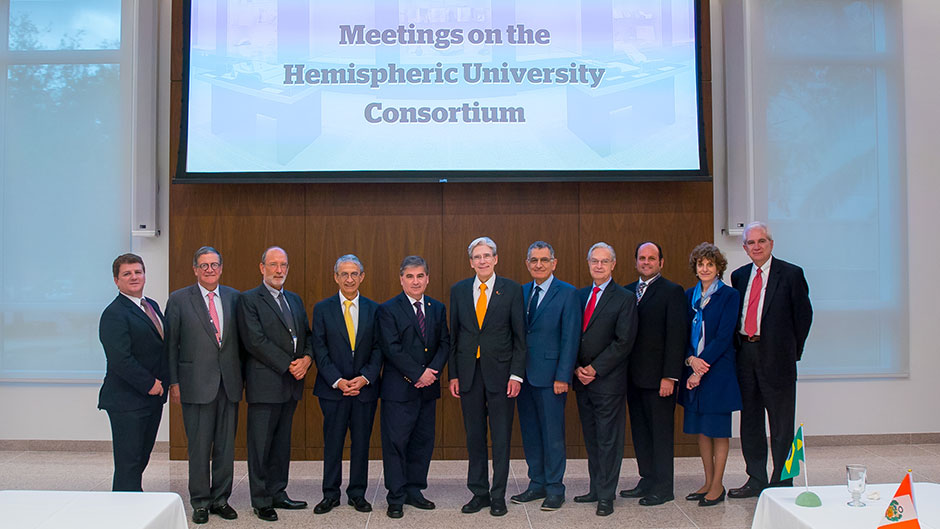

Leaders representing 11 universities across the hemisphere responded to the University of Miami invitation and gathered in Miami on April 23 agreeing to partner in a Hemispheric University Consortium.

The Hemispheric University Consortium, a component of UM’s Roadmap to Our New Century, will provide a platform for the mobility of students, faculty, and researchers to collaborate. The concept is based on the premise that universities—usually the oldest and most prestigious of a nation’s institutions—are together better suited to explore strategies to remedy society’s biggest ills.

“Universities can craft alliances that national leaders can emulate,” said University of Miami President Julio Frenk. “By building bridges based on shared goals, we become stronger than if we faced our future alone.”

As faculty and students are exposed to explore wider and higher opportunities for their development beyond their own geography and culture, said Sir Hilary Beckles, vice chancellor of the University of the West Indies, it is possible to think of a future of where there are “professors for plurality, students against singularity.”

Henning Jensen-Pennington, the president of the University of Costa Rica, highlighted that this consortium initiative of academic and scientific collaboration distinguishes itself as it build ties based on mutual knowledge, strengths, and common languages.

The presidents and vice presidents representing the University of Sao Paolo (Brazil), University of the Andes (Colombia), the University Andres Bello (Chile), Catholic University of Chile, and the University of Toronto, stressed the importance of defining common goals and the key areas of mutual interest, such as technology innovation and health care.

In this way, at the meeting convened by the University of Miami’s president, the leaders agreed to a list of topics that are of great relevance for the hemisphere and the world—public health, climate change and urban resilience, crime and corruption, and entrepreneurship with inclusive innovation—around which they will focus their collaborations.

“Everyone is interested and hungry to share our experiences about innovation in education,” said Raul Rodriguez, associate vice president for international affairs at Monterrey Tech in Mexico. “In terms of topics for the consortium this is a success story—a low-hanging fruit.”

The “homework” for the Consortium members now is to craft the road ahead, as this will determine the strategy that defines their initial joint exercises related to education, research and innovation, focusing on the agreed problem-related topics. In the short-term, they proposed creating an online course that would be offered to the consortium students, and, as “a long-term possibility,” a master’s study program where an academic cohort might rotate from university to university to mine a single topic.

"Crime, money-laundering, drug-trafficking and corruption are very much universal," said Vahan Agopyan, president of the University of Sao Paolo. "As academics, we need to say what we have to say. We will organize workshops [around these topics] through the consortium and have people come to work together."

At a concluding session held at UM’s Kislak Center, President Frenk outlined the consortium framework and offered that the agreement provides the unprecedented potential for deeper levels of engagement between universities and is “inclusive of the entire hemisphere,” in that it includes Canada and the United States, the third largest nation in terms of its Latin American population. UM is “happy and honored” to serve as coordinator, especially in the initial phase,” he said, but emphasized that the consortium “can only work if it’s a partnership of equals.”

Following a discussion to clarify key points of a memorandum of understanding, Luis Ernesto Derbez, president of University de las Americas Puebla, urged the group to action “to capture our willingness to move forward." As a result, representatives agreed that those willing and enabled to sign the agreement do so. Ten universities, including UM, penned their signatures.

They agreed to begin with a gradual strategy, to seek wins in the short-term, then move to intermediate goals that might include certificate programs aimed at the business community. Leaders in the consortium agreed to resolve pending consortium framework issues efficiently and to organize a next meeting within the coming months.

As an important highlight to their meetings, earlier in the day, Consortium members participated in a panel at the eMerge Americas conference titled, “Engines for Innovation: Universities and Innovation Ecosystems in the Americas,” with moderator Andres Oppenheimer, seasoned Latin American journalist with the Miami Herald. Oppenheimer challenged the university leaders that the region lags far behind other global regions in terms of its economic innovation—owing in large part to the “non-alignment” of academia and the business sector.

According to Oppenheimer, the 33 Latin American nations combined for only approximately 1,000 patents last year, compared to thousands in South Korea alone. And Latin American research and development investment as part of GDP stands at only .6 percent compared to South Korea and Israel at 4.5 percent.

Luis Ernesto Derbez, president of University of the Americas Puebla (Mexico), said fostering an innovation partnership, such as that proposed through the consortium, would help to address the situation. “It’s very little money being invested and there’s an adversity to risk—it’s a matter of creating an ecosystem,” he said.

Beckles, of the University of the West Indies, countered that instead of focusing “on this thing called economic growth,” the region in past decades has instead sought to generate social growth. He said then that, “we need both.”

“Our role is to recognize that we can make this change and that, by creating a culture of patenting, in the end we will have more money to invest in social problems,” said Carlos Zamudio, of Peru’s University of Cayetano Heredia.

Participants in the April 23 meeting included presidents, provosts, and vice presidents from the University of the West Indies; Universidade de São Paulo; University of Toronto; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile; Universidad Andres Bello; Universidad de los Andes; Universidad de Costa Rica; Universidad de las Américas Puebla; Tecnológico de Monterrey; Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia; and University of Miami.