Photos of tear gas canisters exploding, yellow umbrellas unfurled as a sign of protest, and flag-waving independence seekers being arrested by police in riot gear have been daily fare in Western news media for over a year. This initially came as a shock, since for so long Hong Kong had been considered a safe and peaceful place amid the often-tumultuous events elsewhere in Asia.

Known as the Pearl of the Orient, Hong Kong long attracted shipping companies, tourists, and investors with its expansive harbor, beautiful scenery, and hard-working population, supervised by an efficient British colonial administration. In the course of a century, Hong Kong grew from an insignificant fishing village to Asia’s second most prosperous city, after Tokyo. Per capita incomes were actually higher than those in the mother country.

So, when Great Britain and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) began to negotiate Hong Kong’s return to China, there was great apprehension. The Sino-British Declaration of 1984 promised a high degree of self-government for the former colony. Under a “one country, two systems” formula, Hong Kong would be a Special Autonomous Region (SAR) of China. Property rights and contracts would continue to be honored, and the judicial system, based on British models, would be maintained for at least 50 years. As an international treaty, the declaration was duly registered with the United Nations.

Certainly, there were grounds for concern. At Beijing’s insistence, the people of Hong Kong were excluded from the negotiations. And the political system it insisted on was anything but democratic; elections would be held but based on a formula that virtually guaranteed Beijing’s preferred candidates would be chosen. The first governor was the head of a major shipping empire with a good reason to be loyal to the PRC—its government had bailed out the company during a financial downturn. Even this could be considered hopeful as a portent of good relations between communist China and capitalist Hong Kong. Hong Kong was valuable to the PRC as a gateway to investment in the then-burgeoning Chinese market. Surely Beijing would not want to kill the goose that laid golden eggs. And in the early 1980s, hopes were high that an economically more prosperous China would evolve into a liberal democratic state. Beijing promised that in 2017 a new political system would allow one person, one vote.

At first things seemed to be going well, but there were a few problems. A gangster who was a legal Hong Kong resident was apprehended and sentenced in China rather than, as he should have been, in Hong Kong. But his guilt was not in question, and the case aroused little sympathy. When the PRC’s National People’s Congress overruled Hong Kong’s Court of Final appeal on whether the mainland-born children of Hong Kong residents had the right of abode in Hong Kong, there was a good deal of grumbling that the latter was now the “Court of Not Quite Final Appeal.” But these were fairly minor matters. Not until 2003, when Beijing tried to impose a national security law on Hong Kong, did serious but peaceful protests begin. The law was withdrawn. Likewise, in 2012 an attempt to impose the teaching of “patriotic education” in the school system, which critics decried as brainwashing, was stymied by peaceful protests.

Then, in 2013-2014, it became clear that Beijing’s idea of universal suffrage differed significantly from that of many Hong Kong residents. The chief executive would be chosen from a slate of candidates chosen by at least 50 percent of the members of a nominating committee, and no candidate could work against the state or be open to foreign influence. In the words of one pro-democracy activist, the choice would be between two slightly different shades of Beijing-chosen vanilla. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in a three-month long Occupy Central movement, with pro-Beijing supporters arguing that Hong Kong’s economy was being destroyed and that, given the central government’s intransigence, the choice was between accepting the government’s half a loaf or continuing the present system. The demonstrators surrendered, with a 17-year-old firebrand, Joshua Wong, emerging as a leader who was willing to go to jail, and did, on behalf of his principles.

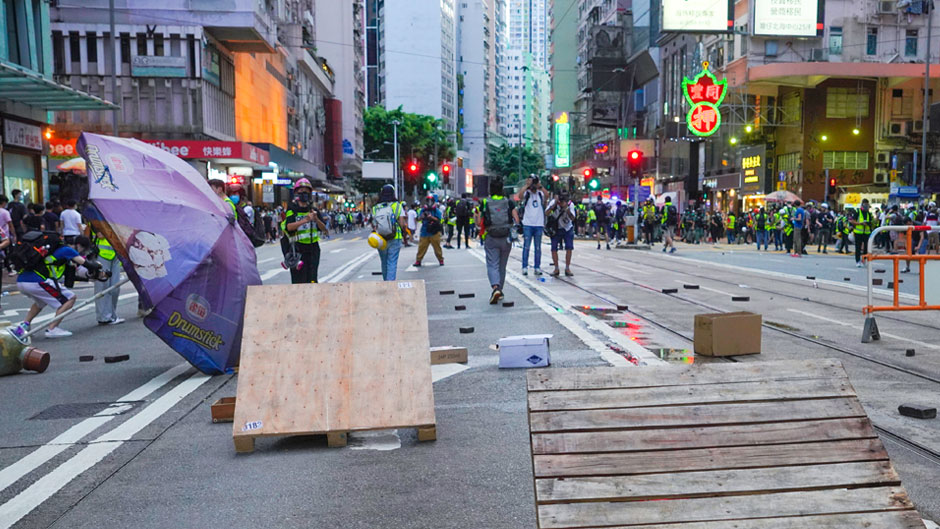

The current situation derives from an extradition bill, under which Hong Kong permanent residents could be extradited to China, thereby exposing them to incarceration under the PRC’s draconian and corrupt legal system and infringing on the civil liberties that had been promised to Hong Kong. Chief executive Carrie Lam refused to withdraw the bill, leading to escalating protests and attacks on the protestors by gangs believed to have been instigated by pro-PRC forces. The heretofore peaceful protestors fought back, with numerous injuries, several deaths, and great property damage. As many as two million people out of a total population of seven million took part. By the time Lam withdrew the bill, the protestors had new demands, including the appointment of an independent commission to investigate rights abuses and genuine implementation of one person, one vote in the election of the chief executive and legislative council.

An uneasy calm induced by the coronavirus pandemic ensued. This appears to have convinced Beijing that the time for the next move had arrived—in the words of a traditional saying, “after the harvest, settle accounts.” In direct contravention of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, stipulating that such laws are to be enacted by the Hong Kong government, Beijing passed a national security law providing punishments up to life sentences for vaguely defined crimes like secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces—with itself as judge. Pro-democracy groups disbanded, and numerous books, including those of the now-23-year-old Joshua Wong were either withdrawn from libraries or listed as “under review.” The outcome of elections scheduled for September is no longer in doubt, since Beijing will be able to declare candidates who “do not love the motherland” unacceptable.

Beijing has also pressured numerous foreign corporations—including the London-based banking giants Standard Chartered and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation—to declare support for the law, which, they dutifully declare, will make Hong Kong safer. So, too, have Chinese diaspora communities. Some businesses have vowed to leave the SAR; others, more constrained in their ability to move, have decided on a policy of watchful waiting. Beijing appears to have achieved complete victory. Asked whether the protests were in vain and the Pearl of the Orient was facing its end, a long-time democracy advocate replied that the Hong Kong people know that the road to freedom is long and hard, adding, “It is not that we see hope and therefore we persist; it is that through our persistence, hope is created.”

June Teufel Dreyer is a professor of political science in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences. An internationally renowned authority on China, she teaches courses on U.S. defense policy and international relations and is a senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a member of International Institute for Strategic Studies.