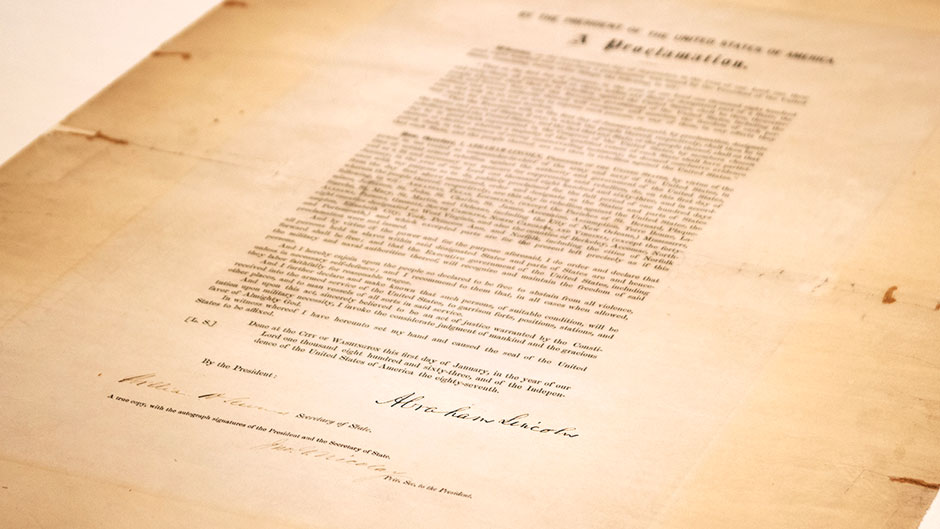

On June 19, 1865, about two months after the end of the Civil War, enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, were informed that they had been freed. This took place more than 2 ½ years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln. And since then the date has been celebrated by many Black people with picnics, parades, and family reunions.

In 1980, Texas became the first state to designate Juneteenth as a holiday, though the recognition is largely symbolic. Since then, at least 45 states and the District of Columbia have moved to officially recognize the day. Last October, New York and Virginia signed into law legislation declaring Juneteenth holidays in their respective states, according to The New York Times.

This week, both the U.S. Senate and House voted to make Juneteenth an official federal holiday, and President Joe Biden signed it into law on Thursday.

Jomills Henry Braddock, professor of sociology, and Donald Spivey, distinguished professor of history, Cooper Fellow of the College of Arts and Sciences, and special advisor to University of Miami President Julio Frenk on racial justice, reflect on the meaning of Juneteenth.

What did Juneteenth mean for Black people and how did they celebrate?

Braddock: Although the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1863, it was not until June 19, 1865 (Juneteenth) when enslaved African Americans in Galveston, Texas, learned of their freedom and that the Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia—marking the end of the Civil War. Across the U.S., African Americans continue to celebrate the occasion, in diverse ways. Unfortunately, important aspects of U.S. history have not been widely taught in schools, contributing to what might be labeled a mass public “mis-education” regarding the role of race in shaping much of the nation’s history.

Spivey: “Celebrate” is not the right word for Juneteenth. The date is commemorated in infamy as enslaved Africans in Texas only found out in 1865, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, that they were no longer supposed to be in bondage. Juneteenth can be used as a date to reflect on the institution of slavery in the making of America.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa race riots. Does Juneteenth carry a particular importance this year as we remember the devastation of that riot?

Braddock: In the context of the ongoing “racial reckoning” following the murder of George Floyd, Americans of all races are becoming increasingly attuned to the ways in which the history and lived experiences of African Americans are a central part of American history, not just Black history. As a result, more information is becoming available regarding many other race massacres (including in Rosewood and Ocoee in Florida) as well as other forms of racial violence and social injustices across the nation.

Spivey: Why should Juneteenth carry a particular importance because this is the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921? If the nation is serious, the discussion should be about reparations for Tulsa and for the enslavement and Jim Crowism that have been the heavy knees on the necks of people of African descent throughout this nation’s history.

Juneteenth started in Texas, and now we see a bill that was almost passed in Texas that would make it more difficult to cast ballots and would greatly affect Black people and other minorities. Are we seeing a resurgence of racism aimed at curtailing Black people’s civil rights?

