Being No. 1 may be a point of pride when discussing football, but greater Miami finds itself in the unenviable position of leading the nation in two categories that, one day, could make living here impossible for many residents.

Not only does greater Miami have the nation’s highest percentage of renters who spend more than half of their income on housing, but the metropolitan area also has the most property vulnerable to rising seas.

To address both housing challenges together, the University of Miami’s Office of Community and Civic Engagement (CCE) has received a new $300,000 grant from JPMorgan Chase & Co. to expand its Miami Housing Solutions Lab to visualize the projected impact of rising seas on South Florida’s 43,000 multifamily affordable housing units and to recommend modifications that could protect them from flooding and other extreme-weather conditions.

“Conversations about affordable housing and sea-level rise have typically happened parallel to one another, but not in concert with one another,” said CCE Director Robin Bachin, UM’s assistant provost for civic and community engagement. “The goal of this grant is to address these two vexing problems together by understanding better ways through policy solutions, adaptation, and mitigation to build an affordable, resilient, urban infrastructure in the face of climate change and sea-level rise.”

A longstanding supporter of CCE’s affordable housing initiatives, JPMorgan Chase is enthusiastic about advancing the new proposal,Housing Resiliency and a Sustainable South Florida, not only to address both regional problems simultaneously but to serve as a model for coastal cities nationally and globally.

“South Florida already has one of the nation’s highest rates of cost-burdened renters and greatest shortage of affordable housing,” said Maria Escorcia, the JPMorgan Chase Foundation’s vice president and program officer for Florida. “With rising sea levels, it is critical that we fully understand how vulnerable these units are and develop solutions to address this issue head on.”

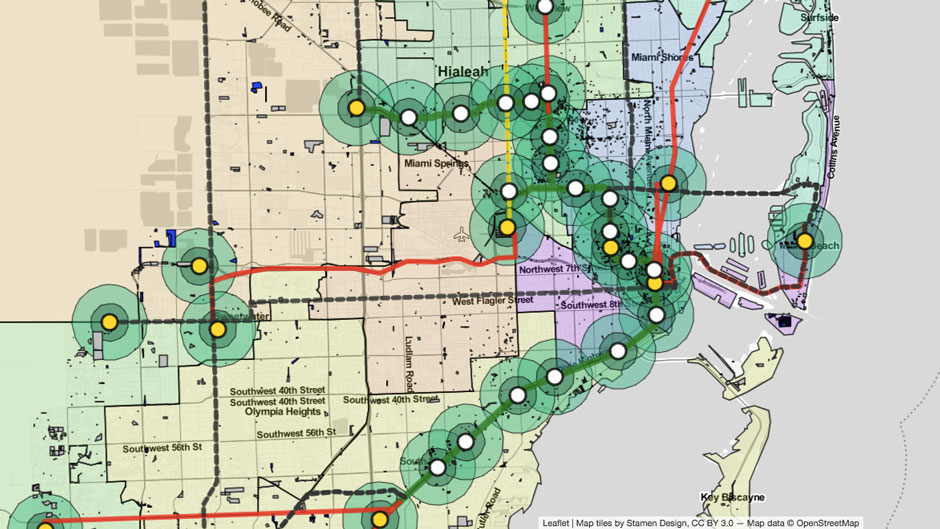

CCE will use the grant to add a new layer to its Miami Affordability Project (MAP) tool to show the projected impacts of sea-level rise on subsidized multifamily rental housing units. It also plans to expand its Miami Housing Policy Toolkit to include neighborhood-level sea-level rise mitigation and adaptation solutions.

A first-of-its kind, open-access, research tool with more than 200 filters, the MAP combines local, state, and federal data on affordable housing to enable users to visualize the distribution of affordable housing, housing needs and cost burdens across South Florida. Created in 2015 in collaboration with UM’s Center for Computational Science, and with funding from JPMorgan Chase and the Jesse Ball duPont Fund, the MAP has been enhanced and expanded over the years, and already has helped countless planners, policymakers, developers, community organizations, and researchers encourage data-driven affordable housing analysis and solutions.

For example, Miami-Dade County’s Department of Public Housing and Community Development relies on the MAP to allocate its federal affordable housing funds. And the South Florida Community Land Trust is using the tool to identify publically owned land suitable for developing affordable housing. They are among the many entities that welcome the MAP’s expansion to include the projected impacts of sea-level rise.

“Inherent in the land trust model is keeping affordable housing affordable forever so we look at long-term solutions to the affordable housing problem,” said Mandy Bartle, executive director of the land trust, which builds and sells affordable housing on land permanently held in trust. “If we have a long-term approach to keep affordable housing affordable we also need a long-term approach to make sure we are keeping affordable housing afloat.”

In concert with the MAP’s expansion, the CCE plans to bring experts from UM’s College of Engineering, College of Arts and Sciences and School of Law together with local stakeholders to develop strategies for retrofitting existing low-income housing that is vulnerable to rising seas. They’ll start by identifying four multifamily housing developments for further study. The team also will advocate for housing policies and practices in South Florida that encourage the maintenance and development of affordable and resilient housing.

Solving social problems by connecting community partners with UM’s multidisciplinary faculty and diverse student body is key to the CCE’s mission, which, at its core, is to prepare students to contribute to the well-being of their communities.

Since its founding in 2011, CCE has facilitated dialogue and action on a number of issues, but particularly on local housing, development, and revitalization. As of 2017, 46 emerging scholars have taken part in its Community Scholars in Affordable Housing Program, a partnership with the South Florida Community Development Coalition and Catalyst Miami, to recruit emerging leaders to the affordable housing issue. One day soon, they will likely use the MAP to address the perils rising seas pose to affordable housing. JPMorgan Chase also supports the community scholars program.

With an expansion grant from JPMorgan Chase’s philanthropic foundation, CCE enhanced the MAP’s capabilities to include geocoded housing and census data for most of South Florida, including Broward and Palm Beach counties, as well as new parcel-level data for additional neighborhoods facing growing redevelopment pressure in Miami. It also expanded the MAP’s historic layer, enhanced its interactive Housing Policy Timeline that charts the history of housing policy at the local, state, and national levels, and created a policy toolkit that outlines innovative strategies for promoting affordable housing.

As the land trust’s Bartle notes, developing and maintaining affordable housing in South Florida is a daunting challenge, making the data-driven information the MAP provides essential to nonprofits like hers. Without it, she said, the land trust would have to sift through thousands of individual property records in dozens of cities to locate publically owned land that is near good jobs and good public transportation—among the trust’s criteria for acquiring public lands to build affordable housing.

“It would be a very intensive amount of work and the fact that they’ve already done that initial heavy lift is a huge asset,” she said. “Now having this additional information about resiliency could help us further prioritize areas that are high on our opportunity index. If I know a neighborhood is on low-lying grounds I know I might have to build houses there differently. It may end up dictating the design of the house itself.”