin, Missouri, long before an EF-5 tornado cleaved a mile-wide path of destruction through more than 22 miles of the city on May 22, 2011. It was, according to the federal government, “the deadliest single tornado on record in the U.S. since official records were begun in 1950.” It was also the costliest.

Miami Law alumnus David Humphreys, J.D. ’83, had been making a difference in his hometown of Joplin, Missouri, long before an EF-5 tornado cleaved a mile-wide path of destruction through more than 22 miles of the city on May 22, 2011. It was, according to the federal government, “the deadliest single tornado on record in the U.S. since official records were begun in 1950.” It was also the costliest.

It killed 161 people, left another 1,000 injured. It damaged 553 business structures, half of the district’s school buildings, the St. John’s Regional Medical Center, and nearly 7,500 homes—more than 3,000 of them severely or completely destroyed.

Total losses approached $3 billion.

For hours after the storm, Humphreys pulled people from the debris of their wrecked homes. He got home with a nail in his foot and shoeless because he gave his to a man who didn’t have any.

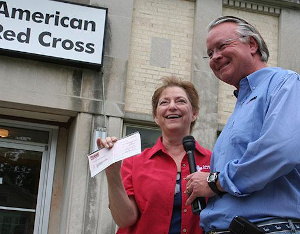

Then he gave $1 million to the local Red Cross through his company. “We don’t normally do that sort of thing publicly,” he says, “but we did it very publicly to try to encourage other businesses in the area to maximize what they would give also to the recovery effort.”

In addition he, with his wife, gave another $500,000 to the Salvation Army. On top of that, he says, he gave about $1 million to help his company’s employees get back on their feet. He didn’t stop there. He and his family took in three victims to live with them and offered a house he owned for another family to live in.

“At the end of the day I think we should feel some sense of duty to help out other people, however you accomplish that,” he says, “and to help other people out with our own resources and time and money and whatever else, as opposed to helping other people out with other people’s money and time and resources.”

Humphreys grew up in Joplin. His grandfather founded TAMKO in 1944, a roofing company that took its name from the first initials of the five states it expected to comprise its sales territory. Humphreys’ father took the reins in 1960 and guided the company as it expanded, adding manufacturing plants in five states—as far away as Texas and Maryland. It may have seemed like destiny, but Humphreys insists that taking over the family business was “the furthest thing from my mind. My father always said, ’Go find a job.’”

First, though, Humphreys got a degree. At Miami Law. He chose it, he says, because it offered him a chance to get an education that extended outside of the classroom.

“Miami was a very different place,” he says, “culturally, ethnically, and I think was a very important place for me, frankly, in terms of just growth generally by being in such a different environment.”

After graduation, he took a job with the largest firm in Joplin, doing medical malpractice defense work. A couple of years later he “decided at the end of it that I just didn’t like trials.”

He moved to New York to pursue a graduate degree in tax law. He wound up staying in New York after he finished, joining the Wall Street firm of Davis Polk & Wardwell as a corporate tax attorney. A year later, the firm sent him to France. “The only French I knew I learned in Berlitz in six weeks,” he says. "It was a grand adventure.”

When he got back from France, he says, “My father came through town and asked me if I’d ever thought about coming home.”

That was in 1989.

Humphreys worked as TAMKO’s general counsel for a couple of years, then in various operations and finance roles for a few more. In 1994, after his father died, Humphreys stepped in to run the company and continue its expansion into additional products.

He also became increasingly involved in philanthropic causes.

“It evolved over time,” he says. “Not in the sense of giving back because I always say that I didn’t take anything. But in terms of a sense of duty by being blessed with certain wealth and skills that I want to try to make the world a better place. At least to make my own community or where I’ve been a better place.”

He is a major donor to Miami Law and donated $1 million to establish scholarships at Missouri Southern State University. But the project he says he’s the proudest of is also one of the oldest of his endeavors—the private school he started with his wife 25 years ago, the Thomas Jefferson Independent Day School.

“There was no private, independent non-sectarian school, which was important to us,” Humphreys says. “To me, in terms of the impact that we’ve had, in any case, is providing that kind of resource for kids with talent to do exceptionally well and go on to really great things —from our community—that otherwise would not have had that sort of launching pad that you would find in a bigger city."

Sawyeh Esmaili, J.D. ’17

Sawyeh Esmaili, J.D. ’17, started having an impact while she was still at Miami Law. A Miami Scholar and Public Interest Leadership Board chair, she interned with Planned Parenthood Global’s Latin America Regional Office during her 1L summer.

Sawyeh Esmaili, J.D. ’17, started having an impact while she was still at Miami Law. A Miami Scholar and Public Interest Leadership Board chair, she interned with Planned Parenthood Global’s Latin America Regional Office during her 1L summer.

“I’ve always been interested in pursuing a career that would serve systematically silenced populations,” she says. “My experience with Planned Parenthood Global exposed me to the reproductive justice movement in Latin America, which feels much more grassroots than the movement in the United States. The human rights framework that it operates under permits more flexibility and, arguably, creativity when compared to the way reproductive rights are legally treated in the U.S. That framework serves as a useful guide in channeling the same creativity in other aspects of U.S. law.”

Born in California to an Iranian father and Colombian mother, Esmaili moved to South Florida after her parents separated. Her background shaped her and, in many ways, informs her areas of concentration.

“I’m interested in areas where the law intersects with identity. For example, in issues regarding the criminal justice system, reproductive rights, or immigration, the law chooses over whom it exerts control. The extent of this control is based on various factors, including but not limited to, race, class, gender, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

As a 2L, she interned with the Florida Justice Institute and participated in the Immigration Clinic. During her 2L summer, she interned at the Miami-Dade Public Defender’s Office, working on policy and direct service matters.

As a 3L, she helped in drafting an amicus brief in the Florida Supreme Court in the case of Gainesville Woman Care, LLC, et al. v. State of Florida, et al.

The amicus, filed in support of the ACLU/Center for Reproductive Rights’ lawsuit challenging the state’s mandatory 24-hour delay for abortions, focused specifically on exemptions for victims of human trafficking and domestic violence. It also noted the difficulties the act imposed for poor and immigrant women by requiring them to make two appointments with an abortion provider.

That same year, Esmaili was selected to present her paper, “An Incarcerated Woman’s Right to a Nontherapeutic Abortion: A Human Rights Framework,” at the LatCrit South-North Exchange conference in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The paper argues that denying an abortion to an incarcerated woman constitutes torture and a violation of the Eighth Amendment.

"Depriving a woman of an abortion as a result of her incarceration links the denial of legally available healthcare to her punishment,” she wrote. “A woman is, therefore, forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy as a part of her sentence.”

Now, she’s beginning a year-long policy-focused program as a Reproductive Justice Federal Fellow at the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health in Washington, D.C. The program, by its own description, gives fellows “hands-on policy advocacy experience and work on cutting edge reproductive health, rights, justice issues, particularly as they affect people of color and other marginalized communities.”

And, that, fits perfectly with what Esmaili sees as the “most important lesson I learned in law school.

“I learned a lot about how the law is created and developed, but more importantly I learned about the ways in which the law fails us,” she says. “A law degree is an incredible privilege, but I also view it as a way of trying to help voices that are being silenced. There’s so much that you can do with a law degree. You don’t have to be in a courtroom every day. You can engage in policy reform. There are so many other things. It doesn’t just have to be direct service. I think that’s kind of the cool thing about a law degree. It allows you a lot of flexibility to do whatever work you’re passionate about or interested in.

“It’s hard to say what direction my legal career will take because there is a lot of work to be done.”