Braddock: First, it is important to note that many of the voter suppression legislation policies (e.g., limiting early voting and vote-by-mail) that are being widely adopted, may disproportionately impact targeted groups (racial minorities, young people). Any such policies can also limit access to the ballot for others as well. Second, similar voter suppression legislation (e.g., voter ID card requirements) began to take root following the election of President Barack Obama. These efforts have continued unabated and became more widespread following the Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby vs Holder ruling, which eliminated important provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

A significant body of research indicates that racial resentment is associated with public support for voter suppression. There are many other contemporary indicators of a resurgence in attacks on the civil rights of African Americans (and other marginalized groups), including a rise in hate crimes following the election of both Barack Obama and Donald Trump.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that systematic efforts to restrict the rights of Black Americans have been ongoing since emancipation—Jim Crow laws, segregation, etc. More recently, the historic Brown v Board of Education school desegregation ruling has been virtually negated through several subsequent Supreme Court rulings. Similarly, the Voting Rights Act and affirmative action policies have been systematically undermined in the courts, which allows for states to engage in widespread patterns of voter suppression tactics or lead to persistent college enrollment gaps we see today. Additionally, other aspects of the Civil Rights agenda—fair housing and criminal justice—were never fully implemented or supported.

Spivey: The answer to all of these questions is “reparations.” What the recent events in Texas, Georgia, Arizona, and not let us forget Florida, tell us is that racism is alive and well in the United States of America and is likely to never be eradicated. Remember, 74 million Americans voted for Donald Trump, the worst president of the United States, hands down. What does that say to you? If half of the voting public can vote for four more years of him, it tells any thinking person that racism is as American as apple pie, systemic, and irreversible. Hopefully, I am wrong. Hope springs eternal.

Have we made progress or not?

Braddock: Considerable racial progress has clearly been made in virtually every sector of society. Yet, in most settings, racial equity remains elusive—education, employment, health care, housing, politics, sports, entertainment, and the like—due to persistent racial backlash and resistance. For example, the Brown school desegregation ruling has been virtually negated through subsequent Supreme Court rulings; similarly, the Voting Rights Act and affirmative action policies have been systematically undermined in the courts. Additionally, some aspects of the Civil Rights agenda such as the Fair Housing Act were never fully implemented or supported. In many ways, evaluating racial progress is analogous to assessing gender progress. Women have also clearly made significant progress in virtually every sector of society. Yet, gender equity remains elusive in most settings—education, employment, health care, housing, politics, sports, entertainment, and the like—due to deeply rooted persistent sexism and resistance to interventions focused on gender equity such as Title IX and the Equal Rights Amendment, which was never fully ratified.

Is Juneteenth being taught enough in academic courses throughout our school systems?

Braddock: Juneteenth is just one aspect of the nation’s racial history that is inadequately addressed in U.S. schools. The 240-year history of slavery, which Juneteenth represents, is also generally covered in a superficial fashion, if at all. According to a 2014 Southern Poverty Law Center analysis, states vary considerably in their curriculum requirements related to the inclusion of “Civil Rights” content. They suggest, for example, a few states (e.g., Georgia and South Carolina), received high marks for teaching about the civil rights movement, while many other states, including Texas, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Maine, received grades of D or F. Florida received a B grade.

What can institutions do to make sure that students know the importance of that day?

Braddock: Not to diminish the unique significance of Juneteenth, I believe that schools should offer a complete and unvarnished history of this great nation. For schools and educators to be equipped and empowered to provide that inclusive history, it will require building broad public support. As public education is locally funded and controlled, the federal government’s role is limited, especially with regard to curriculum content.

Other institutions, including politics, the media, and the corporate sector can play major roles in public enlightenment and in shaping public opinion. Just as many Americans first “learned about” Black Wall Street and the Tulsa race massacre through popular media—cable TV series “Watchman” and “Lovecraft Country”—many Americans were also introduced to the Rosewood massacre through a 2013 movie featuring Jon Voight and Ving Rhames. Interestingly, 2023 will mark the 100th anniversary of the Rosewood massacre.

While popular media can play an important role in heightening public awareness of historical events, they should not be considered a substitute for the deeper knowledge that public schools should offer. However, as individuals we all have a role to play in holding institutions, including schools, accountable. It can be done. In Germany, for example, children learn through their teachers and textbooks that the Nazi reign was a horrible and shameful chapter in the nation’s past.

Some people believe that July 4th should be the only date of emancipation that should be celebrated in the U.S. What do you think?

Braddock: I think that people who believe that should pause, reflect, and reconcile the notion of July 4, 1776, being the only important emancipation date with the reality that in the United States, African Americans were not emancipated until June 19, 1865—nearly a century later.

Spivey: Did slavery end on July 4, 1776? America has to own up to its true history. Only then can we even begin to think about building a more perfect union.