Cuba has Santeria.

Brazil has Candomblé.

Jamaica still practices Obeah.

All are African religions brought by the more than 4 million people stolen from their homes to be slaves in the Caribbean during the 15th and 16th centuries.

University of Miami senior Kay-Ann Henry, who was born in Jamaica, decided to explore the ways that those enslaved people used the Obeah practices to try to liberate themselves.

One of six scholars who presented their research as part of the Library Research Scholars Program—one that allows undergraduates a deep dive into the University Libraries research collections and service programs—Henry presented her project, “How to Get Free, How the African Diaspora Used the Afro Caribbean Traditions for Liberation,” on Monday in an online presentation.

Motivated by the present mode of the United States, which is still reeling from police brutality, police shootings, and a chaotic presidency, Henry decided to look at history for lessons of resistance and liberation.

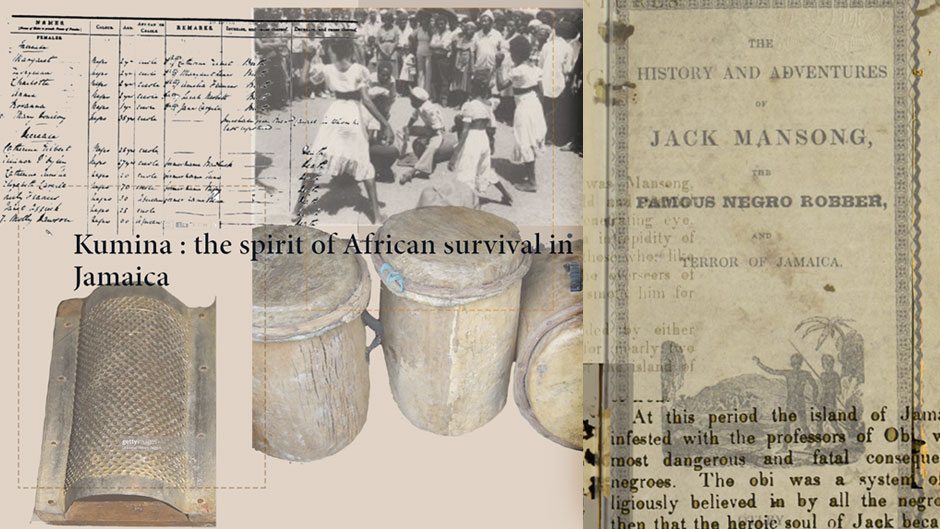

“In my quest to move toward liberation I was thinking of ways that we organically deal with the gems of the past,” she said. Working under the mentorship of Amanda Moreno, Cuban Heritage Collection archivist, Henry created a zine—homemade magazine—incorporating art, poetry, and photographs that detailed the history of Obeah in Jamaica.

“Kay-Ann is incorporating archival materials in a creative form of expression–the zine–to analyze African diaspora liberation movements in the Caribbean, delving into the themes of decolonization, enslavement, and cultural memory formation in the context of Afro-Caribbean religious practices,” said Moreno.

“Her interrogation of how her ancestors fought back against their colonial oppressors is especially timely work in the current context of increasing white supremacist sentiment and violence against Black, Indigenous, and people of color in the United States and around the world,” she added.

One of several religions brought to the New World by the Africans, Obeah relied on the connection with the spirit world and rituals for its powers. Unlike Santeria, which is still widely practiced in Cuba and the U.S., Obeah does not venerate deities or gods. Its rituals are shrouded in mystery, said Henry.

Those who opposed the religious practice referred to it as witchcraft, according to Henry. Anything that was “not the norm,” which was Christianity and Protestantism, was seen as dark arts, she pointed out.

“The religion is looked down upon in colonial times and also today,” said Henry. “Whenever there were riots against the British, it was used because it was a system of spiritual healing and justice making.”

Henry said that the first published mention of Obeah referred to a nanny called Nanny of the Maroons, an 18th century leader of the Jamaican Maroons (or escaped slaves), who led a long-lasting rebellion against British authorities.

“She was our first female heroine,” Henry noted. In the zine, she also highlights the work of Jack Mansong, a slave who used Obeah to “cause chaos on the island” by stealing food and other goods from the gentry class and freeing slaves.

Since photos and archival material on Obeah was scarce, Henry used her creative powers to enhance her project by adding short plays and poems that she created.

One of the poems, called “What Obeah does do,” reads in part: “Oil and powder, powder and oil brings all dis spirits and magic to a boil. This obeah ting ano play ting. But it could play you if you wish.”

Henry, who will graduate next week with a Bachelor of Science in communication, hopes that as she pursues a career in journalism, she can integrate all the lessons she has learned from this project into her writing.