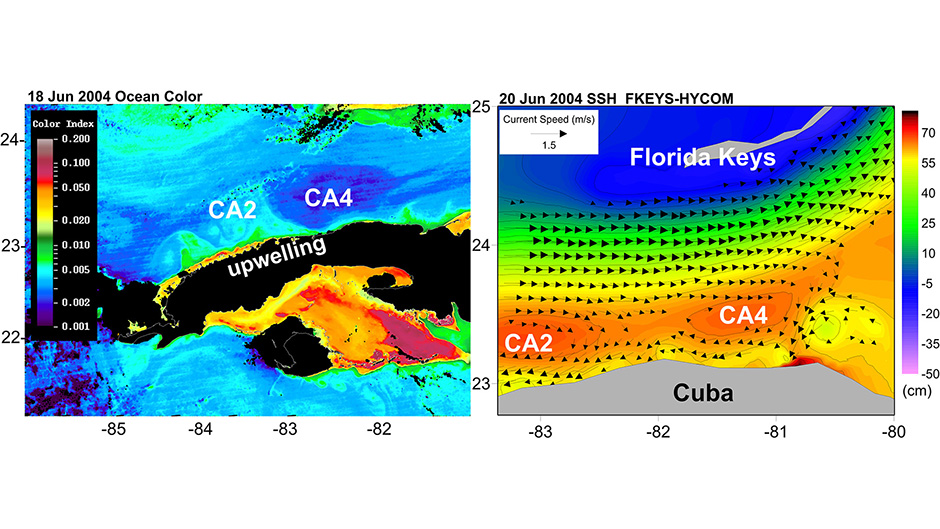

MIAMI—A new oceanographic study underscores the deep connection that exists between Florida and Cuba. Researchers at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science have uncovered specific types of previously unknown clockwise recirculating ocean features (called anticyclonic eddies or anticyclones), which they named Cuban Anticyclones, or CubANs since they form and travel eastward along the Cuban coast. These features enhance the knowledge about the Gulf Stream (called Florida Current within the Straits of Florida), and the connectivity between South Florida and Cuba.

Located near some of the most pristine coral reefs in the world, researchers believe that CubANs may play an important role in navigation in the region, as well as the transport of materials, from coral and fish larvae to contaminates from potential oil spills in Cuban waters. As these clock-wise eddies travel south of the Florida Current, they work in synergy with the well-known counter-clockwise eddies to the north of the Florida Current, along the Florida Keys. This double action of eddies greatly enhances the meandering of the powerful oceanic current, a pattern that brings it at times close to the Florida Keys and at other times near the Cuban coast, creating corridors of connectivity across the Straits of Florida.

The ability to predict these corridors is important for navigation, fisheries and pollution control. The study has also revealed the importance of predicting pools of cold waters that reach the surface near the Cuban coast and reefs due to the so-called “upwelling” that winds generate. These pools separate the warm CubAN eddies and are paramount to their evolution.

Using an ocean model developed in Vassiliki Kourafalou’s Coastal Modeling Lab at the UM Rosenstiel School that provides a seven-day forecast of ocean properties, in tandem with satellite and field observations, the research team was able to identify the Cuban eddies and analyze their circulation patterns along the northern Cuban coast for the first time.

“The study has shown that there are many ways in which South Florida and Cuba are connected or separated and these conditions vary rapidly from weeks or even days and hours apart,” said the study’s lead author Vassiliki Kourafalou, a research professor of ocean sciences at the UM Rosenstiel School. She added that “the health of our South Florida reefs and coasts can be potentially influenced by Cuba’s coastal environment through the ocean currents and their naturally changing patterns”.

The same forecast model, known as Florida Straits, South Florida and Florida Keys Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model (FKEYS-HYCOM), supported marathon swimmer Dianne Nyad’s successful crossing from Havana to Key West in 2013. In a previous, unsuccessful attempt, Nyad had started the crossing while a CubAN eddy was present, which created strong currents against her.

The study, titled “The Dynamics of Cuba Anticyclones (CubANs) and Interaction with the Loop Current/Florida Current System,” was published in the October 2017 issue of Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. The study’s authors include: Vassiliki Kourafalou, Yannis Androulidakis, and HeeSook Kang from the UM Rosenstiel School and Matthieu Le Hénaff from the UM-based Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies and NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory in Miami.

The research was made possible in part by a grant from The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (award GOMA 23160700), and in part by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RESTORE Act Science Program (award NA15NOS4510226) to the University of Miami.