MADRID - With the world already 1.1 degrees Celsius warmer than it was in preindustrial times, the United Nations COP25 climate change conference, which got underway on Monday in Madrid, couldn’t have been held at a more critical time.

Three students from University of Miami School of Law professor Jessica Owley’s UN negotiations class are in Madrid for the first week of the summit, where “they will have the unique opportunity to see how an international treaty is negotiated and to engage in problem-solving for the greatest problem of our era: climate change,” said Owley, who is accompanying the students on the trip.

A second group of three students will join the law professor for the second week of the summit, which ends on December 13 and is officially known as the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

This marks the fifth time that Owley, who specializes in environmental law with a focus on climate change law and policy, has attended the summit.

So far, a total of 24 COPs have been held, with the most notable being COP21 in 2015, at which the historic Paris Agreement was reached. As part of that accord, nearly every country in the world set goals to curb carbon emissions in an effort to stave off the most damaging effects of climate change.

At COP25, delegates from nearly 200 countries will nail down details left open by the Paris Agreement.

Dispatch 18

Dec. 10, 2019

A side event on national adaptation plans

By Massiel Gomez Fernandez

The side event “Financing NAP Processes: Strategies and Case Studies for Engaging the Private Sector,” was hosted by Winrock International and the Government of Vietnam. They shared their experience on how governments and partners have engaged the private sector to support the development, financing, and implementation of National Adaptation Plans (NAPs).

In addition, they shared their thoughts on how private sector entities can be engaged to understand opportunities of climate risk management, capture positive returns on investments, and identify and track the benefits to their respective organizations.

The speaker from Winrock International began his presentation by explaining the NAP process, defining it as “the process that enables countries to identify and address their medium- and long-term priorities for adapting to climate change.” He stated that the NAP process puts in place the systems and capacities needed to make adaptation an integral part of a country’s development planning, decision-making, and budgeting.

The speaker from Ghana addressed finance, saying that it is a key aspect in the long-term. However, finance is not the most important aspect; the power of people to understand what it means and the possibilities for them to make changes are the most important parts of the process right now, the speaker said.

The Vietnam delegation talked about its government’s action to engage PS in adaptation, stating that the government is committed to creating legal basis, applying the economic and market tools to ensure the effective implementation of policies and laws on climate change adaptation, and encouraging and creating favorable conditions for organizations (domestic and foreign enterprises) to invest and support the implementation of the NAP.

Dispatch 17

Dec. 9, 2019

Shoulder to shoulder

By Bethany Blakeman

I could feel the energy shift as I walked onto the metro car at Nuevos Ministerios, the transfer point to get to IFEMA, which is the convention center where COP25 is taking place. As we transferred from the Circular to the train headed towards the conference, the subway car was filled with colorful wardrobes and the song of different languages filled the air.

As we exited the metro and approached the conference hall, the low hum of the commuter chatter gave way to the insistent chants of “There is no planet B!” by young protesters lining the sidewalk in between the metro exit and the entrance to COP25. The energy in the air intensified, and I felt a rush as we continued walking toward the entrance.

As I enter Week 2 of the negotiations, I feel that there is a gap between the work being done through careful diplomacy and the demands for more immediate action by the citizens who will bear the consequences—the youth of the world. As I participate as an observer this week, I hope to see some sort of gap-bridging in this regard. Do the teens protesting not fully understand the nuances of international diplomacy and the challenges of governance, or are they right in demanding more? Is enough truly being done?

At our morning briefing, we got a quick low-down of where we would be picking up where Week 1 left off, and Article 6 is still the big-ticket item of the official negotiations. In addition to these official negotiations, I will be focusing on issues related to the oceans. Last week, the government of Chile announced that this year’s COP is the “Oceans” COP. I am looking forward to finding out what exactly that means as I navigate the negotiations and side events throughout the week.

Today I attended a handful of side events. What impresses me the most about the side events is the level of engagement by stakeholders. During the Q&A session at one of these events, the first question came from a woman who is a member of Parliament in Uganda, followed by a question from a member of Parliament from South Africa. After a few questions were posed to the panel, one of the panelists started by asking how many people in the room were government representatives or elected officials. About 25 percent of the room raised their hands. I was struck by the willingness and eagerness of these representatives to learn from each other. A common theme in the conversations I observed today is that the implementation of these negotiations happens at the subnational level, which is why the participation of these regional officials is so important. These side events and the conversations that they spark seem to be where much of the momentum lies. I am looking forward to the rest of the week and observing the official negotiations.

Dispatch 16

Dec. 9, 2019

Negotiations and the power of pavilions

By Maria Ramirez

During our first day at the negotiations, we had the opportunity to attend the Body for Implementation (SBI51) and the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA51). These negotiations relate to the impact of the implementation of response measures serving the Convention, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement. During negotiations, we observed that even though the co-chairs of the secretariat proposed draft occlusions, the majority of representatives accepted them; however, other representatives such as a Saudi Arabia and Ghana wanted to continue the discussion of the articles before reaching an official conclusion.

Next in the afternoon, we attended “Zero Hours: Citizen Mobilization for Climate Actions.” During this presentation, the keynote speaker explained how people and companies are related to climate change actions, saying “citizens’ role in climate mitigation is significant” and “companies and citizens can really change the world like Tesla auto cars.” During this presentation, other speakers presented products that we can use as a way to take action against climate change.

