When Morgan Threatt was born, one of her baby gifts was a chest emblazoned with the words “Future Delta.” It became a permanent fixture in her bedroom growing up.

Now, the senior broadcast journalism major is president of the University of Miami’s chapter of Delta Sigma Theta—the same sorority her mother joined nearly 30 years ago and one of the “divine nine” Black Greek Letter Organizations (BGLOs) that have a rich history of celebrating Black culture, advocating for social justice, and elevating the voices of Black college students and graduates throughout the nation.

“I remember that my mom’s sorority sisters were there for all major events in my life,” said Threatt, who is also the founding president of the University’s chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists. “This isn’t just a group you join for four years and then never talk to these people again.”

The first BGLO was Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, founded in 1906 at Cornell University as a study and support group for minority students who faced educational and social prejudice. Between 1908 and 1922, two additional fraternities and three sororities, including Delta Sigma Theta, were established at Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C. Others formed at Indiana University, Butler University, and Morgan State University, and today all nine are part of the National Pan-Hellenic Council, established at Howard in 1930 as the umbrella organization for BGLOs.

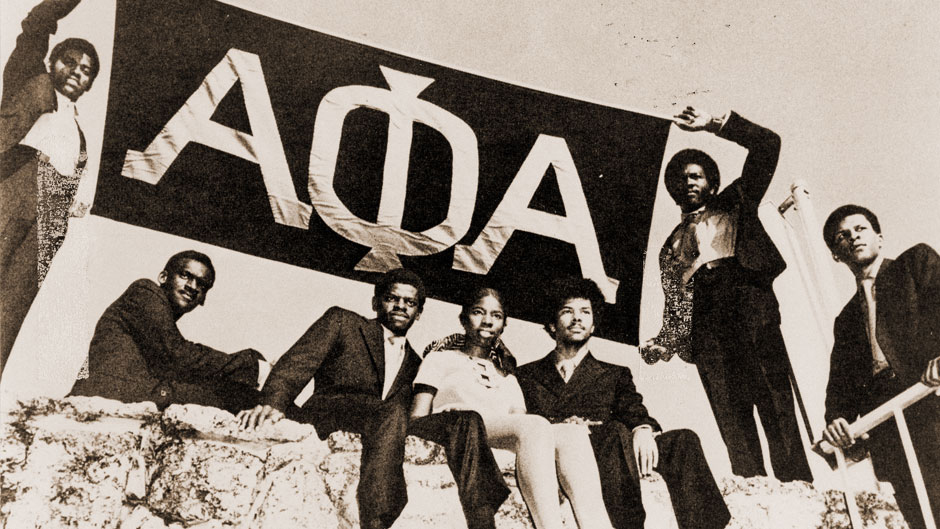

Alpha Phi Alpha was also the first BGLO at the University of Miami, chartered in 1970, just nine years after the University’s desegregation and only three years after United Black Students was a formally recognized campus group. Today, there are six active BGLOs at the University—three fraternities and three sororities with about 50 student members combined.

“Historically, these organizations bonded around student engagement for their communities,” said Anthoney Kinney, assistant dean of students and adviser for the National Pan-Hellenic Council at the University of Miami. “They were all college students, but they weren’t isolated from what was happening in America—racial prejudice, social segregation, economic and academic disenfranchisement.”

Greek organizations today typically have a commitment to service. But BGLOs place service above socialization as their primary focus. “Because of our history and how we were founded, service is at the core of what we do.” Kinney said.

“There’s a different need for these organizations to exist,” said Winston Warrior, a double alumnus and executive director for strategic communications, marketing, and operations in the School of Education and Human Development, and the polemarch, or president, of the alumni chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity that oversees the University of Miami and Florida International University student chapters. Warrior also is a former United Black Students president and Student Government vice president.

“The philanthropies we support are about mentoring, pulling younger people out of difficult situations, raising money for families,” Warrior continued. “We mentor young black men who are in middle school or high school so we can try to break the cycle—get them to be viable, productive citizens and make sure they don’t get killed. It dovetails into why we’re committed to being part of the organization for our lifetime.”

