An interdisciplinary and international team of scientists and students set sail aboard the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) ship Ronald H. Brown on Tuesday, July 18 for a 36-day expedition in the Gulf of Mexico.

The researchers – including graduate student Joletta Silva and two recent alumni, Emma Pontes and Leah Chomiak, from the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science – represent institutions from the United States, Mexico and Cuba.

The expedition, entitled the Gulf of Mexico Ecosystems and Carbon Cruise (GOMECC), is the third of such research cruises led by NOAA AOML (Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory) for its Ocean Acidification Program to better understand how ocean chemistry along U.S. coasts is changing in response to ocean acidification. This cruise is the first that will explore Mexican waters of the Gulf of Mexico, and is considered to be the most comprehensive ocean acidification cruise to date in the region.

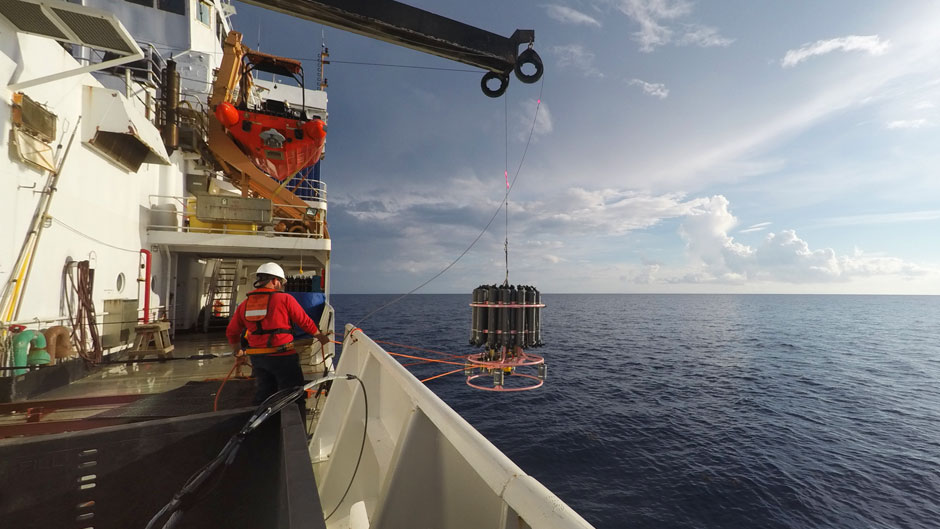

The journey began in Key West and includes 11 transects, or lines from the coast out towards the center of the Gulf, with a total of 107 sampling stations. A CTD (connectivity, temperature and depth) probe is a research instrument that will be used to deploy 24 bottles to collect water samples in surface, near-shore and deeper waters. Each sample will be analyzed for salinity, oxygen, nutrients, dissolved organic carbon, total alkalinity, pH level, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, dissolved organic matter, ocean color (to compare to satellite imaging) and microplankton community distributions.

Part of the cruise’s mission is to measure and analyze how ocean acidification is affecting marine life along the Gulf coast of the United States and Mexico, so samples of marine organisms—icthyoplankton (fish eggs and larvae) and pteropods—will also be collected during the research trip.

The more than two dozen researchers collaborating on this cruise are from the Rosenstiel School, NOAA AOML, CIMAS (Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies) at Rosenstiel, the National Park Service, the NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service, NOAA National Marine Sanctuaries, North Carolina State University, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, University of Southern Mississippi, and University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science in the United States; ECOSUR (El Colegio de la Frontera Sur), CICESE (Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada), Universidad Autonoma de Baja California in Mexico; and CEAC (Centro de Estudios Ambientales de Cienfuegos) and GEOCUBA in Cuba.

Follow the research expedition here through August 21.

August 11, 2017

Leah Chomiak, recent UM alum in marine science, chemistry and meteorology

Hurricanes & Hurricanes: The U at Sea

Last week marked the halfway point of our trip here in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico; some may say that time has flown by in a blink of an eye, while others say it has felt like years. Despite regimented sampling and endless analyses, spirits are high and each shift brings about a zest of excitement and new adventures. We are currently located in the Bay of Campeche, in the southern end of the Gulf, west of the Yucatán Peninsula. We are playing catch-up on a few transects that had an unexpected abandonment last week as we faced the arrival of Hurricane Franklin.

Prior to coming on the cruise, people asked me what I was looking forward to most about the GOMECC-3 endeavor. My answer (besides the groundbreaking science and ocean acidification work, of course) was to be in the Gulf in the heat of mid-hurricane season, with hopes we’d cross paths with a storm. Lo and behold, my wish came true and Tropical Storm Franklin came plowing down the pipeline earlier this week heading straight for our ship.

Ask anyone on board, and they will tell you that I was like a kid in a candy store with excitement for this storm. Who doesn’t like a little excitement in their life? The chief scientists and crew met many times to review options on how best to avoid the storm while also fulfilling the sampling mission of the trip. It was decided that we would cease southern transit and instead cut across the Gulf to the top of the Yucatan Peninsula, escaping the most probable path of Franklin.