We also visited the pavilions that represent each country that is in attendance at COP25. The pavilions have presentations during the day that explain issues and actions that we can take to address climate change.

I believe that during this week, we can learn aspects of environmental law and international law that will help us develop our final project, which consists of writing a policy brief.

Dispatch 15

Dec. 9, 2019

Miami’s new delegation arrives

By Jessica Owley

As the second week of COP25 begins, UM has a fresh new delegation arriving. The second week of the COP has a different flavor than the first week. More people attend the second week. There are more high-profile players (think Greta Thunberg and Alejandro Sanz). There is more pressure to try to make progress this week. Like students writing a paper, sometimes negotiators need the pressure of an approaching deadline to get down to business.

While exciting, week two can be challenging for a new delegation. I am joined this week by UM law students Bethany Blakeman, Maria Ramirez and Massiel Gomez Fernandez. They are plunged into an event in progress that is flowing with acronyms and shorthand that can be hard to grasp. Our week one delegation has helped the transition with their posts and notes.

The key issues this week are going to be climate finance (how do we pay for all of this), NDCs (including complicated discussions of carbon markets), ambition (can we get countries to increase their commitments?), oceans and adaptation (including loss and damage). Launching into week two with lots of exciting topics still before us.

Owley and students Natalie Cavellier, Gabriela Falla and Romney Manassa filed dispatches from Madrid for the first week of the conference.

Dispatch 14

Dec. 7, 2019

Epilogue

By Romney Manassa

As I write this, I am on a flight from Madrid to Miami, joined by my two colleagues turned close friends. It is hard to believe that that our time at COP25 is over. We had already gotten used to waking up before the crack of dawn everyday to attend our 9 a.m. debriefs, led by our veteran NGO contact, where we learned all the complexities, challenges and tribulations of these negotiations.

While I wish I could attend the second and final week of the conference—obviously, I have finals to get around to—I am incredibly grateful to have had the opportunity to see firsthand the sorts of things I had only ever read about. It is an immense honor to have been selected for this unique experience, to join two amazing peers and our visionary professor in representing the University of Miami School of Law in the biggest annual climate change conference. Only a sliver of humanity is privileged enough to access a secondary education, let alone be able to participate in programs that immerse them in a world far removed from the average person, yet of great consequence to all of humanity.

Needless to say, my gratitude is boundless, and I leave COP25 inspired and invigorated by all that I have seen and learned, not only about climate change, but about international law, diplomacy, geopolitics, grassroots activism, the art of negotiations and so much more.

An issue as complex and challenging as climate change touches on a myriad of disciplines and subject matters, from the psychology and game theory governing these discussions, to the economic, social, political, and even philosophical implications of both its impact and its proposed solutions. I never imagined I would glean so much in just one week.

I won’t belabor the heartfelt and mutually shared sentiments expressed in Natalie’s beautiful dispatch, but it should go without saying that I echo all of it: This was a demanding and often grueling experience, but it was worth every second, from dawn to well past dusk. I believe an experience is only as good as those you share it with, and having folks as hardworking, compassionate, earnest, and fun as Natalie and Gabriella made all the difference. Their quality as both dependable colleagues and exemplary human beings is a testament to Miami Law and a boon to the legal community.

I also wish to thank Professor Owley for spearheading this amazing initiative, which marks the first time that Miami Law has taken part in this conference. Only a handful of U.S. schools were present, and it left me even prouder to be a ’Cane. I am excited for the rest of the team that will be taking the baton as the COP draws to a hotly anticipated and consequential close, and I am hopeful that future students will enjoy this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Finally, I wish to thank all my loved ones—my spouse, friends, family and fellow students—for supporting and encouraging me through this journey. That includes you, dear reader, for taking the time to follow along and learn more about COP25! It’s been one heck of a ride, and it was a pleasure sharing it with you.

Dispatch 13

Dec. 6, 2019

How the sausage is made

By Romney Manassa

I enter our last day at COP25—and the halfway point of the two-week negotiations—with equal parts excitement, trepidation, disbelief.

Excitement at the opportunity to see how the latest installment of these often-dramatic negotiations will go and what amazing side events, exhibits and panels await; trepidation at the very real possibility that delegates may remain stubborn, uncooperative and sclerotic about making some of the most important decisions in the 21st century; and disbelief that I could be so lucky to have the pleasure and privilege of seeing all this play out firsthand, alongside some of the finest peers and colleagues I could now call friends.

As frustrating and ineffectual as all this can seem, we take for granted how much progress has been made because of international discussions like this. For all the global efforts that drag on, fall short of their promises, or never materialize, there are many more that succeed, to the point that we hardly notice or think twice about their fruits.

The fact that we can cheaply send and order mail or packages virtually anywhere in the world comes from the Universal Postal Union, a UN agency originally established by a 19th century treaty signed in Switzerland—hardly a household name.

Virtually all the goods and services we enjoy have some foreign component, thanks to a complex web of treaties, agreements, and model laws that lubricate international trade through uniform standards for classification, safety, shipping, customs and so on.

Our ability to travel anywhere in the world at a moment’s notice—in one of over 34 million international flights annually—is courtesy of several global institutions and agreements that allow airlines, aviation regulators and air traffic controllers to speak the same language and operate along the same standards.

The eradication of smallpox—an historic scourge of humanity that we are fortunate not to have to think twice about—was accomplished under the auspices of the World Health Organization, which also helped develop a vaccine for Ebola.

