Toward the end of Traci Ardren’s Anthropology of Food class, students receive an unusual assignment: they are asked to tell the story of their life through recipes.

“It was definitely one of the most dynamic and fun homework assignments I’ve ever had,” said Isabella Arosemena, a senior majoring in environmental science and policy who took the course in the fall. “I was thinking about recipes that were integral to my childhood or just to me as a person, recipes that were my first time cooking by myself or that I adapted to fit more with my lifestyle.”

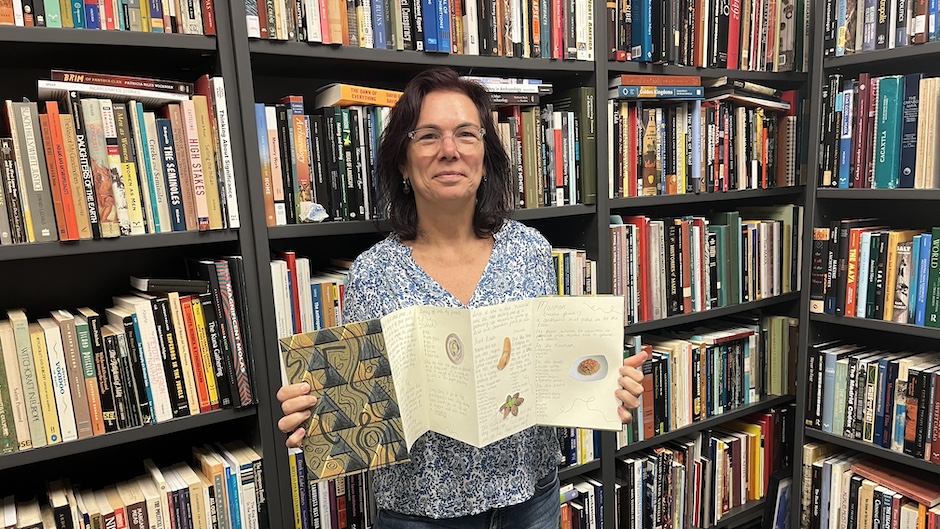

This is precisely the kind of reflection about food and identity that Ardren, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the College of Arts and Sciences, hopes to inspire with the cookbook assignment.

“I ask them to tell the story of who they are through 10 recipes,” she said. “I really appreciate that the students take this assignment seriously. It’s a powerful sort of lens.”

The cookbooks provide a window into not only the experiences of Ardren’s students, but also the diversity at the University of Miami. When Ardren taught the course in the fall, one of her students created a cookbook showcasing both Polish and Indian recipes. Other cookbooks shared recipes from Syria and Lebanon, the southern United States, different parts of Latin America, and Jewish holiday traditions. To accompany each recipe, the students wrote a paragraph about why they chose that dish.

“I think it’s a very tangible way to see how diverse the campus is,” Ardren said.

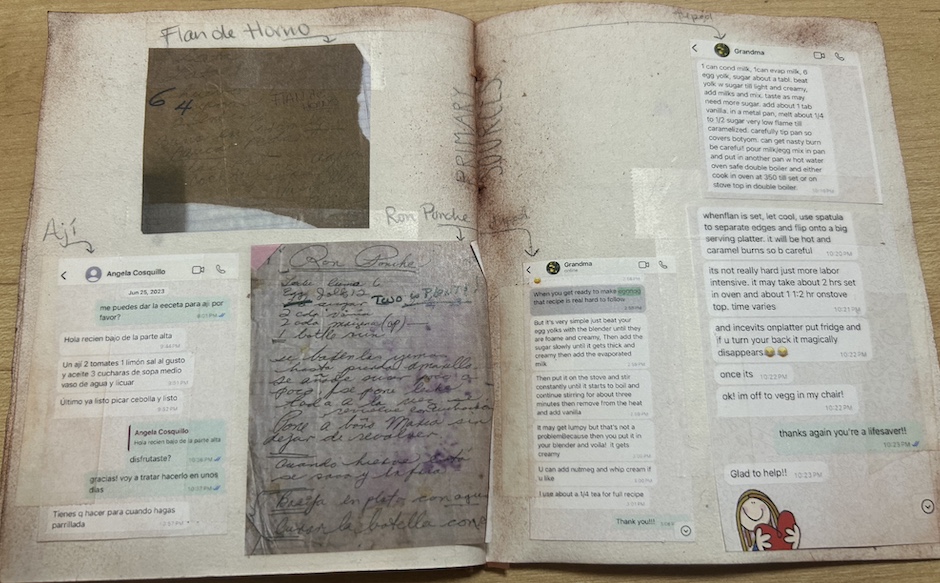

Arosemena, whose family is Panamanian, included her mother’s ceviche recipe in her cookbook, along with recipes shared by her grandmother. Among them was her great-great-grandmother’s instructions for making ron ponche, which is similar to eggnog and which the family makes every year at Christmastime. Arosemena’s grandmother sent her a photo of the recipe, which was written in her great-great-grandmother’s handwriting on “a really old, weathered piece of paper.”

Other recipes in Arosemena’s cookbook reflect more recent life experiences. She included a spicy ahí sauce her host family made when she studied abroad in Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands, as well as a chili recipe she adapted to make it vegetarian when she stopped eating meat in college.

Arosemena said the most challenging part of the assignment was getting recipes from her mother, who cooks from memory and doesn’t measure ingredients. For her mother’s recipes, Arosemena included the proportions for the ingredients instead of exact measurements.

In addition to exploring their families’ food traditions, students visit a historic cookbook collection in Special Collections in the University libraries to conduct research for the assignment. The Anthropology of Food class also examines broader issues related to food, identity, and culture. The course covers everything from the types of things humans evolved to eat to the role cookbooks have played in creating national identities.

“We talk about race and food, we talk about gender and food, and we move eventually into nationality or nation-making,” Ardren said. “There’s a lot of scholarship on the role of cookbooks in creating a national identity. When India became an independent country, one of the things it did was bring all these different regional cultures together under an umbrella, and cookbooks have been used to help that process.”

Students also complete an assignment that involves experiencing and writing about a food culture with which they are unfamiliar. Arosemena chose to learn about Russian food because she has a Russian roommate.

“I’d never had Russian food. I’d never really thought about trying it,” she said. “We went to a Russian restaurant, and it was a really wonderful experience. I’m grateful for that experience and for learning as much as I could about the culture.”

At the end of the course, students can choose to donate their cookbooks to Special Collections.

Arosemena decided to donate her cookbook and also share it with family members. With help from one of her sisters, she handmade copies of the cookbook to give to another sister and to her grandmother as Christmas and birthday presents.