His abdomen distended and tender, the 6-year-old boy had gone without medical attention for four days. A ceiling had collapsed on top of him in the mayhem of Haiti’s devastating 7.1-magnitude earthquake, crushing his pelvis. Now, the boy lay in a makeshift infirmary at the U.S. Embassy in Port-au-Prince, which was being used by doctors to treat quake victims.

Henri Ronald Ford, a Haitian-born pediatric surgeon who flew to his homeland from Los Angeles to care for the injured, knew that if the youngster didn’t get immediate care, he would surely perish. “But there was no place to operate on him at the embassy,” Ford recalls. “We used a closet as a surgical suite to perform amputations. But this boy required much more serious surgery with intubation.”

So Ford and the boy were airlifted by helicopter to the USS Carl Vinson, anchored off the coast of Port-au-Prince to support disaster relief efforts. There, in the supercarrier’s better-equipped medical facility, Ford saved the boy’s life, staying aboard ship to treat other victims—among them, a girl with a piece of concrete embedded in her skull.

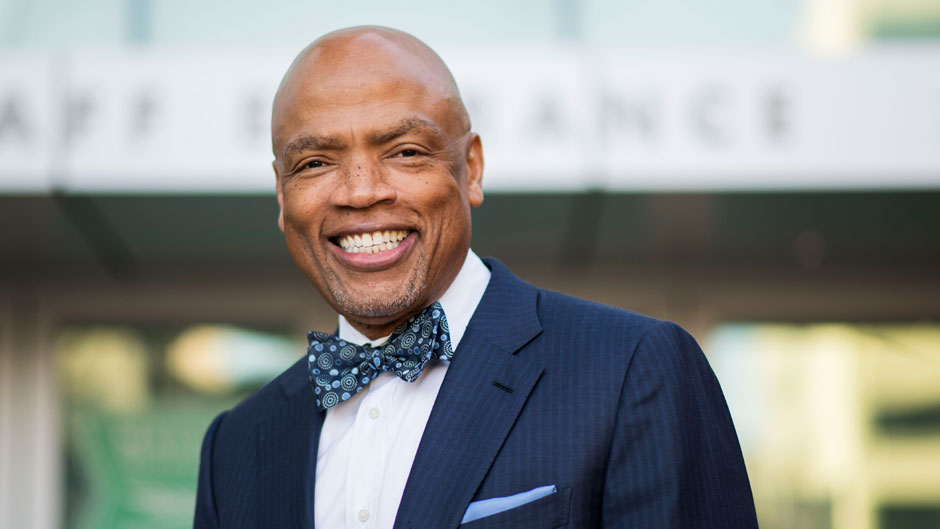

Ford’s devotion to his discipline and desire to help others doesn’t surprise those who know him well. Indeed, the surgeon “always has the best interests of children at the forefront of everything he does,” Richard D. Cordova, the former president and CEO of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where Ford serves as vice president and chief of surgery, once said.

Now, Ford—who in 1972 at the age of 13 fled with his family from the government of Papa Doc Duvalier, settling among the Haitian community in Brooklyn, New York, and going on to earn a bachelor’s degree from Princeton and an M.D. from Harvard Medical School—is poised to begin the latest chapter in a life that embodies the American Dream.

On June 1, he joins the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine as its new dean.

Ford, the son of a preacher, calls it his “dream job.”

“As I reflect on my journey in American medicine, I feel that I’ve been preparing all my life to assume what is an incredibly important role for such a time as this,” said Ford, who is also professor and vice chair for clinical affairs in the Department of Surgery at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine. “As a physician-scientist, physician-educator, and administrator, I feel that I must establish a culture of excellence in scientific research and promote the translation of discoveries into interventions that will transform lives, build healthier communities, and improve global health.”

Ford had been considered for deanships at other medical schools in the past, but had always turned them down, hoping that the UM job would one day open up.

“I’ve always said that the only reason I would consider leaving my current position is to become dean of the Miller School of Medicine,” said Ford, explaining that University of Miami President Julio Frenk’s vision of making UM the hemispheric, excellent, relevant, and exemplary university is why the Miller School job appealed to him.

“The Miller School of Medicine has a unique opportunity to leverage the strength of UHealth, its affiliated hospitals, and other schools and colleges, as well as its outstanding centers and institutes, to achieve this goal and strengthen its national and international preeminence,” Ford said.

UHealth and the Miller School, he said, must become “the preferred destination for people seeking the latest advances in healthcare and biomedical research, especially since we are the gateway to Latin America and the Caribbean. We must become an incubator and a major hub for both clinical and biomedical innovation and partner with our executive vice president and CEO of UHealth, Dr. Edward Abraham, and our provost, Jeffrey Duerk, to help UHealth and the Miller School of Medicine achieve their fullest potential.”

Lofty and ambitious goals are nothing new to Ford. He graduated from John Jay High School in Brooklyn despite speaking no English when he came to the United States.

“The principles that my father and mother had inculcated in our minds pretty much were applicable whether in Haiti or in the United States,” said Ford, the sixth oldest of nine children. “We had to work hard and do our best. There was no satisfactory substitute for excellence. So I had to quickly learn English so I could adapt.”

And adapt he did.