These achievements and more are the fruits of numerous unseen diplomatic talks and meetings that spanned years and even decades. Most of them would have been unthinkable in the lifetimes of our parents or grandparents; who could believe that the world would come together to vanquish diseases, solidify economic ties, and make traveling halfway across the globe as cheap and easy as traveling in your own country? Who could believe that the slow, messy, and frustrating circuit of summits and agreements and pledges could actually pan out to something tangible and beneficial?

I can only hope that someday we’ll be saying the same about climate change, following a concerted global effort to address this existential threat. It may be a tall order given the state of these talks currently, and the seemingly insurmountable challenge before us.

But the same was said about a lot of other global achievements we now have the luxury of taking for granted. Let’s hope that precedent pans out, for all our sakes.

Dispatch 12

Dec. 7, 2019

Talk shop

By Romney Manassa

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower once said that United Nations “represents man’s best organized hope to substitute the conference table for the battlefield,” and that only through its “truly democratic processes can humanity make real and universal progress toward the goal of peace with justice.”

As Supreme Allied Commander of the Second World War, Eisenhower saw firsthand the carnage that results from the absence of a global moral framework, predicated on obligations towards one another as fellow humans, regardless of where we happen to be born. It was the weakness and gradual erosion of the UN’s predecessor, the League of Nations, that both precipitated and signaled the descent into war.

Not unlike the Second World War, which ultimately catalyzed the current international legal order and the UN as its guarantor, climate change presents an existential crisis of our making—one that should bring us to the conference table to reflect, cooperate and take collective action.

But as I embark on my fourth day of COP25, I am wavering in my own optimism and idealism about this framework. With now dozens of meetings and sessions between us, we are noticing the same patterns: stubbornness, stodginess and stonewalling.

Instead, we’ve each seen progress stalled and negotiations detailed by geopolitics, self-interest, and even pedantry. Delegates cannot agree on the fundamental starting point of their talks, or on a common understanding of the proposed terms and definitions; in some cases, they even disagree about the scope or purpose of their role here. I learned this morning that some of these intractable debates and disputes have persisted for years, with apparently little to show for it. Some delegates and meeting facilitators were keen to remind everyone of this fact, I think as much out of exasperation as to shame them into finally compromising.

I can honestly see why so many are cynical about this process, if not the whole framework of diplomacy, summits, conferences and the like—all talk, little action. One needn’t attend these events to feel this way of course. Many people have long lost hope in the notions of multilateralism and international comity.

How many conflicts, genocides, and human rights abuses have come and gone without action by either the UN or the international community? How many autocrats and war criminals have gotten with these heinous acts, shielded in large part by the same sovereign prerogative that deadlocks these meetings? And how much damage has already been wrought on our global environmental and climate systems by years of endless assemblies, nonbinding agreements, and fulfilled pledges—i.e., lots of talk?

But it’s worth asking the corresponding question: How many horrible things haven’t happened because of this flawed, often ineffectual system of ours? What about the wars that never started, the nuclear missiles that were never launched, the people that were never exterminated? For obvious reasons, it is easier to know and dwell on the awful things that occurred than the awful things that didn’t.

Though it’s certainly debatable, I think that to some extent, we’ve managed to head off a lot of crises and conflicts because we’ve given the world a shared platform and process through which they can air out their grievances, stake out their positions, and jostle for international support—just as they’re doing at COP25—rather than unpredictably taking matters into their own hands, as was historically the case.

Indeed, is there any other way a global response to climate change could be carried out? It’s all or nothing: Either most of the world commits to reducing emissions and mitigating climate change, or the problem gets worse—for everyone. If, as in the pre-WWII system, it’s every nation for itself—without coordination, transparency, and, yes, talking—then not enough can be done to tackle the problem across the board.

Barring some sort of fanciful global dictatorship—with all its infeasibility and immorality—there is simply no other conceivable way climate change (among other global problems) could be resolved. The seemingly endless talking and bickering might be disappointing, frustrating, and despairing, but it’s all we got. Better that the whole world is at least speaking the same language, at the same table (so to speak)

To paraphrase a quote often attributed to one of Eisenhower’s contemporaries: “The United Nations is the form of international order, except all the others.” I’ll try to keep this in mind as I find myself despairing at the state of this climate conference table.

Dispatch 11

Dec. 6, 2019

When worlds collide

By Gabriela Falla

Greta Thunberg has finally arrived in Madrid after her long transatlantic sail and is scheduled to take part in a climate march on Friday evening. Greta arrived just a day after the Young and Future Generations Day (YFGD) at the COP, which showcased and celebrated youth climate action.

The opening ceremony of YFGD kicked off the day, and young leaders from around the world shared inspiring climate action stories. Later in the afternoon an intergenerational inquiry event was held where decision-makers and youth leaders came together and discussed how young people can become involved in further implementing the Paris Agreement.

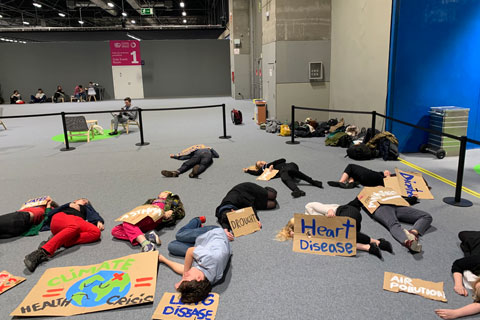

Young people across the globe are calling for immediate action on climate and are pouring into the streets to let their frustrations be heard. Here at COP, youth leaders staged a die-in demonstration at the entrance of the conference hall and held handwritten placards to emphasize the effect of climate change on the global health crisis. As parties and observers shuffled into IFEMA to attend events and meetings all day, they were forced to reckon with the protesters and their message: “se os han acabado las excusas, y a nosotras el tiempo” (your excuses are over, and so is our time). In order to achieve the goals that were set out in Paris, strong political will by the parties is necessary.

