A great deal of music education research has looked at whether learning to sing or play an instrument can help children learn or with other kinds of achievement.

But this fall, students from the Frost School of Music's music education program have been working on a study with children in Little Havana to investigate a much more elemental and human question: Does singing make children feel happier and better?

“Much research has examined the relationship between music education and intelligence and academic achievement,” says Carlos Abril, professor of music education and associate dean of research at the Frost School, who is supervising the study with School of Education and Human Development professor Dina Birman. “But we don’t know as much about the relationship between music learning and well-being. It’s not something that’s been on the radar of music education researchers in the past.”

The Miami study is one of four research sites in the Music for Childhood Well-Being Initiative (MCWI), created and led by a team of music education and medical experts at Chicago’s Northwestern University. The other three sites are in Chicago, Mexico City, and York, England. As social isolation, political upheaval, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other issues have caused children’s stress and anxiety to rise worldwide, the MCWI aims to determine whether singing and breathwork can help counter that by improving children’s health and state of mind.

“Our research aims to establish a robust body of evidence supporting the notion that singing together can have a positive impact on children around the world,” Northwestern associate professor of music education and MCWI co-director Sarah Bartolome told Northwestern’s news site Fanfare.

That idea is a potent one for the Frost School students working on MCWI here.

“This study focuses on how music can help you feel, and not to justify using music to help you improve in other areas,” says Rowan Kloss, a music education senior who is one of three undergraduates working on the study.

The Frost School was chosen because of its strong reputation in music education research and service to immigrant, Latino, and underserved communities through the Donna E. Shalala MusicReach program. Abril agreed to participate in the study after speaking to a colleague from Northwestern University about the project. The Miami study site is embedded in MusicReach, a music and mentoring program for economically disadvantaged youth, and was conducted at the Little Havana Leadership Learning Center, an afterschool and summer program that is one of MusicReach’s regular outreach sites.

“I thought it would be a great learning opportunity for our undergraduate music education students to see how research works and to be involved hands-on,” says Abril.

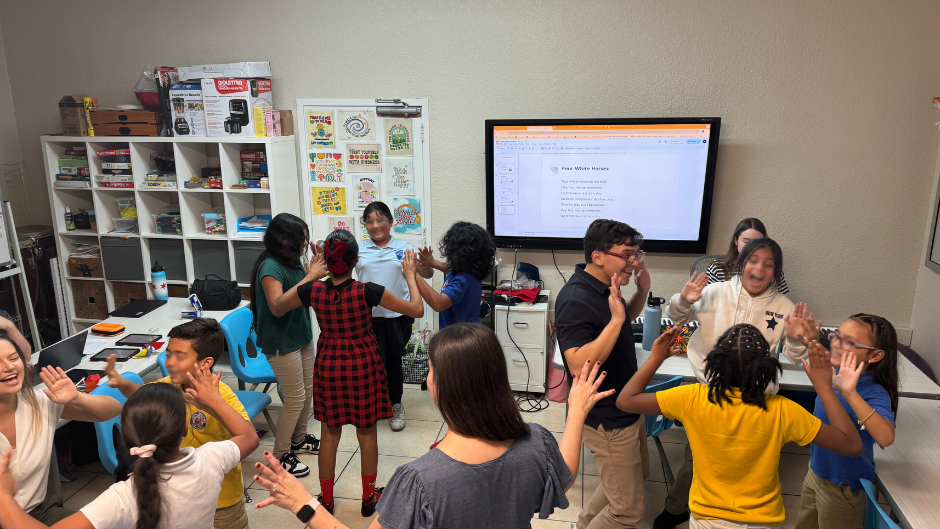

Abril invited two doctoral and three undergraduate students to run the complex project. Starting in early October, they met weekly with ten children, ages nine to 11, at the Little Havana center. They spent an hour with the children, alternating breathwork and relaxation exercises with teaching a number of songs, including Bruno Mars’s “You Can Count on Me,” “A Million Dreams” from the film The Greatest Showman, and “Matarile,” a traditional Latino children’s song.

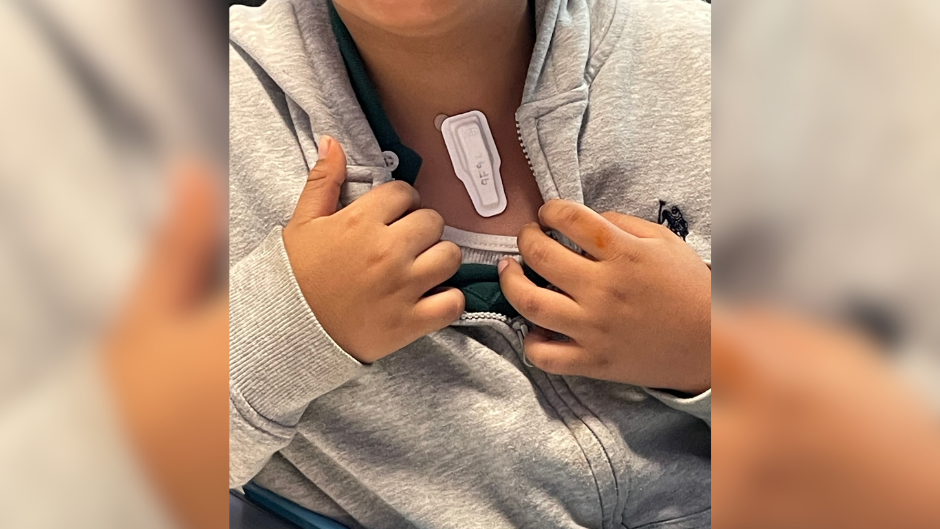

But it’s not a simple singing class. The Frost School students survey the children at the start and end of each session, asking the children to use emojis to show whether they feel calm, tense, upset, happy, and the like. Frost students also attach biometric sensors to the base of the children’s throats, which measure their breathing and heart rate. These sensors were designed at the Northwestern Medical School, especially for the project. The sessions are videotaped to compare biometric measurements with the children’s behavior.

Together, these assessments provide a complex, moment-to-moment picture of how singing and breathing affect children physically and psychologically. This spring, Abril and Birman will work with the Northwestern team to analyze the collected data, which will later be compiled and analyzed with information from other sites.

One of the sensors designed for the Music for Childhood Well-Being Initiative.

Photo by Dina Birman/courtesy Frost School of Music.

Kloss, who has taught private lessons and summer camps in her native Seattle, has gotten to know the children in Little Havana. There’s the boy who sings “You Can Count on Me” to her, a girl proud of her elaborate press-on nails and command of American slang, and a boy who yells delightedly when he knows a song. When they arrive in the late afternoon, tired after a long day, she sees how singing affects them, even for just an hour.

“I see them calm down with the breathwork, and with the songs their energy goes up,” she says. “At the end, they’re sitting up straighter, talking a lot more. They always walk away more lively. One of my kids always wants to race out of the room.”

The experience has changed how Kloss thinks about music. “I’ve seen music be performed, you teach it, you watch it,” she says. “I’ve never seen it done as a way to reach a conclusion on how it affects the child. This is a new way of using music.”