As an undergraduate at Princeton, he augmented his premed courses with classes in politics, international affairs, and philosophy. “I felt challenged at all times, and I had the freedom to explore different opportunities because there was a potpourri of outstanding disciplines that were readily accessible to me,” Ford said. “It was a smorgasbord of all sorts of great things, like being at a high-end buffet and not knowing how to fill your plate.”

At Harvard Medical School, he quickly realized that he could make the biggest impact as a physician by becoming a pediatric surgeon.

“An excellent general surgeon can have a great impact on someone’s life because he or she has to be an internist who possesses the technical skills to operate, bringing immediate relief to human suffering when it comes to certain conditions,” Ford explained. “Let’s say you have an 85-year-old who presents with bowel obstruction from cancer. If I operate on such a person, I can add potentially another 5 years to that person’s life expectancy.

“However, when you operate on a newborn with a surgical emergency, you know that if you don’t intervene, that child is going to die,” Ford continued. “And because of your intervention, you are adding potentially 85 to 90 years to that child’s life expectancy. That is truly priceless. So for someone whose overarching desire in life has always been to make the greatest difference possible in the lives of others, there was just no question as to which discipline I needed to pursue.”

While completing a fellowship in pediatric surgery at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Medicine, Ford became troubled by a disease—necrotizing enterocolitis—that often kills premature babies, despite aggressive medical and surgical intervention. So he decided to devote his career to understanding how and why babies developed the disorder in which tissue in the small or large intestine of preemies is injured or begins to die off.

His research group became the first to demonstrate how microbes in the intestine and nitric oxide lead to the pathogenesis of the disease. “We believe our discoveries will lead to new interventions,” Ford said.

In 2015, Ford performed the rarest and riskiest operation there is: the separation of conjoined twins. In the first operation of its kind in Haiti, Ford led a team of surgeons in separating 6-month-old infants Marian and Michelle Bernard.

But long before that, Ford had been performing life-saving operations on children. When the massive earthquake struck Haiti on January 12, 2010, resulting in massive loss of lives, Ford and his two brothers, who are also physicians, traveled to their homeland to help. “We knew this was the kind of catastrophe where we couldn’t just send money,” Ford said. “We had skills that could impact the survival of people, and it was important that we used the skills we had acquired to intervene at such a time. In my case, as a pediatric surgeon with expertise in trauma and critical care, there was no way I could justify just staying in Los Angeles at a time after bricks and concrete had fallen on little kids. We knew access to physicians was limited and that people with surgical emergencies were not being treated. For me, it was just how quickly could I get there. I called my brothers, and they said they would follow me.”

Port-au-Prince after the quake was nothing like the city of his youth. The temblor flattened his father’s church and the elementary school he attended. Eighty percent of the roads were impassable, and decomposing bodies could be found under much of the rubble.

“It’s simply difficult to explain the magnitude of the human suffering, the devastation I witnessed,” Ford said. “No television reporter could transmit it as effectively as if you were there watching it and experiencing it, and that’s why I knew after my two-week engagement there—the most grueling two weeks of my life—that I couldn’t say I was done. I knew that this was going to require continued investment in trying to build an infrastructure to deliver trauma critical care, for had one existed, the morbidity and mortality that we encountered would have been far less.”

So Ford has made several trips to Haiti since the earthquake, working with the Ministry of Health to reform medical education and build an infrastructure to support teaching. But it hasn’t been easy, as a lack of resources has challenged Haiti’s ability to build the right classrooms and laboratories and equip hospitals and clinics “so they can actually provide the care necessary to patients and make sure students have the opportunity to participate in critical care,” Ford said.

What he’s accomplished is to teach medical students and teach residents and attending surgeons in Haiti how to recognize and manage neonatal surgical emergencies. “I’ve tried to make sure we focus on transferring skills to Haitian healthcare professionals because it’s important that not only they recognize problems and manage them, but also ensure that post-operatively they can provide the level of care that is going to be necessary for newborn infants to survive,” Ford said.

He is looking forward to becoming dean of a medical school that has a long history of providing care in Haiti. In conjunction with Project Medishare, the Miller School and the School of Nursing and Health Studies have brought critical and primary care, medical equipment, and training to Haiti.

“I’m very excited about the tremendous opportunity to potentially help Haiti establish a much-needed trauma and critical-care infrastructure so that Haitians don’t have to jump on an airplane to come to the U or Jackson Memorial for treatment or simply die in country whenever they sustain significant multisystem trauma, a heart attack, or a critical burn,” he said. “And the same also applies to other impoverished Caribbean and Latin American nations that may potentially benefit from the expertise that is readily available at the Hemispheric University.”

Ford has a history of his own with UM. Nearly 17 years ago, his sister, Marlene, the principal of the American Union School in Port-au-Prince, suffered burns over 35 percent of her body when her dress caught fire. Haiti didn’t have a burn center, so the family airlifted her to the UM/Jackson Memorial Burn Center, where she spent six weeks in the intensive care unit.

“She was on the brink of death, and we really didn’t think she was going to make it,” Ford said. “But thanks to the miraculous work of the great doctors from the U and Jackson, they were able to save her. She underwent multiple grafting operations, but today she is fully functional. We owe her life to the doctors at the U and Jackson.”