Young people across the globe are calling for immediate action on climate and are pouring into the streets to let their frustrations be heard. Here at COP, youth leaders staged a die-in demonstration at the entrance of the conference hall and held handwritten placards to emphasize the effect of climate change on the global health crisis. As parties and observers shuffled into IFEMA to attend events and meetings all day, they were forced to reckon with the protesters and their message: “se os han acabado las excusas, y a nosotras el tiempo” (your excuses are over, and so is our time). In order to achieve the goals that were set out in Paris, strong political will by the parties is necessary.

It has been interesting to see the two worlds collide at COP25 and in Madrid. On one hand we see fiery young leaders demanding climate action now, while at the same time we see party delegates slow to act regarding major decisions. As the youth quickly mobilize in Madrid and around the world, it begs the question: Will real progress be made in Madrid before the end of next week? Though talk of ambitious national commitments to climate have been discussed at this COP, achieving these goals will be a challenge considering the pace at which the negotiations are going.

Regardless of the outcome at COP25, I am thrilled I was able to watch youth leadership in action at COP and along the streets of Madrid. While I was writing this blog post at the United Nations pavilion, an interview was going on beside me with Penelope Lea, the second youngest UNICEF ambassador of all time. I learned that Penelope, while only 15 years old, is the first climate and environmental activist ever elected as a UNICEF ambassador. I sat beside her mother while Penelope was being interviewed, I could not help but feel hopeful. Penelope stated in an interview, “I believe that the climate crisis requires extraordinary collaboration and unity, extraordinary actions, and extraordinary love.” I could not agree more.

Dispatch 10

Dec. 6, 2019

Jet lag is real, but so are finals

By Natalie Cavellier

COP is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Unfortunately it also falls during finals. Instead of focusing on the technical aspects of the COP in this post, I want to focus on my fellow students who have accompanied me here, our experiences and their amazing work taking notes and supporting our partners while also attempting to maintain balance and study for finals.

Both Gabriela Falla and Romney Manassa are amazing individuals who have made this trip even more enriching. Their positive attitudes and dedication to getting the most out of the trip and COP despite being jet lagged, stressed and above all always hungry have made the event unforgettable.

COP is exhilarating and exhausting in a way that is difficult to describe. Having finals on the brain enhances that feeling of urgency. Days begin at 7:30 and often don’t truly end until two or three in the morning. I question how I’m still writing this blog post. I have to attribute some of it to the energy of the conference; the rest has to be the energy of my teammates, who keep going, keep discussing what they’ve seen, and keep debating the process of change. The fact that we are still having in-depth conversations about the political process, minutia of meetings, and side events, is astounding.

COP is exhilarating and exhausting in a way that is difficult to describe. Having finals on the brain enhances that feeling of urgency. Days begin at 7:30 and often don’t truly end until two or three in the morning. I question how I’m still writing this blog post. I have to attribute some of it to the energy of the conference; the rest has to be the energy of my teammates, who keep going, keep discussing what they’ve seen, and keep debating the process of change. The fact that we are still having in-depth conversations about the political process, minutia of meetings, and side events, is astounding.

We spend the days attending meetings, searching for coffee, and trying to squeeze in some time for outlining or study. While we aren’t required to attend meetings, following a topic means that attendance is important or even just of interest. The conversations in meeting rooms can be confusing, especially if you haven’t been closely following COP conferences from years past. Some of this process has involved in-depth investigation of the history of specific mandates. It seems like every time something is clarified, a meeting ends, or there’s a moment to rest, another question arises, or another event beckons. Indeed, COP keeps you engaged and on your toes at all times.

After we finish attending meetings or side events around 6 or later, we go on the hunt for food. The quest for good food has been more difficult than you would think given we are in a city well known for its gastronomy. Despite the difficulties, we have had some great meals. Eating Thai delivery in our hotel room, while researching different COP and UN documents and studying for finals has been one of my favorite memories of the conference. Between serious conversations about the meetings attended that day, writing these posts, and outlining, I’ve gotten to know my teammates well, laughing over melted ice cream, taking the metro in the wrong direction, and deliriously hunting for a restaurant after a long day.

I don’t want to gush, but I think it’s important to recognize the dedication these two have. During an exam period, they chose to travel abroad to attend a conference, assist and provide notes and information to a partner organization, and have pushed me throughout the week to make the most of this experience. Sharing this with people who are passionate and dedicated is more than I could have asked. I really want to thank them and Professor Owley for not only the wonderful opportunity, but for the company. I know that even after I return to Miami and plunge into exams, when I reflect on this experience, I will be forever grateful for the late-night study sessions and the memories and knowledge gained.

Dispatch 9

Dec. 6, 2019

Backroom discussions

By Natalie Cavellier

Now that I’ve grown somewhat accustomed to the COP proceedings, I’ve begun to form some opinions on the event’s organization. First, I must say, for an event that was, up until a month ago slated to be held in Chile, the event is remarkably well put together. My opinions and some critiques are around the general organization of the event with separate side events happening concurrently with the negotiations.

