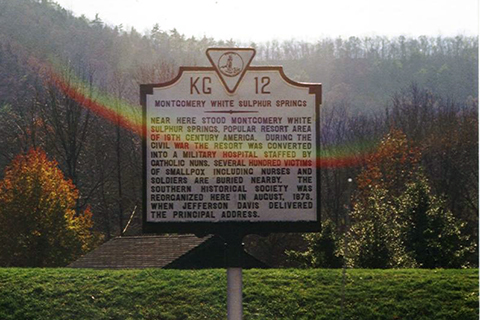

While exploring the Virginia countryside 30 years ago, Cindy Munro stumbled upon a historic road sign marking a spot where nurses cared for Civil War soldiers infected with smallpox. Hundreds were buried nearby.

Reading the marker gave Munro, who was in her first nursing faculty position at a nearby college, goose bumps. Recalling the sign three decades later—as National Nurses Week opens today and culminates May 12 with a celebration of Florence Nightingale’s 200th birthday on International Nurse’s Day—the dean of the University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies still gets goose bumps.

“I can only imagine what it would have been like to care for smallpox victims in the middle of a war—with no way of preventing or effectively treating the infections,” Munro said. “Clearly those nurses understood what the threats to their own life and safety were, but patients needed them, and they went right on in—which is what nurses have always done.”

That’s exactly what the more than 200 nursing and public health students who will graduate from the University of Miami this week are prepared to do—even amid, or perhaps especially amid, the coronavirus pandemic that is highlighting the critical roles nurses fill.

The irony of that growing respect is not lost on Munro, who previously had pledged her school’s support for an international campaign known as Nursing Now. Launched in 2018, the three-year initiative was designed to improve health globally by raising the profile and status of the world’s 20 million nurses at a time they were facing the rising burden of chronic diseases, shortages among their ranks, and, too often, little understanding of what they do.

In an interview, Munro discussed the irony, her thoughts about the future of nursing, and her pride in the profession that has been stepping up since Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, saved countless British soldiers by implementing sanitation and other infection-control measures at the onset of the Crimean War in 1853.

In an interview, Munro discussed the irony, her thoughts about the future of nursing, and her pride in the profession that has been stepping up since Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, saved countless British soldiers by implementing sanitation and other infection-control measures at the onset of the Crimean War in 1853.

Could you have ever imagined that this next week, which was supposed to be filled with celebrations for graduating students, for Florence Nightingale’s 200th birthday, and for nurses who are seldom appreciated for what they do, would be eclipsed by a pandemic?

It’s really sad that we’re not able to have graduation ceremonies or any of the other celebrations we planned. But we certainly are getting the exposure about what nursing is about and why nursing is so desperately needed. It’s a tough way to learn that lesson. But if any good comes from this, maybe that will be it.

Among the themes for National Nurses Week is compassion, expertise, and trust. In light of the new demands and stresses on nurses, wouldn’t you add courage to the list?

Courage has always been a defining characteristic of nursing. We have a long history of stepping up during pandemics, during wars, during any kind of major disaster. Think of that marker in Virginia, commemorating nurses who took care of soldiers with smallpox during the Civil War. The same with the Spanish flu that swept the world in 1918 and with polio. It was nurses who managed patients in iron lungs—which were sort of the original ventilators. We don’t see polio much anymore because we have a really good vaccine, but it disrupted how people lived in the 1950s. More recently, nurses cared for patients with HIV when no one knew how it was transmitted and when there were no good treatments for it. I think people forget how volatile that time was and how much danger nurses felt—but they still stepped up and did it. We have a history of doing this and doing it well. So, it’s not anything new.

What about the students who are graduating this week? Are they eager to go out into our changed world or having second thoughts?

I really haven’t heard anyone say, “In light of COVID-19, I really don’t think I’d like to be a nurse.’’ Most of the students I talk to are eager to get out there and make a difference. They have had a long time, as students, to get deeply invested in the profession. It’s not the world that they envisioned when they got invested, but we’ve always had patients with infectious diseases, and we’ve always cared for them. So, this is a novel pathogen, but it’s not a novel situation for nurses. The first thing that any nurse learns—the very first thing—is how to protect themselves and others from transmission of infection. The importance of handwashing, of wearing gloves, of how to don and doff personal protective equipment—all of that happens very early in nursing education. Our students are as prepared as possible to move into clinical settings and to prevent transmission of infections.

But aren’t they worried about the job market?

They are worried about the job market, as I think almost all college students are right now. But I don’t have a long-term concern for the future of nursing. Right now, the health care system is so consumed with COVID-19 that many latent needs aren’t at the forefront. But, at some point, we are going to be able to start thinking again about how to take care of patients with diabetes, with new babies, with heart disease, or patients who just want wellness advice. All those needs are still there, and when they return to the forefront, it will be nurses who will provide that care.

What strikes you most about faculty members who are working in area hospitals, on the front lines in the war against COVID-19?

I think there is a lot of pain for nurses when patients don’t survive. But the thing that really strikes me is how much joy they feel when they have a patient who recovers. When they have spent a lot of energy taking care of a patient; when they’ve done a good job; when they see the patient respond, improve, and leave the hospital, they are full of joy.

Many of the school’s faculty members are working in ICUs, where the incidence of ICU delirium among patients, which you study, is said to be on the rise. Did you anticipate that?

When you think about what happens in the ICU, it’s not at all surprising that delirium rates are reported to be high in these situations. You have all these patients who are really isolated experiencing new and unusal environmental stimuli. They may have a machine breathing for them, one circulating their blood, and all these completely foreign sounds and smells that make it very difficult for patients to process. On top of that, their oxygen levels are often not very good, so their brain is a little foggy to begin with—all at a time when nurses have to limit their time at the bedside to reduce the risk of cross-infection.

Nurses are also standing in for family members, who aren’t allowed to visit hospitals, much less ICUs. Doesn’t your current study aim to address that very situation?

Yes, our intervention involves having a family member’s recorded voice at the bedside to help their loved one figure out what’s happening to them in the ICU. But all non-essential research was halted in the ICUs, so our study is on hold for now. I certainly understand that, but I think our intervention would have had some benefit for them, particularly when their family members can’t be there.

The School of Nursing and Health Studies will host its Spring 2020 Awards Ceremony this Friday, May 8, at 10 a.m. EDT via Facebook Live.