The somber roll call started precisely at 10 a.m., just as the morning sun dried the last few patches of moisture from a previous day’s rain.

Yosil Hollender, 6.

Sany Leb, 3.

Cesia Norman, 4.

Liebele Burstein, 1.

Those were among the youngest victims of the Holocaust, children who were killed in death camps like Auschwitz and Treblinka, some shot as they lined up at the edge of open pits, others led into gas chambers.

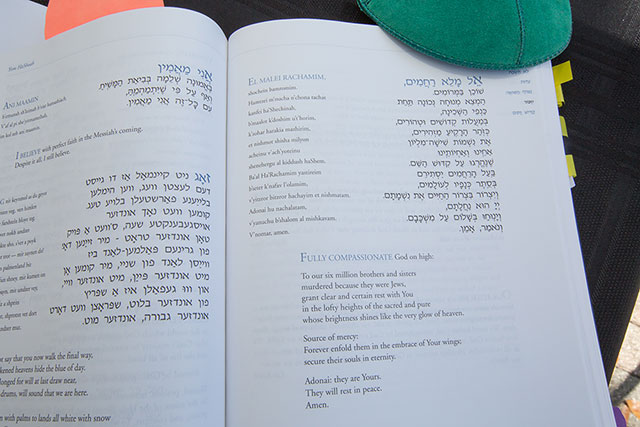

As the world commemorated Holocaust Remembrance Day on Monday, the University of Miami marked the occasion with a reading of the names of children who were murdered during a horrific genocide that claimed the lives of six million European Jews.

“When you hear ages like 3, 5, and 1, that’s powerful. You feel it. These were lives cut short,” said Lyle Rothman, campus rabbi and Jewish chaplain at UM Hillel, who organized the reading, held on UM’s Rock Plaza.

Rothman obtained the list of names from Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. The reading lasted six hours, but that wasn’t nearly enough time to cover every name on the list. Volunteers—students, faculty, staff, and community residents—read the names and the ages of each victim.

Sophomore Harrison Kudwitt volunteered because he feels it is important to keep the memory of Holocaust victims—and survivors—alive. “Soon, there’ll be no more survivors left,” said Kudwitt, who recently traveled to Israel for the first time. “The number of Holocaust deniers grows every day. To come out here to read the names of the children who died in this genocide is a reminder, a wakeup call that this is something that happened only 70 years ago.”

Shay Strelzik fought back tears when she read the age, 12 months, of one of the youngest victims on the list. “There were no words to describe how I felt,” she said.

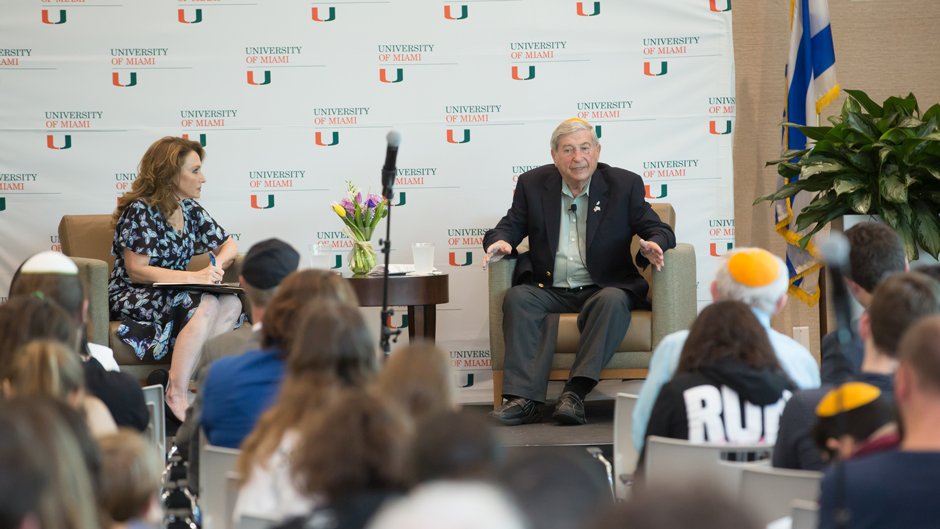

Some survived the Holocaust. Like David Mermelstein, who was only 15 when he and his family were loaded onto boxcars in Hungary in 1944 and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. When the train arrived at the camp, “they lined us up five in a row. There was a wire fence. We saw old men and women walking with canes, children playing with dolls, boys playing with balls, and men in striped clothes playing Jewish music,” recalled Mermelstein, speaking at the event, Conversation with a Survivor, held at UM’s Braman Miller Center after the reading.

|

| Names of victims of the Holocaust were read aloud during a six-hour event at UM’s Rock Plaza. |

At Auschwitz-Birkenau, those considered able to work were taken into the camp, while those deemed unfit for labor were immediately killed in the gas chambers. Josef Mengele, the notorious SS officer and physician who selected victims to be put to death and performed deadly human experiments on prisoners, separated Mermelstein from his grandparents, parents, and younger sister, sending them to the gas chamber. Mermelstein was able to avoid the same fate by stepping onto the shoes of his two older brothers to make himself look taller and older so that he could work in the camp.

He and a group of other prisoners were taken to a barracks and given striped uniforms. When they asked when they could see their parents and sisters, a guard motioned them to the door and opened it, saying, “Do you see the chimney? Do you see the smoke? There are no parents and no brothers and sisters.”

Mermelstein was later taken to another concentration camp that was eventually liberated by the Red Army. He weighed only 40 pounds on the day of his liberation.

When asked by the event’s moderator, UM first lady Dr. Felicia Knaul, professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the Miller School of Medicine and director of the University of Miami Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas whose father was a Holocaust survivor, how he persevered, Mermelstein said it was only through the urging of his older brothers “to never give up.”

Today, Mermelstein lives in Miami and is vice president of the Holocaust Survivors Foundation USA. “We don’t want the world to ever forget,” he said.

During the event, Knaul related the story of her father, Sigmund Knaul, who spent five years in Nazi concentration camps and lost almost his entire family in the Holocaust. He was accepted into Canada on a scholarship for Auschwitz survivors.

“For almost 40 years he made a life and a home in the best way he could in Toronto,” she said. “He died at the age of 60 of a cancer that was severely complicated by the scars of his internment and his starvation and exposure to disease.”

Knaul was only 18 when he passed. “He would have been 93 today,” she said. “My earliest memories of my own childhood are of overhearing him read his poetry. I must have been only 4.”

She and her daughter Hannah honored him by reading one of his poems.

Said UM President Julio Frenk, whose grandparents fled Nazi Germany, “The Holocaust has shaped not only the lives of those directly affected by the atrocities, but actually the lives of every single person on this planet because it showed the extremes to which the corruption of our fundamental social fabric—the values of tolerance, inclusion, and respect for human life—can take us. And this is why it is so important that we never the depths to which humans can fall.”