The side events and pavilions are supposed to allow stakeholders and others to be involved in this somewhat nuanced process. However, instead of feeling like these events are going on in tandem with the negotiations, these events are separated, both by distance and type of participant. These are simply my observations, but this is how it has appeared in my short experience at the COP25.

Rooms where the negotiations are taking place are located on the far side of the conference venue. The area is filled with party negotiators, observers, and reporters. Party delegates sit in scheduled meetings and then are given “homework” for the next session. Outside these sessions, the party delegates meet with each other and attempt to come to a consensus. Sometimes the decisions may be on procedural topics, like what a meeting or document will be called—contention around terms can impede the progress of a talk completely. The sub-groups who meet to negotiate terms, timelines and other minutiae are tasked with advising the main bodies, the COP and CMA with advisory opinions, conclusions and decisions. However, all these discussions take place in the regimented and procedural backrooms of the conference. I don’t mean that these are so called “backroom” meetings, in the colloquial sense. Instead, these meetings are physically in the back rooms of the IFEMA conference center.

These formal meetings stand in direct opposition to the lively and colorful events taking place in front of the conference center. With their visuals, colorful decorations, and conference “swag,” the pavilions are easily accessed and host a variety of events with stakeholders, corporations and diplomats. The side rooms have additional events, some presentations boasting impressive visuals aids. In comparison with the negotiations, these events and exhibits are accessible. The speakers and panel events are comprised of diverse sets of experts. Despite the diversity of these speakers and attendees, the actual influence these events and speakers have on the negotiation process is unclear. The delegates and the parties they represent enter the process with a predetermined set of positions.

From my perspective, it doesn’t seem like the stakeholders are being given an opportunity to be involved in the COP itself. Instead it seems like the pavilions and side events are a distraction from the negotiations going on in the back of the conference center. Distraction may be a strong word, but as much as I myself have benefitted from the events and pavilions, the goal of the COP is for the parties to reassess and negotiate agreements under the UNFCCC. I find it hard to believe that the side events have a substantial impact on the proceedings of the negotiations during the conference.

While sitting in the South African pavilion enjoying my free coffee, courtesy of the German pavilion, I overheard an interesting conversation, which resulted in this post. A man one table over was saying that the side events are great because they bring together so many different stakeholders who are involved in work around climate change, and they foster partnerships. However, the events probably don’t make a difference in how the negotiations proceed. His suggestion was that the events should take place a week before the negotiations, so that the delegates have a chance to attend these events, absorb some of the knowledge, and connect with the different stakeholders. This comment made me think about the entire nature of the conference, who it benefits, who has access, how negotiations happen, what the benefits of the side events and pavilions have, and various other larger thoughts, to be saved for a different time.

I don’t want to sound like a cynic, but it’s hard to remain positive when meetings of the sub-groups devolve into discussions of the small details of a phrase and block the passage of important guidelines, decisions, recommendations, and draft texts that could make a real difference in combating climate change. While the pavilion and side events are informative and showcase some of the most innovative solutions to climate change, the contrast between the two processes can be upsetting. One is hopeful and encourages action, while the other hinders those actions from being implemented due to politics or technical inflexibilities. I’d like to be positive and say that the partnerships and discussions happening in the front of the conference will lead to more productive talks in the future, even if they are not now.

Dispatch 8

Dec. 5, 2019

Theatrics and landing zones

By Gabriela Falla

Since arriving at COP25, I have been following Article 6 negotiations closely. Article 6 remains the last unresolved section of the Paris Agreement rulebook. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement sets out three mechanisms to raise climate ambition and promote sustainable development as well as environmental integrity through market and “non-market approaches.” Essentially, the goal of Article 6 is to allow parties to cooperate with one another in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) in efforts to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

The sections of Article 6 under review in the negotiations are sections 6.2, 6.4, and 6.8. Under Article 6, paragraph 2 (6.2), parties are requested to develop guidance for robust accounting to be applied when cooperative approaches are taken toward NDCs. Article 6, paragraph 4 (6.4) allows for international cooperation by setting up a new international carbon market as well as a governing body to supervise it. Lastly, Article 6, paragraph 8 (6.8) allows for the use of non-market based cooperation.

Whether or not the delegates will deliver real results on this large agenda item is still unclear. Though we are only in week one of the negotiations, at each meeting party delegates are pushed by their meeting co-facilitators to collaborate with one another in order to make progress on the task at hand. With only one informal meeting a day on the matter, delegates are constrained to about one or two hours to inform the co-facilitators and their colleagues of potential improvements for the next iteration of the Article 6 text that is to be drafted at the end of the week.

Tensions are high at the meetings, and the co-facilitators are in a position where they continue to urge party delegates to articulate their concerns and suggestions succinctly so that every party can be heard during the limited time they are all together in one room.

Though some party delegates provide constructive feedback to the co-facilitators regarding what changes they would like to see in the next iteration of the draft, other party delegates continue to stall the process. In one meeting I attended, the co-facilitators intended on using the two hours of allotted time to go over the drafted text of sections 6.8, 6.4, and 6.2. Forty-five minutes into the meeting, Article 6 had yet to be discussed.

Whether some party delegates are stalling in order to hinder progress, or whether they are concerned about real procedural issues, is up for debate. The co-facilitators, aware of such tactics and their limited time, have strongly urged party delegates to limit their input to comments regarding where they see potential “landing zones” in this negotiation, or the zones of possible agreement between the parties.

