Robert Latham did something no one else has done. The associate director of the Children & Youth Law Clinic built an interactive website mapping the placements of every single child who passed through Florida’s Department of Children and Families since 2002.

When the former senior program attorney for the Guardian ad Litem program requested the information from DCF in 2017, he was not quite prepared for the deluge of information. The spreadsheet contained almost 300,000 records, 77.8 million data points, and included children in foster care going back into the 1980s.

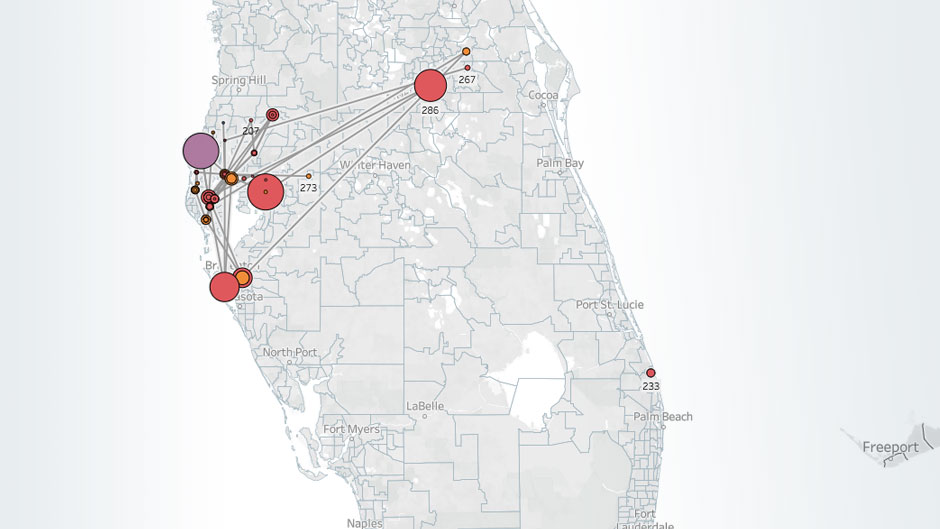

“We are used to seeing written lists of their placements,” Latham said, “but to see the actual journey in a map was something I had never seen before.“

Digging into Stability of Foster Care Placements

The project started when the clinic attorneys decided to dig into placement stability, where kids go into foster care and stay in a stable home as opposed to bouncing throughout the system from home to home to home. They were only finding aggregate numbers – average numbers of placements – in the state’s public system, so Latham asked for all the data.

“I received a spreadsheet that was over a million lines and almost every single line was a kid being dropped off at a new house,” said Latham who earned a B.S. in computer science from the University of Texas. “It was just jaw-dropping. I couldn’t get my head around it that they had this information going back to the 80s and 90s.

“After playing with it for a year,” he says, “I realized that I had zip codes and I had latitude and longitudes so I could build a map. I started looking for patterns, and the easiest patterns were distinguishable traits – like, sadly, kids who had died in foster care or were involuntarily committed, or kids who had 10 or more placements – identifying those kids would be research-worthy.”

Finding Patterns Within the Data

“It got a lot of responses. One response was that it got people talking about how foster care is used,” Latham said. “One thing that came out was the ‘night-to-night’ placements, where a foster parent is contacted, usually after hours, and asked to take a child for just one night. What the map shows is that same thing might have happened for more than a dozen nights in a row for that child with different foster parents.

“It also shows where children may have passed through houses where terrible things happened as was the case in Sarasota. DCF doesn’t share this information with later foster or adopted parents, so that is one of the ways the map is being used,” he said.

(A foster father was charged with sexually abusing children in his care. Gilberto Rios committed suicide last month during his trial on sexual battery of a child less than 12 years of age. Using the database, the Sarasota Herald-Tribune was able to contact foster and adoptive parents to notify them of what their children had been through.)

Florida Public Records Law – Key Factor in Amassing the Information

One reason Latham could build the map was thanks to Florida’s public records law, one of the broadest in the United States, and the impact has been widespread. “It is helping people understand the child welfare system at the kid-by-kid level in a way that you could not before,” Latham says.

“Before, it was just anecdotes: one kid that had a particularly compelling story with a really beautiful picture of them or aggregate data that just globs all the children together into one big pile where you can never tell what is going on. This ties the two together.”

The next step is focusing on the placement side and red flagging problems, such as homes with higher than average numbers of children, or homes where children get arrested or taken into custody as being a danger to themselves or others at higher rates.

Latham is also looking at home where a high number of children run away for the first time as this might indicate that the caregiver may not be a suitable foster parent.

Background in Computer Science Aids in Data Digging

Many factors have helped bring this project to fruition, both Latham’s tenacity to protect youth plus his undergraduate degree in computer science coupled with a love of data.

Bernard P. Perlmutter, co-director of the Children & Youth Law Clinic agrees, “Robert Latham’s mapping project reflects both his ingenuity and fascination with data and his deep interest in the welfare of individual children in Florida’s child welfare system. It is far more than an exercise in statistical analysis, but a careful look at how foster children drift through and get lost in the system, whether due to frequent foster care placement shifts, being locked up in mental health facilities, or crossing over to juvenile and adult incarceration.

“In my three decades in this field, I have never encountered a more incisive or compelling exploration of the cold data to reveal the instability of children’s lives in foster care. Already the mapping has helped to identify systemic problems and federal constitutional and statutory violations in the most populous region of the state, the DCF Southern Region -- Miami-Dade and Monroe, which a recently settled federal class-action lawsuit, H.G. v. Carroll, is attempting to remedy."

More on the Children and Youth Law Clinic