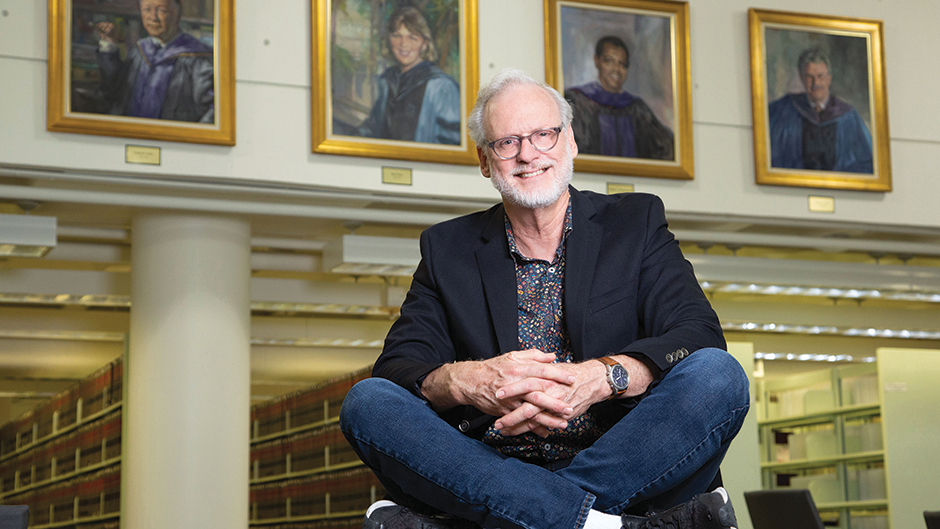

Sit most anywhere in the Miami Law library for a period, and at some point, a specter of continuous motion will enter the scene. Flying along behind a scarred wooden three-shelf wheeled cart, sometimes muttering gleefully, comes a measure of lean and lank, clad in flowery short sleeves, dungarees, and running shoes. If Bill Latham were punctuation, he would be an exclamation point. Italicized.

The 39-year Miami Law circulation librarian (who started off as a circulation staffer) practically arrived in the stacks by chance since he is equally at home in the world of hardbound pulp and interpreting reality with gouache, oil, or acrylic paints on stretched canvases. Of the hundreds of paintings—portraits, landscapes, still lifes—he has created in his six decades of art, four are formal portraits of past deans that hang in The Gail D. Serota J.D. ’79 Reading Room.

From coloring books to art school

Latham was born just 15 crow miles from the law library in Hialeah, when the rural prairie outpost was but home to a spectacular horse racing track. “I could sit on rise across the street and look at a field of wild grass that ran all the way to Miami Springs. It looked like Holland,” he said. “It was gorgeous, with wild winter clouds rolling by. It struck me as very European, and I was 12.

“That is where the world ended,” he said. “Hialeah was like a growth on the back of Miami Beach, where the Beatles and The Supremes visited, and movies were being made. Everything was on Miami Beach. We had a derelict farm and a Dino the Dinosaur [Sinclair] gas station in my neighborhood.”

Latham grew up as the second youngest of six, with ancestral ties to Poland and the great immigration of European Jews to New York, New Jersey, and Miami Beach. “My grandparents lived on Miami Beach. It was like going to another country,” he said. “Nothing ever happened in Hialeah; you could hear a cow screaming in a thunderstorm.”

From the first days of art periods in his neighborhood elementary school’s second grade, Latham was noticed, then nurtured and mentored by the once-a-week art teacher. Sometimes he would get presents of sketch pads or paint sets as a young boy, though truly he was very disappointed when the pads were actually coloring books since it stifled his artistic endeavors.

His gift would grow and be awarded in local school and art shows. He studied the great artists of the generation, admiring the breadth and styles of de Kooning, Rauschenberg, Hockney, and Jasper Johns, and would earn a spot at the legendary Parsons School of Design in New York’s Greenwich Village.

“It would have been a greater experience, if not for the culture shock; I went from the boonies of Hialeah to Manhattan as a 19 year old,” he said. “The work was very hard for me, and I felt like the other kids were making art and I was just overwhelmed.”

Even in the 1970s, Manhattan was beyond the financial reach of his family and Latham lived in the Chelsea YMCA, among low wage workers. (A cab driver dying of consumption lived in the room next door.) His fourth cousin Sylvia of Jackson Heights or Aunt Pearl of Coney Island would feed him now and again.

“Then my grandfather died, who was my one champion throughout my life,” he said, “and I had to experience it alone. It was just too much, and I left after one semester.”

Latham transferred to Florida State University in Tallahassee to finish his degree before moving to Brooklyn several years later with two friends to try to crack into the art gallery track. He had some successes—group shows and print publications. To help support himself and keep him in turpentine, canvas, and paint, he worked in the library of Pace University, near the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, and thus began his life among the stacks.

Family, and the pursuit of a Master of Fine Art at UM, would bring him back to South Florida and, again, the library would factor in financially. He took a library job at Miami Law while waiting to be accepted in the MFA program then juggled classes, working as a teaching assistant for two years. After graduation, Latham taught college art all around Miami and moonlighted at Miami Law.

In the late 1980s, Latham’s mother’s health took a turn for the worse and he spent more time caring for her, which gave him much more time to paint. Soon after his mother’s death in 1989, he had four shows of his work and was well on his way to establishing himself more widely.

“Around the same time a full-time job opened at the library, and I needed a dependable way to support myself, so I took the job,” he said. Offers of shows and commissions went unanswered because of lack of time to produce a body of work. “I spent six months curating a show at the Wolfson—it is a huge investment of time—and it was only half-good, a B+ at best.”

Hurricane Andrew in 1992 wiped out many of Latham’s paintings that were being stored at a brother’s house in Homestead, dividing his art and work life even further.

“What I am grateful for and why I don’t think I have regrets is when my art life creeps up, it’s only in a positive way,” he said. “I have a friend in the banking world with many patrons of the arts friends. The friend was one of my early models for a series of paintings with light and water. He saw one of the paintings at the home of an art collector acquaintance, and, when asked, the man responded that it was the work of a very important local artist.”

Latham’s post-Miami Law phase is not even a work in progress. “Seriously, I never thought I would live this long!” he said. “I would like to finish an illustrated children’s book I started in my 30s. If I do retire, I’ll probably move to Tallahassee where my brother has a wannabe farm with four chickens and an armadillo. Maybe I’ll paint large canvases of neighborhood cows,” though he said such a move would be if circumstances favor such a plan.

“But seriously, I want to express my gratitude for working where I am working,” he said, “or I wouldn’t have stayed so long. The students are so interesting, so funny, they are so smart—they catch on right away. And if they are not dying from no sleep—or anything else in their lives—let’s just say I couldn’t work in a back room. Well, I could but I would have been gone in a month.”

Read more Miami Law magazine stories.