The pursuit of racial justice is in the fabric of BGLOs, and Kinney said that following the killing of George Floyd, University of Miami BGLOs have taken the lead in organizing open discussions within Greek life about race-related issues. Several BGLO members also recently joined other Black student leaders in drafting a letter to University leadership with recommendations for enhancing diversity and inclusion on campus. The University responded to student concerns with a 15-point plan to support racial equality, inclusion, and justice across the University and South Florida.

“You can’t expect change without educating people, and you can’t expect people to be educated overnight,” said Threatt, who lists intergroup dialog as one of her goals as president. “I can’t sit here and say, ‘Why is nobody co-programming with us?’ It’s important for all of us to get together and talk it out, and it’s our duty as BGLOs to reach out. That’s how we start mending the gap.”

For alumna Astin Hayes, who co-founded the University’s Delta Sigma Theta chapter in 2004 and served as vice president of United Black Students, being a Black student leader helped her develop a strong sense of community at the U. It also helped shape her as an outspoken professional, which serves her well as a key account manager for the French spirits group Rémy Cointreau and as the inventor of TipOff, a gaming app in which players guess words related to Black culture.

“In my industry, often I am the only person of color and sometimes the only woman,” Hayes said. “Right after George Floyd was killed and the protests began, I wrote an email to my HR department about how I think the company is great but from a diversity perspective, there’s a lot more we can do to be better. Immediately I got a call back, and now I’m one of the leads on a task force that’s creating pillars for talent recruitment and diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Kinney noted that learning to be outspoken on social justice issues is one of the most profound ways BGLOs transform Black students on campus.

“What I see over and over is the growth that takes place, starting with that education in the history of their organization,” Kinney says. “Through that process, students find a community within the UM community. In my area of student life, we know that involvement is vitally important to students finding a home here and growing and developing. I see them growing as individuals, as leaders, and I see them find a voice, perhaps a voice they hadn’t felt they had before.”

Hayes, who remains engaged with the University as secretary of the Black Alumni Society and through Delta Sigma Theta, is among a vast network of BGLO members who pave the way for future generations to carry on and create new traditions.

Alumnus Antonio Junior, who founded the University’s Kappa Alpha Psi chapter in 1979 with two other students, recalls the small group’s first step show on campus. It was a big move for him, a shy kid from Chicago who had never been on an airplane before coming to Miami. Becoming a Kappa really molded Junior, now an entrepreneur and founder of a fuel-reclamation company.

“We had our white tuxedoes and our canes, and we advertised on campus that we were having this big production,” said Junior. “We didn’t have the shimmy back then. That’s the new thing. It progressed over the years; now all the Kappas do the shimmy.”

Stepping, one of the most visible and celebrated BGLO traditions, is one way for organizations to try to prove they “run the yard.” In friendly competition, they showcase their stroll (their choreographed movement in a line). And in the case of the Kappas, their shimmy (a signature shoulder roll), to gain respect on campus and further deepen their organizational pride and unity.

If your step show is really fresh, you might wind up on a BGLO culture website called Watch the Yard. And if you’re ever in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., you’ll see a photo of Warrior and two fellow Kappas performing in a step show in the early 1990s.

The probate ceremony, which is the presentation of new members to the campus community, is another time-honored BGLO tradition.

“It’s where we say, ‘You might know me as Morgan, but in the world of Delta, you’ll know me as Halo,’ ” Threatt said. “Halo is the name the women who came before me chose for me, based on them getting to know me and the values I have.”

For Threatt, teaching new members of Delta Sigma Theta about the organization’s history and traditions is one of the most rewarding elements of the sisterhood continuum.

“Everyone who has come through my chapter before me has been a mentor for me,” Threatt said. “When you are able to say, ‘My sorority was founded in 1913, and there are hundreds of thousands of women who have come before me who have done XYZ,’ it’s very empowering,” she added. “Being able to have a concrete example of people who look like you, who’ve done some amazing things, and who wear the same letters around their chest—it’s a pride thing.”