Dr. Massimiliano Galeazzi, associate chair and professor of physics at the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, expressed profound excitement and eagerness when he spoke about his participation in the collaborative X-ray satellite mission with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and NASA earlier this year.

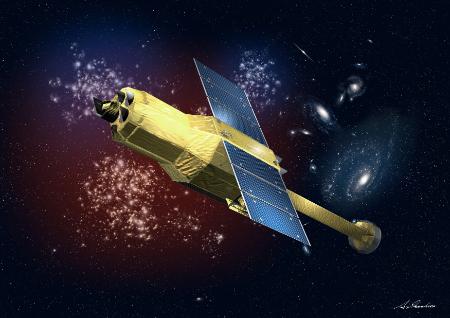

Known as the Hitomi mission, the satellite featured a next-generation X-ray instrument developed and built at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center by scientists from the U.S., Japan, and the Netherlands. As a member of the scientific collaborative team, Galeazzi was responsible for developing the systematic goals and strategies for the mission.

|

| A rendering of the Hitomi satellite. |

Designed to capture X-ray data from galaxy clusters and the warping of space and time around black holes, the Hitomi satellite, which translates to “pupil of the eye” in Japanese, suffered damage while in orbit less than one month after its launch in February 2016. A malfunction put Hitomi in an uncontrollable spin causing it to break up and lose its satellite function, a disappointing turn of events for Galeazzi and the team of the scientists.

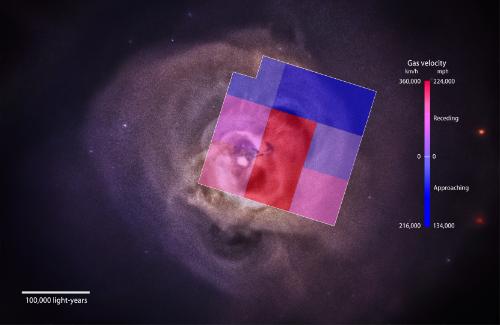

Before the satellite sputtered out, it successfully captured X-ray gasses emitting from the Perseus cluster of galaxies, a collection of galaxies joined by gravity and located 240 million light years from Earth. The cluster radiates hot gasses, averaging 90 million degrees, which before were unmeasurable by astrophysicists.

Scientists studied the data captured by Hitomi and found that the hot gasses between galaxies within the cluster are moving at a slower speed and in a less turbulent manner than expected – studying the movement and turbulence of gas is a vital tool for understanding the growth and parameters of the universe and how galaxies form and evolve.

“The level of details obtained by the investigation is breathtaking, showing the incredible power of the X-ray instrument aboard the Hitomi satellite,” said Galeazzi. “Although the satellite has been lost prematurely, the instrument has revolutionized the field of X-ray astrophysics and paved the way for the next generation of X-ray telescopes.”

The X-ray instrument abroad the Hitomi satellite measured an array of emissions from the cluster such as iron, nickel, chromium, and manganese – elements apparent in the stars located in the cluster’s galaxies. The satellite’s data also showed that the gasses’ turbulent motion is practically nonexistent, which leaves scientists to wonder what is keeping the cluster’s gasses so hot?

Professor Andrew Fabian at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, says, “This result from Hitomi is telling us that in terms of how cluster cores work, we have to think very carefully about what is going on.”

The X-ray data observed by Hitomi is an indication of the advances satellites can detect in the far reaches of space. The European Space Agency plans to send out a next-generation satellite in the 2020s, named ATHENA, the which will feature 100 times more pixels than Hitomi and be able to explore galaxy clusters and the relationship they play with massive black holes.

The findings from Hitomi’s data collection of the Perseus cluster was recently published in the journal Nature on July 7, and entitled “The quiescent intracluster medium in the core of the Perseus cluster.”

|

| Photo of Perseus cluster with gas velocity data captured by the Hitomi satellite. |

July 13, 2016