Only one member of the Peña family of “¿Qué Pasa, USA?” fame was at the Newman Alumni Center on the evening of January 31. But all the characters who starred in America’s first bilingual sitcom were there in spirit.

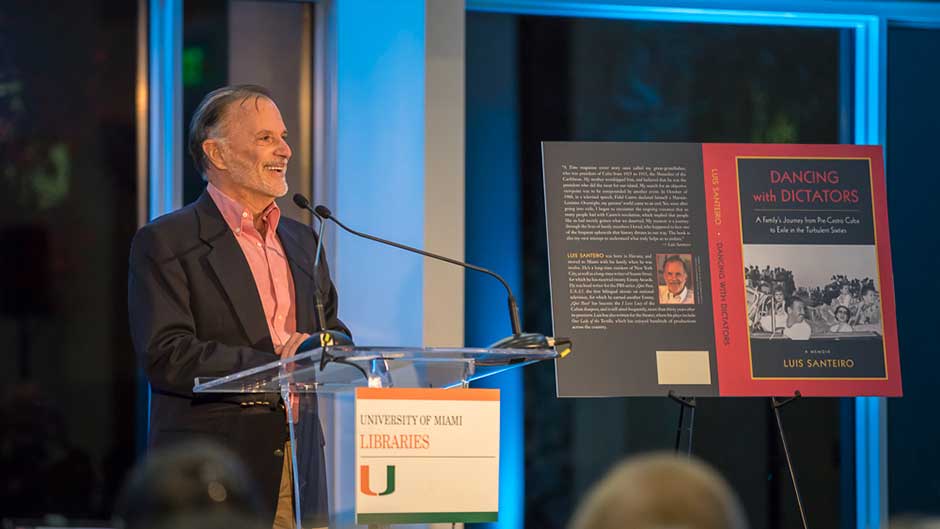

Luis Santeiro, the award-winning screenwriter of the popular PBS series, was warmly greeted by a very enthusiastic audience of nearly 200 fans, most of them Cuban-Americans, who have fond memories of the popular show.

Hosted by UM Libraries and its Cuban Heritage Collection (CHC), the star of the evening was Santiero’s memoir, “Dancing with Dictators: A Family’s Journey from Pre-Castro Cuba to Exile in the Turbulent Sixties,” from which he read.

Dean of Libraries Charles Eckman welcomed the audience and gave an overview of the CHC’s role in “preserving and providing access to the cultural heritage of Cuba by collecting books, photographs, letters and other records.” Santeiro himself donated all his documents, including the original scripts for the bilingual sitcom, to the CHC in 2003.

Others who spoke were Aida Levitan, chair of the Amigos of the CHC, and Luis Santeiro's brother, Frank, also a member of the Amigos board, who introduced his brother. Manolo Villaverde, the actor who played Pepe Peña, the sitcom's stubborn Cuban dad who called his children “Sonny boy'' and “Sonny girl,” was in the audience, but did not speak.

Born in Havana, Cuba, Santeiro left his native country at age 12, when his family escaped the Castro regime. The memoir spans the period from the mid ’50s to the ’60s.

Although his great-grandfather was Gerardo Machado, president of Cuba from 1925-1933, Santeiro told the audience that he deliberately avoided politics in his memoir. Instead, he chose to share the memories of his family members in their own voices.

“When I started writing it as a memoir I found that I loved it,” he said, noting he initially tried writing the work as fiction. “All these memories started coming back to me and I was spending time with people that I loved who were no longer here.”

He read a moving excerpt about the day in October 1960 when Fidel Castro, after “hemming and hawing” about his political tendencies, declared himself a Marxist-Leninist and read a list of the companies on national television that he was nationalizing.

Santeiro’s parents were home—sick with the Asian flu—and watched the telecast. After it ended, all the businesses the Santeiros owned were seized. The next morning, when his father showed up at Crusellas and Company, which had belonged to his family for generations, he was stopped by a “miliciano” or revolutionary police member. Santeiro read in his father’s voice:

“There was a young miliciano posted at the main gate who told me that this was no longer my property and I would not be allowed in,” he read. “But I sped on past him, quickly parked and headed to my office.”

His father, Santeiro said, ran into two other men who tried to stop him as he entered his office. One of them was one of his “loyal” employees.

“You have to leave the building,” he was told. “The company now belongs to the people.” When the senior Santiero protested, saying that his family name was still outside, one of the men curtly responded, “That will soon be gone.”

As Santeiro’s father gathered his belongings to leave his office, he stuffed several picture frames into a box and noticed one with a poignant engraving: “To our beloved Luisito from your ever grateful staff – Christmas 1958.”

Although the exile experience related in Santiero memoir is painful, there is humor throughout his narrative. He recalls the never-ending tide of newly arrived Cuban refugees who would set up “pin-pan-puns,” or makeshift cots, in the Santeiros’ modest Miami apartment, as well as his grandmother’s friends who reminisced about their days on the island.

One lady asks another: “What do you miss the most about Cuba?” he read. “I must say that what I miss the most is my bidet. Had I known that they were not available here I would have brought one instead of my husband.”