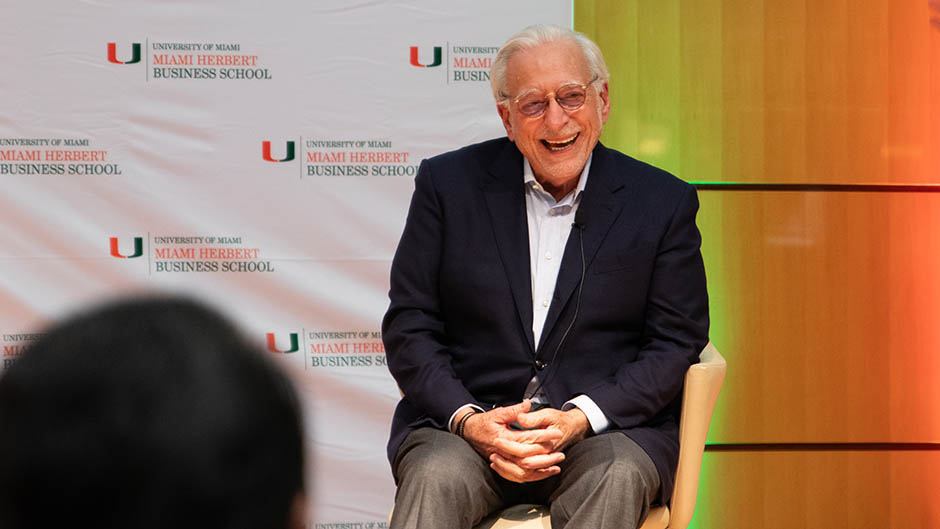

It was only fitting that during his visit to Storer Auditorium as a guest of the Patti and Allan Herbert Business School at the University of Miami's Distinguished Leaders Lecturer Series, Nelson Peltz candidly addressed the most conspicuous aspects of his career.

“I don’t want you all to take lessons from what I’m going to tell you,” Peltz cautioned students who’d braved a rainstorm last Thursday evening to hear the legendary businessman and operational activist investor. “The Dean [Ann M. Olazabal] is not thrilled about this, but I went to Wharton and I had a wonderful time in my short period there.”

“I just didn’t get to class that much and, when I did get to class, I couldn’t figure out when I was going to use accounting and finance and economics,” Peltz, 81, said as he matter-of-factly explained why he dropped out of Wharton’s undergraduate program. “I was way too immature to be in a place like that.”

Peltz demonstrated that he is not only an unparalleled businessman but also a captivating storyteller, who enjoys discussing Corporate America and life, interspersed with humor and insight. Peltz’s appearance was interspersed with mirthful comments from event moderator Stuart Miller, chair of the UHealth board and a member of the University’s board of trustees, and executive chairman and co-chief executive officer of the Lennar Corporation.

Miller laughingly recounted how he and Peltz once traveled to Naples, FL to lunch with the CEO of a company Miller wanted to buy. “‘I know the CEO, he’s a very, very nice man,” Miller recalled advising Peltz, who’s 15 years Miller’s senior. “‘Let’s start with some niceties, let’s let the conversation develop and mature, and then we’ll migrate to a more serious conversation and discussion.’”

Well, “before the bread hit the table, Nelson announced, with this overwhelming presence and his strong, self-assured voice: ‘We want to buy your company, we think it’s going to be a good deal for you, we think it’s going to be a good deal for your shareholders, and it’s going to be a good deal for us as well. Whaddaya think?’”

“So much for niceties,” Miller chuckled, shaking his head over the bargaining tactics of a man he considers a treasured friend.

The Brooklyn-born Peltz said that after leaving Wharton, he spent time skiing in Maine, while working as a dishwasher to support himself. “You gotta plan ahead, you see?” Peltz said of those carefree days in Maine. “And eventually the snow melted, which I didn’t plan on.

“My dad had a very small, but nicely profitable, food produce business,” Peltz said. “It supported our family nicely. I asked him for a job driving one of his trucks, 100 bucks a week for two weeks. And he said, yes—if I shaved my beard off.”

After spending a portion of 1963 maneuvering A. Peltz & Sons frozen-food distribution trucks through New York City’s hectic byways and boulevards, Peltz joined the brain trust of his father’s company, along with Peltz’s older brother, Robert Peltz.

Peltz quickly found himself saying, “‘Dad, there are a lot of [business] opportunities we’re missing here.’ He said, `Why don’t you stay for a year and address them?’ Which I did. And basically, in very short order he threw the keys to the family company on the table and said, ‘Go fetch!’”

“We built that $2-million-dollar business into almost a $150-million-dollar-a-year business…I learned very early on that cash flow is the most important thing there is. There’s nothing like cash flow, and that’s what counts in business.”

In 1972, he merged A. Peltz & Sons with Flagstaff Foods to form Flagstaff Food Service, together with Peter May who became Peltz’s long-term business partner.

In 1983, Peltz and May acquired a stake in Triangle Industries. Peltz became the chairman, CEO, and a director of Triangle, which was valued around $80 million in 1983. Thanks to a series of spectacular corporate acquisitions and operational improvements, Peltz and May transformed Triangle into the world’s largest packaging company, and a member of the Fortune 100, before selling Triangle to French conglomerate Pechiney, S.A., for almost $1 billion in 1988.

Presently the non-executive chairman of The Wendy’s Company and a director of Unilever PLC, from 1993 to 2007, Peltz was chairman and CEO of Triarc Companies, which owned the Arby’s Restaurant Group, Inc., and the Snapple Beverage Group, among other holdings, during Peltz’s stewardship.

Peltz’s extensive business accomplishments, including his role as an operational activist investor, are far-reaching and diversified, highlighting his multifaceted approach to both business and life.

Peltz is not merely a business savant; he’s also a parent to 10 children, ranging in age from 20 to 40, gaining invaluable insights from each one of them.

“I want to tell you something -- I learn so much from my kids. So much!” Peltz stated joyously. “They don’t even know how much they teach me. I’m 81 years old. I have friends who are 81 years old and they go to dinner at 4:30 in the afternoon, okay? I’m not kidding you!

“Maybe 5, if they want to have a late night,” Peltz added, prompting another wave of Storer Auditorium laughter.

“I sat up with two of my kids and one of their friends last night till 1:30 in the morning. Just talking. Do you know how much you could learn from talking? One was 30, one was 20 and their friend was 35. We talked for three or four hours.

“I can learn what products they use, I can learn what they’re thinking about, their concerns, the opportunities they see,” a smiling Peltz observed. “It’s amazing what I get from all of my kids . . . so I want you to know that I have all these kids for business reasons!”

That joke wasn’t lost on Gregory Faulkner, a Miami Herbert junior majoring in finance and accounting. But Faulkner’s takeaway went beyond humor.

“I thought it was quite interesting that he mentioned how much he has learned from youth,” said Faulkner, a Naples native looking to start a Florida insurance brokerage business after graduation. “Anyone you have a conversation with can add value and create intellect. I think that not writing people off is what separates the successful from the extremely successful.”

Making Nelson Peltz a rare orator who gets high marks for being a good listener. His knack for generating straight-no-chaser commentary was pretty much a foregone conclusion.