|

|

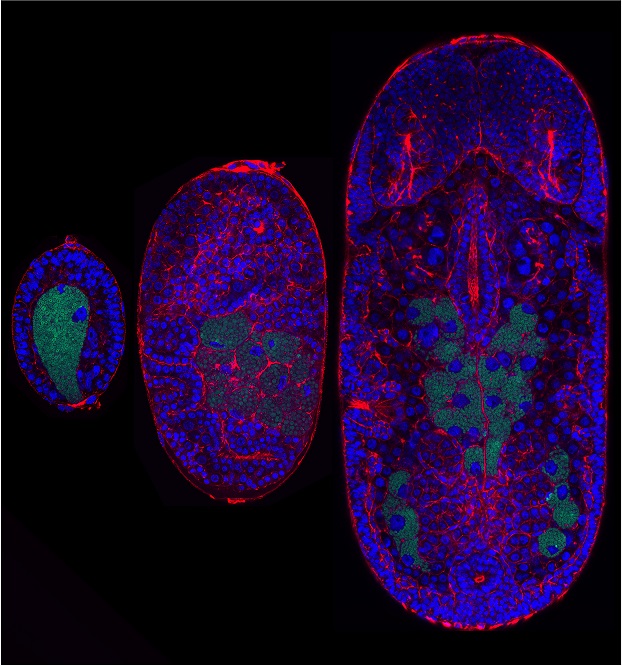

Buchnera symbionts supplement host aphids with essential nutrients absent from their diet. Pictured are pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, embryos at stage 7, 13 and 17. Aphid DNA is stained blue and symbiont DNA is pseudocolored green. By stage 17 symbionts are housed in aphid bacteriocyte cells forming a bacteriome. These confocal microscopy images were generated by in Alex Wilson’s laboratory at the University of Miami by Hsiao-Ling Lu from National Taiwan University with funding from National Science Foundation Award 1121847 and National Science Council of Taiwan NSC 102-2917-I-002-006. Photo credit: Thaddeus McRae, www.thaddeusmcrae.com |

Symbiosis is the process that occurs when two different organisms live together to form a mutually beneficial partnership. In many symbiotic relationships, host animals and their microbial symbionts are partners that make up a whole – neither one can function without the other but together they grow and reproduce.

A study by University of Miami (UM) researchers reveals how, at the cellular level, an animal and its symbiotic bacteria work together to make up a single organismal system. The study titled “Aphid amino acid transporter regulates glutamine supply to intracellular bacterial symbionts” is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS).

The findings show how a simple mechanism allows an insect, the pea aphid, to regulate the manufacturing of essential nutrients supplied by its symbiotic bacteria called Buchnera aphidicola.

“We’ve identified the key regulator of this symbiosis,” says Alex C. C. Wilson, associate professor of Biology in the UM College of Arts and Sciences and corresponding author of the study. “It’s our first real insight into the mechanisms working at the interface of the host and symbiont”

The pea aphid feeds on plant sap. Its diet is deficient in essential nutrients called amino acids. The aphid can produce some amino acids on its own, but the rest it must get from beneficial bacteria that live inside aphid cells. In turn, the symbiotic bacteria can’t produce amino acids that the aphid can make, so the partners exchange insect-produced amino acids for symbiont-produced amino acids.

“That conversion of going from a diet with an inappropriate nutritional profile, to an appropriate profile occurs in collaboration between the bacteria and the host,” Wilson says. “The question is whether the production of nutrients changes with supply and demand and if so, how it happens”

To help answer this question the researchers looked at amino acids that are fundamental to the pea aphid-Buchnera symbiotic function. One of those amino acids is glutamine, which is made in the aphid. Glutamine is important because it’s the precursor for all amino acids produced both by the aphid and by the symbiont. The other amino acid is arginine, which is made in Buchnera and it’s deficient in the pea aphid’s diet.

Glutamine is ferried across a membrane that surrounds the cells where the bacteria lives, by an amino acid transporter named ApGLNT1. To study this transport mechanism the researchers used a procedure that uses frog eggs (called oocytes) to manufacture ApGLNT1. This specialized approach is used by Charles W. Luetje, chairman of the department of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology in the UM School of Medicine and co-author of the study.

“My lab specializes in the use of a technique that allows functional studies of various receptors, channels and transporters,” says Luetje. “The oocytes are useful for expression of a wide variety of proteins and are particularly helpful when studying ‘difficult’ proteins that don’t express well in other systems.”

Based on their work figuring out what ApGLNT1 transports and where it is localized in the pea aphid, the researchers built a model that describes how the amino acid factory responds to supply and demand.

The findings show that when there is a buildup of arginine in the pea aphid, arginine binds to ApGLNT1, and inhibits glutamine uptake. Since glutamine is a precursor for amino acids, the bacteria’s synthesis of arginine is in turn reduced. Once arginine is assimilated by the host, glutamine transport resumes and synthesis of arginine is restored.

“To our surprise, the transporter is a key regulator of the factory production line,” says Daniel R. G. Price, who worked on the project when he was assistant scientist in the Department of Biology at UM and is first author of the study.

“When aphid demand for essential nutrients is high, the transporter imports large amounts of precursor and the precursor is converted into essential nutrients that are returned to the aphid,” Price says. “Conversely, when there is low aphid essential nutrient demand, little precursor is imported and the essential nutrient production factory is shut down.”

A remarkably basic mechanism regulates the biosynthesis of symbiont-produced arginine, in response to the needs of the pea aphid. But the model goes further than that.

“Since ApGLNT1 localizes to the membrane of aphid cells where the bacteria resides and because of other features peculiar to aphid metabolism, transporter ApGLNT1 not only regulates arginine biosynthesis, but all amino acid biosynthesis,” Wilson says. “The system is simple and elegant.”

Thus amino acid transporters play a key role in the evolutionary success of these insects. But an important question remains, how generalizable this regulatory mechanism is across symbiotic systems. Wilson’s lab may find the answer by looking at other sap-feeding insects with intracellular bacteria, based on an understanding that emerged from another study from her lab. The study titled “Dynamic recruitment of amino acid transporters to the insect-symbiont interface” is published in the journal of Molecular Ecology.

That study found that the presence of amino acid transporters is significantly expanded in some sap-feeding insects relative to non sap-feeding insects. Further, these expansions result from large-scale gene duplications that took place independently in different sap-eating insects. Gene duplication is a process that occurs when part of an organism’s genetic material is replicated. Groups of similar genes that share an evolutionary ancestry are called gene families.

“Given the extensive gene duplication of the amino acid transporter gene families that took place multiple times independently in sap-feeding insects, it makes sense that gene duplication might be important for recruiting amino acid transporters to mediate amino acid exchange between these insects and their symbionts,” says Rebecca P. Duncan, doctoral student in the Department of Biology at UM and first author of the study.

The sap-eating insects with expanded amino acid transporters come from a common ancestor. However, given that the genes expanded independently in each insect, sap-feeding insects likely evolved their relationships with their symbionts separately, as opposed to in their common ancestor. Hence, Wilson’s lab can test if their model is broadly applicable by examining the mechanism of symbiotic regulation in the other sap-feeding insects used in this study. The findings of these studies show that symbiotic relationships have the power to shape animal evolution at the genetic level.