Turning a powerful lens on his own profession, public health thought leader Sandro Galea, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H., an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, headlined National Public Health Week at the University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies.

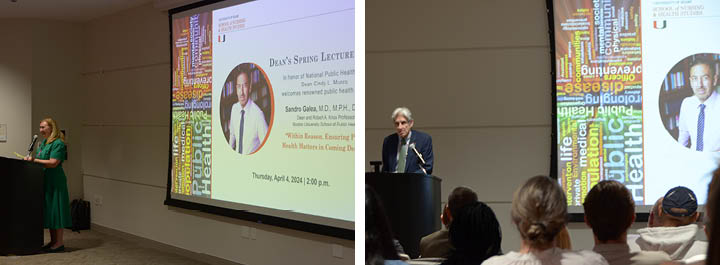

Dr. Galea, the dean and Robert A. Knox Professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, delivered an address titled, “Within Reason: Ensuring Public Health Matters in Coming Decades,” as part of the School’s Spring 2024 Dean’s Lecture Series. Galea’s lecture was based on his 24th book, Within Reason: A Liberal Public Health for an Illiberal Time, published by University of Chicago Press in 2023.

SONHS Dean and Professor Cindy L. Munro welcomed students, faculty, and University guests to the S.H.A.R.E.® Auditorium on April 4, and highlighted the importance of National Public Health Week. UM Provost Willy Prado recognized Galea as one of his “public health heroes,” while UM President Julio Frenk, a fellow public health expert, described his longtime colleague and friend Galea as “a public intellectual” and “an incredibly prolific writer” whose widely cited research “not only enriches academic discourse but informs policy and public understanding.”

Galea’s book “examines the tumultuous interplay of politics and public health during the COVID-19 pandemic, advocating for a future where public health is guided by critical, open inquiry,” President Frenk said of Within Reason. “Let us commit to embracing the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead with openness, curiosity, and a steadfast belief in the power of reasoned and respectful debate to effect meaningful change.”

Galea said for meaningful change to take place, serious discussions about COVID-19, “the sentinel health tragedy of our time,” are still needed. “Certainly we do a disservice to the tragedy of the lives lost if we do not think about what happened and why,” said Galea, an epidemiologist and physician who studies behavioral health consequences of trauma. “It is important, now that we are past some of the highly emotive phase of COVID, to really reflect and say, ‘how did we do, what did we do?’ Not for the sake of finger-pointing and looking back, but for the sake of learning and looking forward.”

During a talk punctuated by data-rich infographics and historical anecdotes, Galea advocated for a public health that is “liberal” in the sense of being open to new ideas and “willing to respect or accept behavior or opinions different from one’s own.” If we define health not simply as the absence of disease, but as “a means to live a full, richly realized life,” he said, “that becomes a real issue when we talk about some things we learned during COVID.”

When COVID hit, health was already deeply unequally distributed, noted Galea. In addition to underlying structural inequities and pre-existing poor health, there was a “disinvestment in what could have helped,” he said. “We have been shrinking the public health workforce for the past 20 years.”

An early misstep in public health communication related to efforts to hamper virus transmission by instructing those who could to work remotely, said Galea. He argued that this was equivalent to telling the public: “Because there is a scary novel virus circulating, we are going to protect the people who make more money at the expense of the people who make less money.”

So, why would a well-informed, well-intentioned public health sector promote such a message? “Underlying structural inequities are so profound that in many cases we missed them,” said Galea.

The result was predictable, he added. “The people who died in the first year of COVID were construction workers, cooks, janitors, retail workers,” he said. These frontline workers were disproportionately people of color, Black Americans, who also suffered disproportionately higher rates of underlying disease burden, i.e., higher vulnerability to severe impacts from COVID.

He said “false certitude, contradiction without acknowledgment, and intolerance of disagreement” compounded public health failures during COVID. “Before COVID nobody could even pronounce epidemiologist,” he quipped. With the celebration of the profession came an overconfidence that was difficult to overcome. Further, there was a failure to acknowledge when seemingly contradictory messages were being relayed.

“We communicated again and again and again things that were fundamentally wrong. There’s tremendous uncertainty in our models, but that’s not how we communicated,” he said. “With a lot at stake, it is important to be humble.”

Intolerance, continued Galea, was “perhaps the worst of our sins” in public health. “We quickly developed an orthodoxy, and we did not allow a plurality of voices.” Public health officials “very clearly aligned with one particular perspective, which was essentially anything short of schools being completely safe was unacceptable,” he said. While all students fell behind, minority and low-income students experienced a significantly greater impact from school shut-downs. “We know there is perhaps nothing more important for long-term health than education.”

Despite some pandemic-era wins, like rapid development of an extremely effective vaccine, health gaps and inequities widened dramatically, and trust in public health agencies like the CDC eroded almost uniformly across all groups, particularly among young people.

“What I’ve been trying to do is to encourage us to have those difficult discussions by creating the framework for those difficult discussions,” Galea explained. The way forward, he urged, is “epistemic humility, radical compassion, and reform through reason.”

“Radical compassion” means keeping other people in mind, understanding how public health decisions affect the “other,” he said. For instance, although more people under 65 died of drug overdose than COVID during the first few years of the pandemic, there was no “overdose ticker” promoted by the media.

“Dealing with health inequity is part and parcel of the business of dealing with health, and we need to think of it that way, always, as intertwined,” he added. “Health equity means making sure everybody has equitable access to health, that people are not unfairly denied health.”

Reforming public health demands that we commit to reason and “divorce ourselves from our ideological affiliations,” said Galea. He offered the example of pioneering physician Ignaz Semelweiss, who in Vienna in the 1850s figured out that hand-washing was key to reducing maternal mortality rates caused by postpartum infection. It may seem common sense now, but back when Semelweiss put the patriarchal power structure, his hospital, on notice that its physicians were dirty-handed death culprits going straight from conducting autopsies to delivering babies, while nurses were sanitizing their hands with positive outcomes, it did not go well for Semelweiss or for the women his groundbreaking-but-rejected discovery could have saved.

While human life expectancy has doubled overall in the past 150-200 years, said Galea, the “world remains a terrible place for health for many people.” Public health is “about how we structure our world so that health is better for all of us, not just some of us,” he said. “There’s a lot more we can do and should do.”

During his UM visit, Dr. Galea spent time meeting with SONHS public health and Ph.D. in Nursing Science students and their faculty.