Unfortunately, some party delegates were unwilling to heed the advice of the co-facilitators and continued to use up their time to outline their positions on each section of Article 6. This has been particularly frustrating to watch, given that the body has been working on making progress on Article 6 for years. Though party delegates who intend to move forward with Article 6 make their frustrations known to their colleagues, it seems to have very little effect.

I found the theatrics of the negotiations particularly interesting, so I asked one of my contacts whether the same party delegates I identified stalling the Article 6 negotiations have a tendency to hinder progress in other meetings they attend. Interestingly enough, I learned that dynamics between the party delegates change from room to room depending on what issue is at stake. While a party delegate can angrily reprimand a counterpart for obstructing progress in one meeting, that very same delegate may use the very same tactics to hinder productivity in another meeting where its interests do not align. Ultimately, it seems, hypocrisy does not matter in the process.

Dispatch 7

Dec. 5, 2019

Strange bedfellows

By Romney Manassa

It’s not everyday that you see China, Iran, Palestine and the United States in the same room—and debating issues more or less amicably—aside from the occasional, if light and indirect, jabs.

Given what’s at stake, it’s not surprising to see countries that otherwise don’t get along—or that don’t even have formal diplomatic relations—having a seat at the same table to find common ground and hash out a solution. It speaks volumes that countries that are hostile to each other, or even to the idea of climate change altogether, nonetheless feel compelled to take part in this process. (I am sure some readers were also surprised to learn that the U.S. has sent a delegation to COP25.)

Global problems like climate change, by definition, don’t care about political squabbles, rivalries, or borders; they’ll keep getting worse and impacting us all no matter how we feel about each other. Contrary to popular belief nowadays, multilateralism and international cooperation are not fluffy idealism. They reflect the sober, pragmatic reality that, like it or not, we’re stuck on this fragile planet together and had better sort ourselves soon. That is why even mutually distrustful or cynical governments are, at the very least, making themselves present at this process.

Global problems like climate change, by definition, don’t care about political squabbles, rivalries, or borders; they’ll keep getting worse and impacting us all no matter how we feel about each other. Contrary to popular belief nowadays, multilateralism and international cooperation are not fluffy idealism. They reflect the sober, pragmatic reality that, like it or not, we’re stuck on this fragile planet together and had better sort ourselves soon. That is why even mutually distrustful or cynical governments are, at the very least, making themselves present at this process.

Of course, there are plenty of self-interested motives at work here, and some countries are participating—at least in part—to rein each other in or ensure their national interests are represented and not being infringed upon. Even the most good-natured and well-intentioned delegates have governments they must answer to and various other considerations and obligations to take into account (seen and unseen).

It’s a messy and complex process, and it can be frustrating to see one meeting after another go by with seemingly little progress or agreement. Yet when one considers how hard it is for just one country like the U.S. to overcome polarization, partisanship and political gridlock, one can better appreciate the monumental, unprecedented task of getting about 200 countries—each with their own complex political and socioeconomic dynamics, both internal and amongst themselves—to agree on a common vision and approach to addressing climate change.

Given humanity’s long history of constant warfare on a visceral and superficial level, it is fascinating to see even enemies maintaining some modicum of civility and cooperation as they deliberate on one of the biggest issues facing our planet.

Dispatch 6

Dec. 4, 2019

Punching above their weight

By Romney Manassa

What do Bhutan, Palestine, Malawi, and Grenada have in common? In most contexts, they are small and not particularly powerful; In fact, to many Americans, most of them are totally obscure.

But at COP25, they are diplomatic heavyweights.

One of the most fascinating characteristics of this conference—as well as international summits and negotiations generally—is the outsized role played by countries that rarely get the geopolitical spotlight.

In my estimation, the emblematic examples are small island nations—Nauru, Tuvalu, Tonga, and the Maldives, among others—which have an immense presence here. Their nationals seem to make up a disproportionate number of visitors and observers, and their delegates have been at virtually every conference and event I have observed. Their words carry a lot of weight, not only because their negotiators are adept, but because they are literally on the frontlines of the climate change fight.

Yet even nations not yet facing the more immediate and visible existential threat of climate change are surprisingly influential actors here.

Nestled between the Asian giants of China and India, the mountainous nation of Bhutan has fewer people than Miami-Dade County. Yet it one of the meetings I observed, it was formally representing a powerful coalition of countries across the world, which accorded its delegation tremendous weight and responsibility relative to its size.

Similarly, the Caribbean nation of Grenada, with a population smaller than the number of UM alumni, was selected to facilitate a meeting that included the likes of China, India, and the United States. The idea that such a tiny country would lead discussions among the world’s largest and most powerful states—including putting them in line if need be—would no doubt strike the casual observer is absurd.

The State of Palestine, which is almost exclusively known for its perennial conflict with Israel, would seem to be the furthest removed from the climate change issue. Yet its delegation has been among the most proactive and involved of any participant, sometimes speaking on behalf of the G77, an influential bloc of 135 developing nations—more than half of all UN member states—which it currently chairs.

Punching above one’s geopolitical weight is par for the course of every COP. As one of our NGO contacts had explained earlier today, many smaller and/or poorer countries are known for their deft and effective delegates, including Egypt, Brazil, Mexico and Singapore.

I’ve seen it for myself, too, from those nations and the likes of Antigua and Barbuda, Botswana, Costa Rica, Nepal, Colombia, Eswatini, and the Bahamas. Their comments and contributions are often highly technical, meticulous, and substantive, and seeing them go toe-to-toe with countries that have far more resources is something to behold.