The forecasts and trajectories proved true in the end (shout out to the National Hurricane Center and the National Weather Service—we appreciate you guys!). Because I am writing this now, I can assure that everything was fine and we survived the storm with no damage. We got to experience the outer bands of the storm as it continued to strengthen; winds were around 35 knots at their peak and, at one point, we observed waves 10-15 feet high.

Conditions were a little sporty, as I’d call them. But, man, was it awesome clinging to the bow and riding those waves! The storm made landfall in central Mexico, and now we are finally in the clear and back in motion. The ship made a 180-degree turn at the tip of the Yucatan, heading back to the Southern Gulf to return to our originally planned transect lines. From an oceanographic perspective, it was awesome to see our sampling results from where the hurricane conditions had affected the water column structure. Surface temperatures were cooler, the mixed layer was deeper, and water was more turbid—cloudy and unclear—all results of a hefty storm passing through.

We are now closing in on our last few days of the cruise, and the Ron Brown will slowly start making its way back to our end port of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, clocking in a few more stations before then. As of today, Emma [Pontes] and I have analyzed just under 1,000 oxygen samples—kind of crazy to believe, but super exciting to have all of this great new data! With stormy seas in our wake and clear skies ahead, we push onward, toward whatever adventures await us in these final days!

July 22, 2017

Emma Pontes, recent Rosenstiel M.P.S alum in marine biology and ecology, currently working as a research assistant for Rosenstiel’s Department of Marine Biology and Ecology

Breathing in Science: Oxygen Measurements at Sea

Take a deep breath. The air you just inhaled contains about 20 percent oxygen, 78 percent nitrogen, and 2 percent other minor gases. Some might assume that oxygen is only available to terrestrial air-breathers, but this couldn’t be further from the truth.

There is a constant ebb and flow of carbon dioxide and oxygen being ‘inhaled’ and released into ocean waters. Oxygen (O2) generally exists in a gaseous state, but it also exists in the world’s oceans as a dissolved gas. Fish and other ocean biology use the dissolved oxygen just like humans do—taking up O2 and releasing carbon dioxide (CO2). Millions of organisms that call the ocean home, such as plankton, algae, and other underwater plants, take up CO2 and release O2 during a process called photosynthesis.

What does this mean for ocean chemistry, and why do we care? Dissolved oxygen in the ocean is a sensitive indicator of climate-related changes. And, just like oxygen, CO2 can dissolve in ocean waters. The dissolved oxygen concentration can be used to determine how much anthropogenic CO2 (carbon dioxide released by humans resulting from the burning of fossil fuels) is being taken up by the ocean.

Most of human-created CO2 has been sequestered by our oceans and this uptake is a leading cause of ocean acidification. Determining the O2 concentration at different locations in the world’s oceans is thus very important for learning more about the effects of ocean acidification and how ocean biology is functioning under these conditions.

Enter GOMECC-3, Ocean Acidification Research Cruise. In the past, research vessels have traveled our current route collecting the same data we are gathering now at the same locations. Comparing data we collect from this cruise to the historic data sets collected by past research cruises on this same path, we can get an idea of how ocean chemistry is changing over time.

Research on the ship helps us also learn how ocean chemistry changes with depth. Work days on the ship consist of lowering the CTD (conductivity, temperature, and depth) rosette—a large cylindrical ring of bottles—into the ocean at a set locations called Stations. Each bottle in the CTD is called a Niskin, and each is triggered to collect water samples by shutting its lid at predetermined depths.

My job on the ship is to collect water samples from the Niskin bottles and analyze each sample for its dissolved oxygen concentration using a technique called Winkler Titration. This procedure requires adding chemicals that act as a fixative to the water sample; the chemicals bind to the oxygen in the water and create a solid precipitate that eventually sinks to the bottom of the water sample.

It can be thought of as ‘pickling’ the oxygen to preserve it, so that the sample can be studied anytime from one hour to four weeks after being collected. To learn more about the titration procedure, check out the peer-reviewed paper entitled ‘Determination of Dissolved Oxygen in Seawater by Winkler Titration Using the Amperometric Technique’ written in 2010 by Chris Langdon, professor and chair of marine biology and ecology at Rosenstiel. This paper basically serves as my lab manual on the ship. I am looking forward to collecting some meaningful data that will contribute to ocean acidification research as we continue our trip around the Gulf of Mexico!

July 21, 2017

Joletta Silva, M.P.S student in the Rosenstiel School studying marine conservation

I arrived to the ship on Monday, July 17, and it was even bigger than I had anticipated. I’ve participated on research cruises, but none for longer than 3 weeks. This is also my first time analyzing carbon, so it is definitely a new experience for me.

