Wearing an oxygen mask and neck brace, the teenager is conscious but confused when he arrives in the ER with a paramedic who advises he fell down stairs after swallowing an unknown quantity of antidepressants, opioids, and alcohol in an attempted suicide.

“Help me, please help me,” moans the 17-year-old named Oscar. “Where am I? Why is everything so blurry? Am I wearing 3D glasses?”

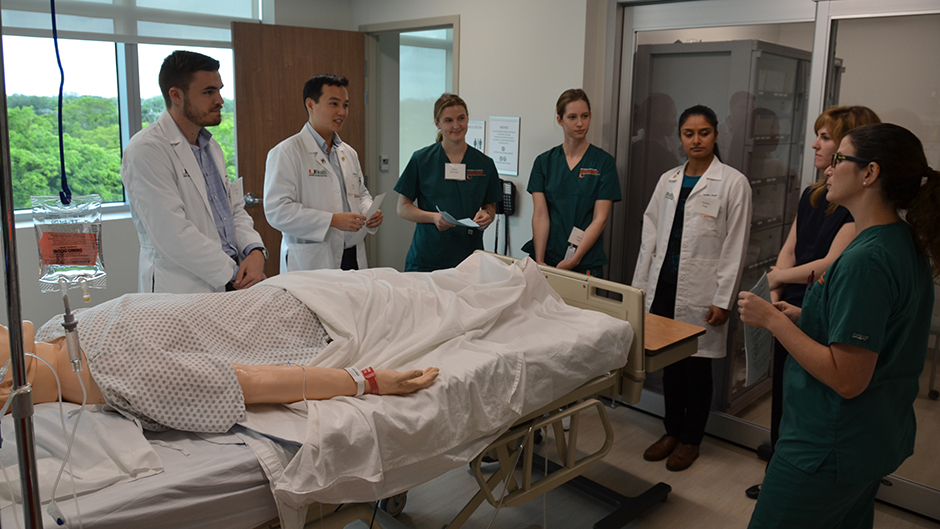

Within minutes, Oscar’s heart rate soars, his blood pressure drops, and six third-year medical students and second-semester nursing students gathered around him act in unison to help. No one, though, notices the signs on the walls with the number to the Poison Help hotline that could have provided step-by-step instructions to stabilize him.

Given the nation’s suicide and opioid epidemics, Oscar’s case is strikingly realistic. But more good than harm was done because Oscar is a high-fidelity mannequin who helped impart the essential lessons that 77 accelerated nursing students and 148 medical students who usually train separately aren’t likely to forget after spending June 18-22 in the University of Miami’s Interprofessional Patient Safety Course.

Established in 2013 by the Miller School of Medicine and the School of Nursing and Health Studies (SONHS), the intense weeklong course is designed to nurture the mutual respect, situational awareness, and communication and team-building skills that future physicians and nurses need to prevent errors and improve patient outcomes in the real world.

“Every patient and every situation is different, so students need to pay attention to both the details and the big picture to develop a shared mental model,” said Mary Mckay, SONHS associate dean for nursing undergraduate programs who was instrumental in establishing the joint training program, one of the nation’s first. “A shared mental model ensures everyone is on the same page and guides patient care.”

This year, one of the new elements of the course emphasized the importance of doctors and nurses developing a discharge plan before releasing a hospital patient. After their ER encounter with Oscar at the Miller School's Gordon Center for Medical Research Education, the teams learned he had fractured his pelvis in his fall and had a history of depression.

With prodding from SONHS instructors, one team quickly realized that Oscar could not return home without crutches, a home assessment, counseling, and other services, including support and suicide prevention education for his family, in place.

“We want everyone to understand that patient safety doesn’t end when you discharge a patient from your care. There are things you need to do to make sure they are safe at home,” said Jill Sanko, an advanced certified simulation educator and SONHS assistant professor who noted that insurers now penalize healthcare providers for patient readmissions. “Part of this is to reduce healthcare costs, but…we need to do anything we can to keep them on the trajectory of getting well.”

With a welcome by Miller School Dean Henri Ford and SONHS Dean Cindy Munro, the course opened last Monday in SONHS’ new state-of-the-art Simulation Hospital with a sobering look at why patient safety has evolved into a vital discipline.

The catalyst, David Birnbach, senior associate dean for quality, safety and risk and director of the UM-Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety, told the students, was a 1999 report by the Institute of Medicine that found more people die annually from avoidable medical errors than from breast cancer, AIDS and car accidents.

The IOM report and other papers that followed jolted the medical world, prompting the Miller School and its partners at Jackson to establish one of the first patient safety centers in the nation. The Miller School soon became one of the first medical schools to require students to pass the weeklong patient safety course, and, joining forces with the SONHS in 2013, to jointly train future nurses and doctors in a series of simulations that are followed by debriefings by faculty from both schools.

“We take this very seriously because it is serious,” said Birnbach, who is also executive vice provost of the University. “Patient safety is incredibly important and doesn’t happen without great teamwork and communication.”

Helping make the experience as immersive, effective, and organized as possible this year was the addition of the expansive 41,000-square-foot Simulation Hospital on the Coral Gables campus.

“The size and layout of the Simulation Hospital allowed us to go from simulation to control room to debriefing room seamlessly, without losing the continuity of the thought process or the experience,” said Jeffrey Groom, SONHS associate dean of simulation programs. “It also has clinical and patient rooms that look appropriate to the scenario, providing a more realistic physical context than in previous years.”

Assigned to six-person interdisciplinary teams, the 225 students started their week at the Simulation Hospital trying to piece together a tricky table puzzle. Then they moved on to an escalating series of simulated patient encounters—with both high-fidelity mannequins and “standardized patient” actors—to elicit the observations, questions and interactions that enhance communication and teamwork and avoid mistakes.

Reintroduced this year is the unique way UM's course incorporates the humanities—in collaboration with two of the U’s renowned artistic institutions—to reinforce the same lessons in different and innovative ways. Attending the Lowe Art Museum’s workshop on “The Fine Art of Healthcare” on Wednesday, the students viewed and discussed different works of art to practice conveying their impressions and incorporating the perspective of others—a process critical not only to interpreting art but making proper diagnoses.

Later that afternoon, they watched a video of the perfectly synchronized members of the Frost School of Music’s Henry Mancini Orchestra perform a beautiful rendition of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor. Then they heard how discordant the piece sounded when a lack of leadership and teamwork wrecked the masterpiece.

By Thursday, as each team encountered Oscar at the Gordon Center, most reacted to the mannequin’s rapidly deteriorating condition by joining forces, discussing options, and delegating tasks. And while most participants overlooked the signs for Poison Help, not many are likely to miss such important details in the future.

“It’s been such a fascinating week because we are learning what their (the nurses’) roles are and how they contribute and how we contribute, which we haven’t had,” said Meera Nagarsheth, one of the medical students who begins rounding on real patients this week. “The best thing for me is it makes me go back to the basics. Instead of medicine, what this week has taught me is the importance of just being in the present.”

While the course culminated on Friday with the SimOlympics, in which the two most improved teams took on an identical medical emergency simulation as their peers observed and cheered, nursing student Stephanie Nwadike was ready to do it again.

“I loved it,” said Nwadike, who began seeing patients almost from day one of the 11-month Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing program. “From the first simulation to the last, I could see a big improvement in my own communication and situational awareness skills."