Arthur Dunkelman’s presentation, “Reefs, Wrecks, and Rascals: The Pirate Legacy of the Spanish Main,” delivered virtually on Thursday afternoon, marked the eighth edition of the University of Miami Libraries’ Deep Dives Series that highlights Special Collections’ materials.

The curator and historian complemented his talk by displaying a range of rare manuscripts, books, and other extraordinary artifacts held in the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Early Americas, Exploration and Navigation, one of the Libraries Special Collections donated to the University in 2017.

He explained that his interest in commerce, trade, and economic history and his work with the Kislak Foundation merged to offer a golden opportunity for him to delve into an exceptional historic era in the Americas.

“Piracy has always fascinated me because it’s the integration with real life, fantasy, and history,” Dunkelman said. “I’m especially interested in the development of trade and how pirates have played into the economic history of Europe and the Americas, and how these individuals were manipulated for financial gain and political power by men of even greater power and influence and how they worked for and against nationalities and become interwoven in the fabric of the history.”

In a deep linguistic dive, Dunkelman marked the difference in terms associated with piracy. Buccaneers were named for the “viande boucaneé,” French for the smoked meat sold to the ships for basic diet. Privateers were captains and crews licensed first the French, and later by the English and Dutch, to prey upon the Spanish flotas—a fleet of ships transporting treasures from the Americas.

The Dutch referred to pirates as sea rovers and the French as “adventurous filibustairs”—a historical meaning used for someone who engages in authorized warfare against a foreign country. They were largely lawless, Dunkelman pointed out.

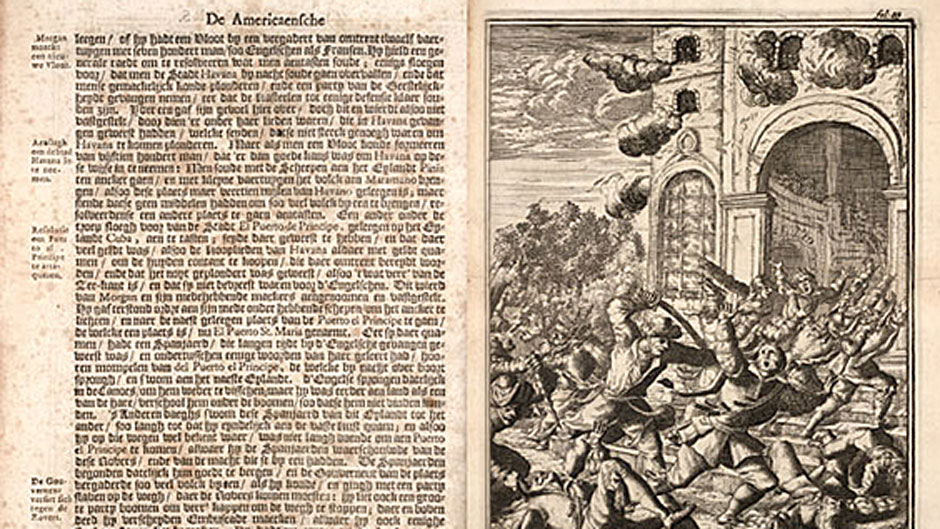

Dunkelman named Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin’s “Buccaneers of America” as “the greatest of pirate books” for its firsthand authenticity. The Dutchman was dispatched by the French West Indies Company to the Caribbean and served there for 10 years as a surgeon, meeting and attending to some of the leading figures at the time,” Dunkelman explained.

While Exquemelin’s book is extremely well-written, according to Dunkelman, the extraordinary engravings by an unnamed Dutch illustrator provide its endurable value. “The engravings are truly, truly dramatic and even a bit horrifying when studied closely,” he added.

During the Q&A session following the presentation, the curator noted that the pirates were “pretty democratic” yet adhered to a racial hierarchy.

“If you could hold a cutlass, swing on a rope, and knew something about being on a ship, you could probably join a pirate crew,” he said. “Yet there was no equality among pirates—there was a captain and officers; and as far as I know, they were almost invariably white.”

The golden era of the “brothers of the coast”—the seagoing swashbucklers bound by their dislike of the Spanish—spans a relatively short history, just 40-50 years in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, according to Dunkelman.

“This great age of piracy is like the cowboys—it’s romanticized and somewhat distorted in terms of greater importance than it actually was,” he said. “Most of the pirates were captured and hung—a popular activity, especially in the Carolinas. They were much more active than in Florida, in the 18th century they didn’t have a great deal of longevity. For most of them, 8-10 years was their career—they didn’t last as long as baseball players do today.”

Dunkelman indicated that during the several hundreds of years that pirates roamed the seas, more than tens of thousands of ships were lost. “And nearly every month some new shipwreck is found—some so deep in the ocean that they will never be recovered, but others closer to shore and that have been preserved and are waiting to be explored. It’s the delight of divers,” he said.

The gallery’s next exhibition will explore expansion to the West—the shift from ships to trains as a means of livelihood and as a form of excitement—and the building of the transcontinental railroads, marking a change from mom-and-pop local railroads to a system of control and standardization in the mid-19th century, Dunkelman noted.