I am a graduate student at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science getting my Master’s degree in Marine Conservation. I am currently on a 36-day cruise—the third GOMECC cruise— going around the entirety of the Gulf of Mexico and working as a dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) tech, employed by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). GOMECC stands for Gulf of Mexico Ecosystems and Carbon Cycle, and the purpose of the GOMECC cruises are to analyze the parameters of ocean acidification, a huge issue in coastal waters that can impact countless species and ecosystems. Ocean acidification is also a key component of global warming, and gathering more details about its impact as well as monitoring changes over time is crucial to understanding this phenomenon.

I have already met most people on the ship and they are extremely nice and helpful. We have about 30 scientists from 5 different countries and about 25 crewmembers. The ship set sail from Key West. The first day I began the walk from my hotel to the ship, carrying my bags and sweating from the heat, but thankfully I ran into the chief scientist Leticia Barbero and we rode together to the ship’s port.

After boarding the ship, I finally found my room after getting lost through the countless passageways and hidden stairwells. It was quite an experience. I’m sure in a few weeks this ship will be as familiar as the back of my hand, but for the time being, I have no idea where I’m going. All the hallways and doors look the same. The room is nice, with bunk beds and a lot of storage space. I was given a quick tour of the ship and I have to say that my favorite place on deck, by far, is the bow. It is huge and the view is awesome.

After this I went to work with Patrick Mears, a research associate from the CIMAS (Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies) program at UM, which coordinates its efforts through the NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML). We’re both studying DIC on the cruise. We work in a lab that is separate from the main lab and is in a large shipping container. This is advantageous since we don’t have to worry about a very complicated setup, and we are pretty isolated so we can listen to music or stroll outside. That being said, as we’re so secluded, I plan on periodically walking over to the main lab to talk to the other scientists. I’ll be working the night shift—11:30 pm to 11:30 am—so I have some adjusting to do in terms of my sleep schedule.

A few hours after boarding the ship, we pushed off the dock and the adventure began! I am so excited to be part of this journey and I know that the experiences I will have, the skills I will learn, and the people I will meet will be invaluable. I can’t wait to get started.

Check back next week for updates from the UM Rosenstiel team, and follow along with the whole crew’s voyage here.

GOMECC-3 Cruise Blog Week of July 17

July 20, 2017

Leah Chomiak, recent UM alum in marine science, chemistry and meteorology

It’s day 2 here on the Ron Brown, and all souls on board have been busy adjusting to new sleep schedules, new office views and a constant influx of incoming samples. Our first day out was nonetheless perfect—flat glassy seas, clear skies, and a slight breeze, with sightings of whales, dolphins and tuna schools in the distance. As this is my first time sailing on the Brown, I’ve spent most, if not all my time, wandering around the ship, taking in the ocean vistas, getting to know the crew and fellow scientists and figuring out the endless maze that is the Ronald H. Brown.

I can definitely say that the engine room is a great place for hide and seek; maybe we can get that game going later on in the transit! With our melting pot of individuals onboard, it’s been really fun to get to know everyone and hear how they ended up working on the Brown. Our crew diversity spans individuals of Navy, Army, Merchant Marine, Coast Guard, and NOAA Corps backgrounds, each with awesome stories of time spent at sea and working with NOAA. Our scientists hail from all over the western hemisphere, with undergraduates, graduate students, senior scientists, and technicians each bringing their own zest, humor and wealth of knowledge to the mission.

Life on board has been pretty great so far! Mealtime is a conglomeration of most bodies onboard, where the engineers and other crew crawl out of their caves, bunks, hatches, labs and the bridge to feast. You’re guaranteed to see someone you’ve never seen before each time you eat. There is a library and movie room onboard, both with hundreds of selections of titles that are sure to please anyone. My favorite spot on the ship is definitely the bow, perfect for staring down at that “no-land-in-sight” ocean blue color, my favorite color that one cannot describe unless they’ve been out to sea. Working the night shift (midnight to noon), I am fortunate to work through a sky filled with billions of stars, and watch the sunrise each morning. Ah, rough life, right? Someone’s gotta do it!

Our first station came at 2000 (8:00PM) off the coast of Dry Tortugas National Park, and the entire science crew crowded the deck to watch our massive, pink-framed, 24-niskin bottle CTD rosette be lowered for our first crack at sampling. It was a frenzy as soon as it was back onboard. Sampling teams crowded the rosette with their empty bottles, ready to be filled with water samples from the surface, mid-depth, and bottom. After a successful collection, teams returned back to their labs to process the samples sequentially, and prepared for the next station. In addition to CTD cast stations, underway sampling is collected every 3 hours from a spigot within the lab that is constantly pumping seawater from the surface. Sampling teams collect these samples to observe changes in the surface parameters during our sampling track, such as looking at changes in temperature, salinity, oxygen, pH and nutrient parameters.

We are currently in a 24-hour-plus transit until station 2 is reached, therefore things are a little quiet on board—the calm before the storm (of samples), I should say. Once the first transect is reached, we will be coming up on back-to-back stations and all scientists will be working throughout the day and night to ensure all samples get processed in a timely fashion. I am so thrilled to be on board, it’s been a blast already! Let’s science!

Cheers!