When U.S. Attorney Wifredo “Willy” Ferrer walked into the kindergarten class at Dunbar Elementary one recent Tuesday, many of the 18 youngsters shrieked with delight and swarmed him in a group hug. One boy even raced around the classroom, shouting in glee.

It was the kind of welcome usually reserved for a Disney character or superhero, but on this morning and at this school in Miami’s violence-plagued Overtown neighborhood, neither Spiderman nor Elsa the Snow Queen could compete with South Florida’s top law enforcement official. After all, Ferrer, a Miami native and University of Miami alumnus, returned to Dunbar to sprinkle his special blend of pixie dust—the kind that infuses youngsters, some who had never seen a book at home, with the love of reading.

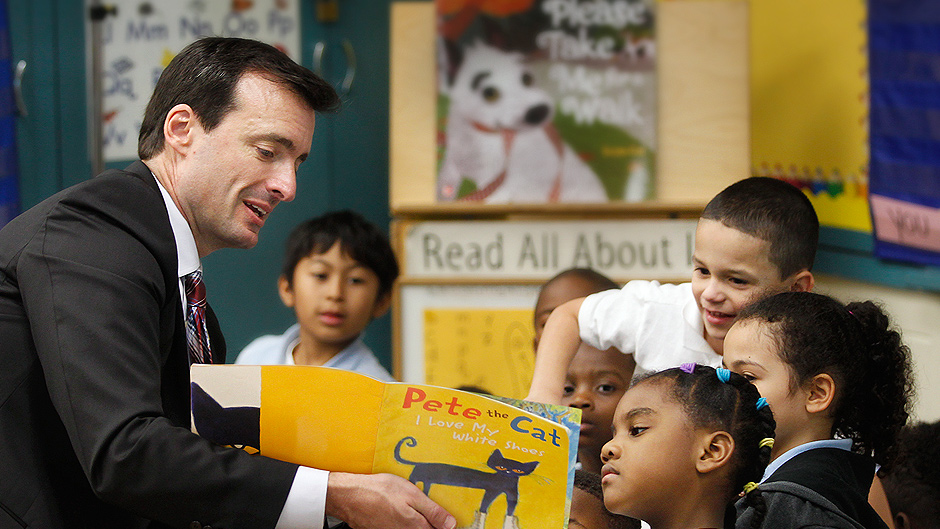

For the next hour, Ferrer, Keisha Bazile, a community resource specialist in his office, and Johanna Rousseaux, an attorney from the Miami office of the Jones Day law firm, would take turns reading Pete the Cat’s I Love My White Shoes, Dora’s Shape Adventure, and other books that weave basic learning and valuable life lessons into engaging stories the 5-year-olds in teacher Maria Fernandez’s class already knew by heart.

Down the hall, other staffers from the U.S. Attorney’s Office were taking turns reading in two others classes, where the children were equally excited by their monthly visitors—for they knew the best was yet to come. They knew their guests would not leave without giving each of them another book for their home library. Over the past two years, volunteer readers in the U.S. Attorney’s Monthly Pre-K Reading Program have handed out more than 11,000 books in 20 “hotspot” preschools and elementary schools in four counties.

“Which is probably why they come up and hug me,” said Ferrer, who always has embraced UM’s mission for community service. “Because they know they are going to get a book, but how great is that? Kids jumping up and down when you give them a book—that’s exactly what we want.”

Taking what he calls “a more holistic approach to fighting crime,” Ferrer launched the reading program as part of a three-pronged Violence Reduction Partnership in 2011, about a year after President Obama tapped him to lead the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida. Spanning nine counties and serving six million people, the Southern District is the third largest and one of the busiest in the nation, which would seem to leave little time for prosecutors, support staff, and volunteers from other law enforcement agencies and law firms to read to 900 3-, 4- and 5-year-olds every month.

But soon after taking office, Ferrer decided his staff shouldn’t focus solely on enforcing federal laws and holding those who break them accountable, which is the first priority and first prong of his Violence Reduction Partnership (VRP).

“That is our primary role,” he said. “But we are public servants and there’s no reason why we can’t be problem-solvers, too. There’s no reason why we can’t take a broader look at our role. We are here to keep the community safe, so we should try to do whatever we can to break that cycle of violence that plagues many of our communities.”

The son of Cuban refugees who graduated first in his class at Hialeah-Miami Lakes High School in 1984 and at UM’s College of Arts and Sciences, where he studied economics, in 1987, Ferrer looked at his own childhood and cold statistics for solutions to preventing crime—the second prong of his VRP strategy. Instilling preschoolers with an excitement for reading soon emerged at the top of the list.

“My parents left Cuba with one suitcase. I grew up in Hialeah with nothing, but my parents read to me every night,’’ he said. “They always told me, ‘We can’t give you an inheritance, but we can give you an education,’” Ferrer recalled. “That had a big impact on me. But in the ‘hotspot’ communities we identified—those with the highest levels of violence—there are too many kids who aren’t proficient readers, too many kids who don’t raise their hands when you ask how many have books at home.”

He knows the studies and prison statistics by heart: Children who don’t learn to read proficiently by the third or fourth grade are four times more likely to drop out of school, and more likely to land in prison.

“If you can’t read, you don’t perform in school, you don’t graduate, you can’t get a job. It’s a cycle you see in our state and federal prisons,” Ferrer said. “More than half of prison inmates can’t read proficiently so the one issue we decided to tackle, because we can do only so much, was literacy.’’

For now, Ferrer only has anecdotal evidence to show that the pre-K reading program, which was originally funded by a U.S. Department of Justice grant but now relies on donations, is making a difference. He points to one group of children who, after a year of readings by visitors who became role models, posted the highest reading scores for their age in their school.

“There’s nothing that means more to me,” Ferrer said. “As they say, reading is the foundation of learning, and if we can instill a love of reading early, I know it will pay dividends down the road.”

But in hotspot communities, the road often leads to prison, which Ferrer visits almost as regularly as the schools. As part of the third VRP prong, re-entry, he and an array of service-providers meet with soon-to-be-released prisoners to ask what they need to make the transition to freedom, and to remain there.

“I tell the inmates, ‘I know it sounds strange coming from me, since my office put you here, but we want you to be successful. We want you to have a great start when you leave so you don’t come back.”’

Ferrer knows, though, that the best start is the kind preschoolers get when someone hands them a book and they jump up and down with glee.

For more information about or to volunteer with the Violence Reduction Partnership's Pre-K Reading Program, please contact Law Enforcement Community Coordinator J.D. Smith at 305-961-9134 or usafls.vrp@usdoj.gov.