Strange as it may seem, this leveling of the global playing field is the cornerstone of our international system, reflecting the principle of sovereign equality: that all countries—regardless of their size, wealth, and power—have the same legal rights and treatment under international law and diplomatic protocol.

This concept, enshrined in the UN Charter and post-World War II legal order, is largely why countries are no longer in the constant state of warfare that characterized international relations for millennia. (Which, of course, is not to ignore or minimize the very real and tragic violations that still occur.)

Sovereign equality is also what allows for countries to come together at summits like COP25 to hash out solutions to global problems. Both the causes and consequences of climate change don’t respect borders, which is why all nations need to work together to address it. Only by giving them a seat at the table—with the same voice and input as everyone else—is such multilateral coordination possible.

Given the amount of talent I’ve seen from every corner of the globe, it is clear to me that we need all the perspectives and ideas we can get, both in and beyond the COP process, to tackle an existential threat as complex and vast as climate change. In this era of nationalism, protectionism, and insularity, a multilateral approach among the community of nations is not soft or idealistic—it’s pragmatic and vital.

Dispatch 5

Dec. 4, 2019

Presenting at COP25

By Gabriela Falla

On our second day attending COP25, Professor Owley, Natalie Cavellier and I were given the opportunity to present on a Cornell University panel titled Global Engagement with Universities, Countries, and NGO Partners to Enhance Climate Ambition. Preparing for the presentation was exhilarating. Given that it is our first time attending a COP, assuming a role as a panelist was an incredible experience.

UM law students Gabriela Falla, right, and Natalie Cavellier present at a COP25 panel.

We presented on the role universities can play in advancing climate ambition. Climate ambition has become an important goal at this year’s COP, and as a result, delegates have insisted their colleagues aspire to ambitious climate goals during meetings and negotiations. As the global climate crisis intensifies, the push to deliver at COP25 reverberates. The pressure is definitely on.

Patricia Espinosa, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, set the tone when she said, “The world’s small window of opportunity to address climate change is closing rapidly. We must urgently deploy all the tools of multilateral cooperation to make COP25 the launchpad for more climate ambition to put the world on a transformational path towards low carbon and resilience.”

During our presentation, we spoke on our experiences as interns of the University of Miami’s Environmental Justice Clinic and our role in advancing environmental and climate justice in our local community. Because of Miami’s proximity to the coast and its issues with sea level rise and salt water intrusion as well as storm impacts, environmental justice is paramount in ensuring the right to a healthy environment, both natural and built, regardless of race, gender, income, or nationality.

At the clinic, we increasingly view our work through the lens of climate and aspire to engage with our community to increase resiliency and equity. Together, Natalie and I presented about the anti-displacement and policy projects our classmates and I have been working on throughout the semester.

To be able to present our work at the Environmental Justice Clinic and to be given the opportunity to represent the University of Miami School of Law at COP 25 was an honor and a privilege. On day three of the conference, we will continue to do so by wearing our University of Miami Environmental Justice shirts.

Dispatch 4

Dec. 4, 2019

The negotiations begin

By Natalie Cavellier

The excitement and novelty of the first day of the conference has given way to more serious conversations—and chocolate. On Tuesday, chocolate bars met us at the entrance to the COP. Change Chocolate, a bar that boasts having the “answer to the climate crisis written on trillions of leaves,” turned out to be delicious and a saving grace in my day, which was filled attending back-to-back meetings.

Where Monday was spent acclimating ourselves and attending side events and pavilion presentations, the second day of the conference was more about the actual negotiations. The day started with a discussion of the different meetings and negotiations that would take place. Along with students from Vermont Law School, we collectively decided on which meetings we would attend.

Being in the meeting rooms, where party representatives were speaking and trying to promote their countries’ interests, was a whole different experience. The meeting rooms are large square boxes that look like they’ve been plopped inside the conference center. Each box is topped with a lid to contain the noise within. Observers sit around the side of the room against the wall. The parties sit around a square and are supervised by a facilitator, whose job is to guide the committee to an agreement, or to create a draft decision or conclusion to present to the COP or CMA (Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement). Thus far, no decisions have been reached—nothing even close to a decision to make a decision.

Following back-to-back meetings, Gabriela Falla, a fellow Environmental Justice Clinic Member, and myself presented alongside Professor Owley at a side event coordinated by Cornell University. Gaby and I spoke about our work with the clinic and on the issue of environmental justice. The event was focused on how students and universities can get involved in combating climate change. Since we were the only law school represented, we spoke about the role of clinics and the role that the Environmental Justice Clinic has played in working on issues of climate disclosures, displacement, and municipal equity. While our work is on a smaller scale than the work of some of the other organizations represented, like the World Bank, local level change is just as important and impactful.

Dispatch 3

Dec. 3, 2019

The politics of pavilions

By Romney Manassa

Climate change is an inherently global problem that consequently requires a global response. Hence, every COP has sought to involve as many global stakeholders as possible, from NGOs and universities to governments and international organizations.

With so much of the world represented or watching closely, the COP has increasingly become an opportunity for countries to show their best face—not only as responsible actors in the fight against climate change, but as friendly, interesting, and even cool.

Indeed, one of the most immediately striking aspects of COP25 was its World’s Fair-like atmosphere. In addition to sending delegations and negotiators, many countries set up national pavilions, which vary in size, style, complexity and activities, but share in common the baseline desire to make the nation’s presence known, if not a little endearing.

