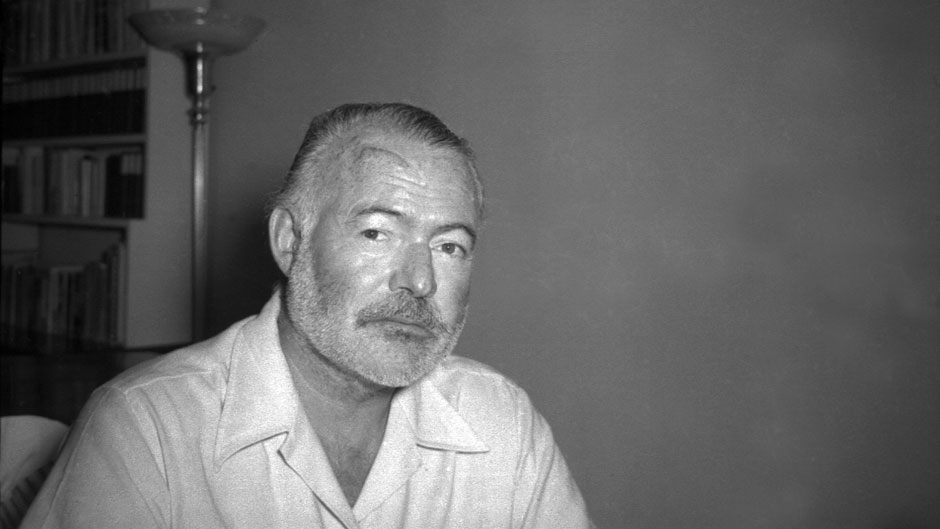

The winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and drama in 1953 and for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, Ernest Hemingway was revered, mythologized, and imitated by writers and readers in the United States and indeed around the world for much of his lifetime and for decades after.

Others in the writing world, however, have long criticized “Papa’s” machoistic and misogynistic themes and tendencies.

“There is a way that Hemingway’s voice represents the men of an era, but I don’t think we cancel that—as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color writers and women of color, we take note of it,” said M. Evelina Galang, a professor in the University of Miami’s MFA Creative Writing Program and a former program director. “His voice and his attitude toward women in particular are something worth documenting and understanding if we are to make room for the multiple voices that arise from the inclusive practices of reading, writing, and publishing widely.”

Galang said that her first story collection included interstitials—intervals or intervening spaces—that were clearly influenced by her reading of Hemingway’s “The Nick Adams Stories,” a volume of short stories published in 1972, a decade after his death by suicide in 1961.

Filmmaker Ken Burns—who has explored elements core to U.S. culture from the Civil War to jazz to baseball—together with co-director Lynn Novick recently featured the celebrated writer in their six-hour documentary “Hemingway: The Man. The Myth. The Writer Revealed,” which aired on PBS.

“I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across—not to just depict life or criticize it but to actually make it alive. So that when you’ve read something by me you actually experience the thing,” Hemingway once said.

“Ernest Hemingway remade American literature, he pared storytelling to its essentials, changed the way characters speak, explored the worlds a writer could explore, and left an indelible record of how men and women lived during his lifetime,” the film noted.

“His voice and his manner were quick, accessible, and no-nonsense,” Galang pointed out in highlighting Hemingway’s particular style. “He got right to it and gave just enough detail to give you a sense of what he was talking about without telling you everything. He left out plenty and that, too, was part of his style.”

That sparse, stark style heightened the impact, she explained, and referenced one of Hemingway’s best known short stories, “Hills Like White Elephants.”

“The story stayed with you, you thought about it long after it was over,” Galang said. “You made sense of what was there, and it was the not knowing that kept the story with you.”

Joel Nickels, an associate professor in the English Department and director of Undergraduate Studies, teaches several Hemingway stories in his literature classes.

The short declarative sentence—so emblematic of Hemingway—is unique to him and not reflective of any particular American vernacular mode of speech, according to Nickels. He suggested that Hemingway’s austere, minimal style reflects the mindset of a generation that suffered severe trauma and whose mental processes had returned to a very simple, straightforward mode of processing data.

“It’s as if, spiritually speaking, an entire generation has been hit by a board and is dazed, attempting to reconstruct a sense of investment and belief that is credible,” said Nickels.

Nickels referenced "Soldier's Home," a story he teaches every year. “It's clear that the stark repetitions Hemingway includes are meant to represent the war trauma of the story’s main character, Krebs—that he has been returned to a very basic modality of processing sense stimuli because he's unable to express his feelings about his experiences during World War I,” he noted.

The associate professor said that his students often make the connection between Kreb’s mental state and what, nowadays, we refer to as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Talk therapy was still pretty rare in the U.S. in the years immediately following World War I. So, there's no real venue for a war veteran such as Krebs to talk about the ways his value system, sense of identity, and spirituality may have been affected by his wartime experiences,” Nickels stated.

He added that the same is true in “The Sun Also Rises.”

“Hemingway's very basic style seems to reflect a traumatized hostility to any form of sentiment, which I believe he associates with the kinds of ideological manipulation embodied by state-sponsored wartime propaganda efforts,” Nickels explained. “It's as if his characters are temporarily taking a break from all forms of spiritual investment, because they feel betrayed by a propaganda industry that billed WWI as a Great War for civilization rather than as what many members of the Lost Generation came to believe it actually was: an imperialist war of rival capitalist powers fighting for markets, colonies, and dominance over the international banking system.”

Hemingway, together with Gertrude Stein, T.S. Elliot, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, were among the post-World War I writers called the Lost Generation, a fun group of writers who immigrated to Europe where they wrote, lived, and partied extravagantly, Galang pointed out. Hemingway’s memoir “A Movable Feast” documents their historic life of literature and debauchery.

The documentary suggested that Hemingway’s three decades of writing and publishing acclaim “changed the furniture in the [literary] room, and that generations of writers who followed him either killed his ghost or embraced it but none could escape it.”

“I think he took furniture out of the room, and that he didn’t have enough seating,” Galang commented. “Sometimes, the way he arranged the stuff was sparse and uncomfortable. That’s OK as long as it was intentional and inviting to the mind, which oftentimes it was. Yet, there are many of us who read him and don’t see a seat in that room for us.”

Galang noted the criticism of Hemingway for “his misogynistic portrayal of women.” But said that she and other writers can and should still learn from Hemingway’s literary landscape.

“So often today, those who are writing from a perspective and time that we would now call offensive and oppressive—and someone cancel culture would definitely erase—are really just reminders of how much has and has not changed. We need these stories, in this case by Hemingway, to mark the way humanity has shifted, progressed, and remained stuck,” Galang said.

“We writers learn from their craft,” she said. “We reinvent and revise our ways of storytelling—dismantle the master’s house as it were—by understanding the way the story was built. We learn to do better. I love that.”