1968.

It was a year unlike any other, one marked by tragedy and turmoil with one traumatic event following another.

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was cut down by an assassin’s bullet in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, igniting riots across the nation. Shortly after winning the California presidential primary, Senator Robert Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in the early morning hours of June 5. He would die a day later.

President Lyndon B. Johnson declined to run for office again. Tens of thousands of Vietnam War protestors clashed with police on the streets of Chicago at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. And there were also protests in the streets of Paris, Prague, and Mexico City.

Fifty years later—in the wake of a Florida man being arrested and charged for mailing pipe bombs to prominent Democrats, including Barack Obama, and a 46-year-old man accused of slaying 11 worshippers at a Pittsburgh synagogue—many Americans see 2018 as a repeat of 1968.

But is history, indeed, repeating itself?

With voters preparing to cast their votes in the critical midterm elections on Tuesday, News@theU asked four University of Miami professors who were all college students in 1968 to give their perspective on the parallels between the two years and whether the nation is hopelessly polarized.

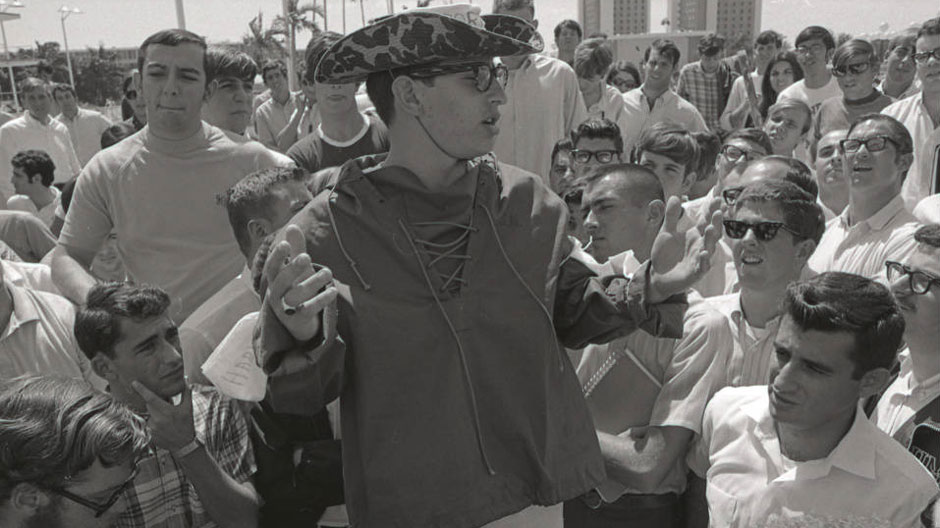

THE POWER OF PROTESTS

Once suspended from tiny Edward Waters College in Jacksonville, Florida, for organizing and leading what school administrators deemed were too many protests that disrupted the campus, Marvin Dawkins knew in his heart that he was actually “doing the right thing”—that he was part of a legion of college students nationwide who were “only trying to raise the social consciousness of everyone,” he said.

“I was an activist in the true sense of the word,” said Dawkins, now a professor of sociology in UM’s College of Arts and Sciences. “I was involved not only in activities on campus but off as well.”

He faced a pivotal moment in his life after learning via a radio broadcast that King had been assassinated. Like many African-Americans, he was heartbroken and angry. “Some of my friends wanted to go downtown and riot,” he recalled. “I was torn. I didn’t know whether to follow them or to go to campus. I decided, largely because of my mother and father, to go to school.”

It was a decision that ensured his passion for activism would live on. Even as a student at a summer scholars program for minority students at Columbia University in 1968, Dawkins kept that passion ignited, attending Black Panther rallies and marching through the streets of Harlem.

“I saw the strife that existed nationally, how much turmoil the nation was in,” he said. “I didn’t want to stand on the sidelines.”

The year 2018, he said, “is like déjà vu.”

“I remember the nightmare that was going on in ’68. It didn’t seem like things would turn around and improve. Only clouds ahead,” said Dawkins. “That’s the similarity I see with today. Bombs being sent to people simply because of their political stance. Mass shootings. It just looks like we’re headed into a period of darkness. But 50 years of hindsight has taught me to believe in something that Jesse Jackson always said: Keep hope alive.”

SNIPERS ON THE ROOF

School of Law Professor David Abraham was an undergraduate at the University of Chicago in 1968, living and studying in the middle of the Windy City’s so-called Black Belt.

Abraham remembers it all: armed sharpshooters on the roof of his apartment building during the civil disturbances that followed King’s assassination. Tear gas. Tanks on the streets of Chicago.

“The year was extraordinarily tumultuous. Every moment was one of extreme tension and expectation,” he said. “But despite leaders being killed and cities burning, despite the endless deaths in Vietnam, there was a certain optimism. There was a sense that history was on our side, that it was moving forward. The civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, the beginnings of a feminist movement, as we came to know it later—all those things were happening. In the aftermath of the King assassination, we were marching and marching forward.”

Today, Abraham sees symptoms that indicate how divided the nation is. “But I don’t see the optimism of 1968. What I see is that today in the period of neo-liberalism and the end of socialist economic strivings, we have split apart that which Martin Luther King tried to bring together. We have identity politics, gender politics, a great concern with disparity. But not that much of a commitment to fighting social inequality.”

The midterm elections, he said, “are about the possibilities of maintaining the fundamental elements of liberal democracy. They’re not about moving forward. They’re about preventing disaster.”

THE ABSENCE OF A UNIFYING THEME

During the ’60s, Professor of International Studies Bruce Bagley was at ground zero for the student protest movement of that time—first at the University of California, Berkeley, and then at UCLA, participating in demonstrations on both campuses. He joined the Peace Corps in 1968, spending nearly three years in Colombia.

Bagley recalled the widespread dismay and dislike among students for the war in Vietnam. “From my perspective, there was a uniting ideology of opposition to the war in Vietnam. But it also had an underlying theme. It touched on relatively affluent white middleclass students,” said Bagley. “The difference today is that there’s no unifying theme. There’s no massive civil rights movement in this country among students or anybody else, and there’s no massive protests against any of the wars that we’ve been involved in.”

President Trump’s brand of politics has polarized the country, said Bagley. “But we can’t blame it all on him, because this society is confronting major problems that we have not addressed. There is no question that there have been both winners and losers in the processes of globalization that this country experienced throughout the 21st century.”

A STATE OF DIVISIVENESS

Distinguished Professor of History Donald Spivey, who teaches a course on the ’60s, was a running back on the University of Illinois football team in 1968, and as a student “we were in midst of all kinds of struggles, as everyone else across the country was,” he recalled.

Spivey decided to hang up his cleats, committing himself fully to academics and social causes. He became a member of the black student association at the university, leading an effort to get the school’s history department to hire a black faculty member. “They had no faculty of color,” said Spivey, “And this was all happening alongside the tumultuous events of that year—the assassinations, the demonstrations against the war. There wasn’t a more active time for being pulled in a thousand different directions and being urged to grow up and take a stand.”

He describes the America of 2018 as being in a state of divisiveness, a nation polarized along party lines. “I thought ’68 was bad. But if someone had told me I would eventually see something like what we’re seeing today, I would have told them they were wrong.”

He calls the upcoming midterm elections the most important in American history. “If we don’t get a Democratic Congress that would put some kind of checks and balances on this administration,” said Spivey, “things could get worse. America as we know it will completely die.”