Almost the moment we walked in, we were invited to enjoy free churros and hot chocolate—courtesy of the Government of Spain, we were told. Having rescued the COP from its abrupt cancellation just a month before it was to begin, Spain garnered considerable respect and influence. Its salvaging of the world’s most important climate conference was officially motivated by the belief that “multilateral climate action is a priority for both the UN and the EU, and one which demands the highest commitment from all of us.”

Whatever its motivations, Spain also seems to view the COP25 as an opportunity to showcase its progress and culture. Drinking fountains throughout the conference advertise Madrid’s clean natural water source, which we’re encouraged to take with free reusable bottles—provided to participants with complimentary transit cards—branded with the hashtag “#deMadridydelgrifo” (“From Madrid and from the tap”). The Spanish pavilion—appropriately one of the largest and most prominently displayed—hosted several panels and offered traditional sandwiches and snacks. Various Spanish companies and organizations also set up their own exhibits.

Among the diverse assortment of countries with pavilions are Bangladesh, Qatar, India, Indonesia, Germany, Italy, the Republic of the Congo, Serbia, South Korea, Turkey and Thailand, among several more! Each had something unique to offer—sometimes literally! Germany and Italy offered free coffee. South Korea provided bamboo toothbrushes. Senegal featured several traditional snacks. Turkey had free Turkish delights. Thailand gave a choice between three items—reusable bamboo straws, a keychain, or a tote bag—provided you answered a short survey about their pavilion.

Many pavilions doubled as workspaces for people to meet, rest, or conduct their business. The Serbia pavilion—emblazoned with national colors, imagery, and the charming message of “Serbia Cares”—had tables set up with snacks and a more enclosed office space (with more snacks). South Africa, France, Qatar, and Turkey offered larger open-air spaces where people congregated or worked on their laptops. Hospitality, in varying forms and degrees, was the shared feature and aim.

Several pavilions were heavy on substance as well. Japan’s, one of the larger ones, presented a wide variety of technologies and initiatives—complete with scale models and diagrams—showing the country’s contributions to climate change research and mitigation. Bangladesh, Republic of the Congo, and Thailand had panels rich with data and infographics about their various national programs, initiatives, and achievements. Indonesia and India had among the largest and most intricately designed pavilions, with the latter celebrating Mahatma Gandhi and featuring floor-to-ceiling video screens documenting the country’s landscapes and climate progress.

Suffice it to say, the pavilions speak to the inherently globalized nature of climate change action. It is difficult to tell which stakeholders invested in which pavilions—governments, businesses, nonprofits, or some combination of them all—but it is interesting to consider the motives behind them. Aside from its international character, the climate change campaign is deeply political: That’s to be expected when you’re trying to get 200 countries and territories to agree on a concerted action.

I believe the COP25 pavilions—while fun, charming, and even festive—reflect, to varying degrees, a serious and pragmatic desire to win supporters, connect with potential partners (including other nations), and show the human side of climate change, something that is easy to lose sight of when delegates are negotiating the finer technical details of cap and trade or climate financing.

Dispatch 2

Dec. 2, 2019

An ‘overwhelming and educational’ experience

By Natalie Cavellier

Day one of the COP has been both overwhelming and educational. I realize, however, that I and others have a somewhat limited understanding of what exactly a COP is. After reading Twitter posts directed at the U.S. COP25 delegation leader and speaker of the house, Nancy Pelosi, it is clear that neither do the American people. I thought I’d give a brief overview of what I understand.

COP stands for “Conference of Parties” to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC was signed in 1992 and has been ratified by 197 countries. Under the framework, countries meet every year to assess progress in combating climate change, create agreements, and the various agreements that have resulted from the COPs. COPs began in the 1990s to negotiate the Kyoto protocol and have been focused on the reduction of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions and other climate related issues. Today the COP is focused on negotiating sections of the Paris agreement.

The focus of this particular conference, and the official negotiations, will be on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, and distilling the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Article 6 is intended to operate as a mechanism to reduce emissions through carbon trading and carbon tax. However, I will be following adaptation and sea level rise adaptation measures. Since this is such a broad topic area, I will be narrowing my area of focus during the course of the week. Right now, I could explore various subtopics, but where I decide to focus my time will depend on the speakers and presentations offered.

I should mention that presentations are offered separate of the official negotiations in countries’ pavilions and cover a wide array of topics. This means that attendees have an almost Epcot like experience. Attendees can go from pavilion to pavilion, decorated by different countries accordingly. In this atmosphere, it is hard to choose just one thing to follow. The nature of the conference is overwhelming.

Dispatch 1

Dec. 1, 2019

“We Have Arrived”

By Jessica Owley

It’s Dec. 1, and I have just arrived in Madrid with three students to participate as accredited observers at the international climate change negotiations. This week our students are Romney Manassa, Natalie Cavellier and Gabriela Falla. All three are upper-level law students interested in environmental law and international law. They will have the unique opportunity to see how an international treaty is negotiated and to engage in problem-solving for the greatest problem of our era: climate change.

We are also joined by professor Ileana Porras, an expert on sustainable development and climate change law. The five of us will spend the next week tackling this grand challenge from a law and policy angle. We will be working with NGOs to distill some of the proposed policies while representing UM and sharing some of the work we are doing in Miami. We will be sharing daily updates about the process and what we are learning here.