Nearly 40 years later, Tim Huebner still remembers the extensive course syllabus that University of Miami professor Whittington Johnson handed out to students on the first day of his Early National U.S. History class. The size of a pamphlet several pages long; it was chock-full of reading assignments, exam dates, and deadlines for research papers.

“It definitely had an impact,” Huebner recalled of that fall semester day of his junior year. “There were maybe 20 to 25 students in class. But on the second day of class, it was significantly lower.”

Realizing that the syllabus was not intended to intimidate but to inspire, Huebner stuck with the class. “Dr. Johnson had high expectations for us and cared deeply about the subject matter,” Huebner said. “For that entire semester, he took a personal interest in each of us, and eventually, he became a person I wanted to emulate.”

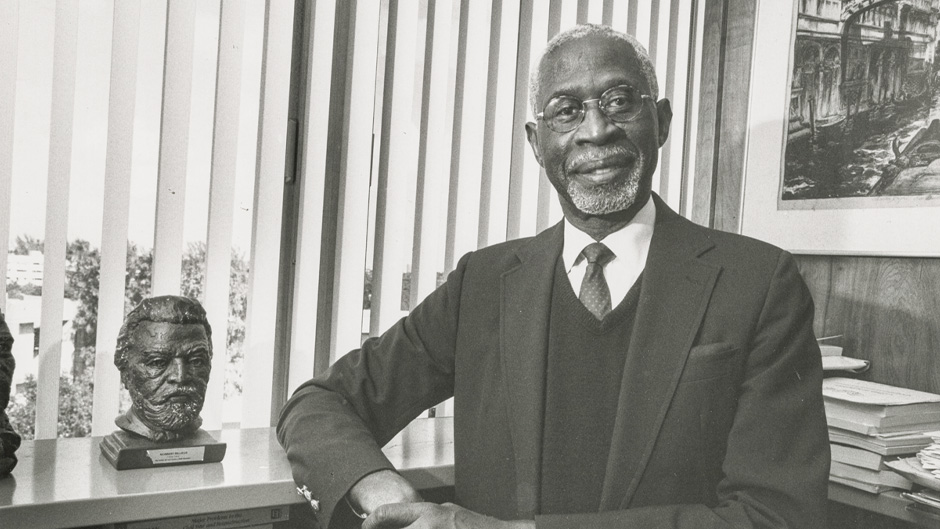

Johnson, the University of Miami’s first Black tenured professor who—over an illustrious 32-year career at the institution inspired thousands of students, teaching history courses that ranged from the American Revolution to the African diaspora and conducting research in areas such as race relations in the Bahamas—passed away on Nov. 1.

He was 93.

“A great and compassionate leader, the heart and soul of what would become a great university” is how Distinguished Professor of History Donald Spivey, who knew Johnson for more than 30 years, described his former colleague. “As the first Black faculty member at the University, Whitt, as we called him, faced tremendous pressure. But he rose to the occasion.”

At a recent memorial service for Johnson held at Liberty City’s Church of the Incarnation, where Johnson was a longtime member, Spivey recalled how the late professor led a contingent of Department of History faculty members who won several teaching and research awards during the early 1990s. “We felt like the Dallas Cowboys of college history departments across the nation, and Whitt was our leader,” said Spivey, referring the NFL team that captured three Super Bowl titles during that time.

Professor of sociology Marvin Dawkins remembers Johnson as a “consummate professional.”

“We first met in 1988, when he served on the search committee that invited me to the University as a candidate to direct what was then called the Caribbean, African, and African American Studies Program,” Dawkins said. “We became colleagues and friends from that time until his transition. I rarely saw Whitt not wearing what I called his ‘uniform,’ a sports jacket and tie. He was no-nonsense when it came to his research and teaching on the history and culture of the Bahamas.”

Robin Bachin, the Charlton W. Tebeau Associate Professor of History, first crossed paths with Johnson in the winter of 1996, when, as a recent Ph.D. graduate, she interviewed for a tenured faculty position in the Department of History. “Incredibly cordial, with a captivating smile and easy-going demeanor,” Bachin recalled of Johnson. “He helped put me at ease and calm the nerves of a grad student participating in her first on-campus job interview.”

One semester, Bachin had to teach Johnson’s American Revolution class after he had a medical emergency. “I was concerned about teaching the class since my teaching and research focus is on 20th-century U.S. history. Whitt told me that sometimes it’s easier to teach subjects that aren’t, in fact, directly related to our research interests because we have an easier time conveying the most important aspects of the historical moment rather than being too caught up in the various arguments scholars have made about how to interpret issues and events. I found that advice liberating and took it to heart not just for the American Revolution class but for my teaching overall,” she remembered.

“He was a great scholar and leader during difficult times,” professor of history Edmund Abaka said of Johnson. “He exemplified collegiality and community and department citizenship. For me, he was a bastion of hope and stability in a difficult adjustment period at the University.”

Johnson’s students often called him Dr. J. “He was one of the most brilliant minds I’ve ever met,” said former student Peter Ariz, who became an attorney at Johnson’s urging.

Whittington Bernard Johnson was born on April 29, 1931, in Miami, Florida, the son of a mattress maker father and domestic worker mother from the Bahamas.

He graduated from Miami’s historic Booker T. Washington High School in 1949, going on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees from West Virginia State College and Indiana University, respectively.

During Johnson’s Ph.D. studies at the University of Georgia, the civil rights movement in the United States was still at its height. It was then that he realized Black scholars were needed “to tell the Black story.”

“I wanted to look at more than just the Black experience in America, but the African diaspora from a wider perspective,” Johnson once said.

His storied teaching and research career at the University of Miami began in 1970—a time, according to Bachin, during which calls reverberated across the nation for higher education to rethink its curriculum and include the voices of groups that had historically been silenced, including people of color, women, and the LGBTQ community.

“Hiring faculty of color was an important contribution to the effort in higher education to better reflect the diversity of the American population and its experiences,” she said. “Like other trailblazers, Whitt would have had to walk a fine line between being accepted into an established higher education culture and trying to open new opportunities for enhancing faculty, curricular, and student diversity. His qualities of grace and collegiality certainly aided in this process.”

As a faculty member at the University during those early years, Johnson flawlessly juggled a daunting schedule—from serving as a role model for Black students to speaking at events of historical importance to that community to being a productive scholar in his department, said Dawkins, noting that Johnson’s research endeavors were especially stellar.

From the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., to the British Library in London, to the Bahama Islands, Johnson traveled the world to conduct his seminal research, always cognizant of history’s immense importance. “Think about a person who has amnesia, and then multiply that in terms of a community or a country. That’s the importance of history in a nutshell,” Johnson once said. “It enables us to keep our memory of past events so that they can be interpreted from generation to generation. Not having a memory is almost as bad as letting someone else write your history.”

A three-time chair of the Department of History, Johnson received numerous awards, including the College of Arts and Sciences’ Outstanding Professor Award. He is the author of “The Promising Years, 1750-1830: The Emergence of Black Labor and Business”; “Black Savannah, 1788–1864,” which examines the Black community of Savannah, Georgia, during the antebellum and Civil War periods; and “Race Relations in the Bahamas, 1784-1834: The Nonviolent Transformation from a Slave to a Free Society.”

Johnson retired from the University in 2002.

As for Huebner, who is now a professor of history at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, he continues to honor Johnson for the profound impact he had on his life.

“Dr. Johnson would walk into the classroom on the first day of class, a tall, dark man wearing a solid green suit,” Huebner said. “He explained that he wore a green suit on the first day of class because green means go. Well, I don’t have a green suit, but on the first day of classes, I always wear a green tie in his honor.”