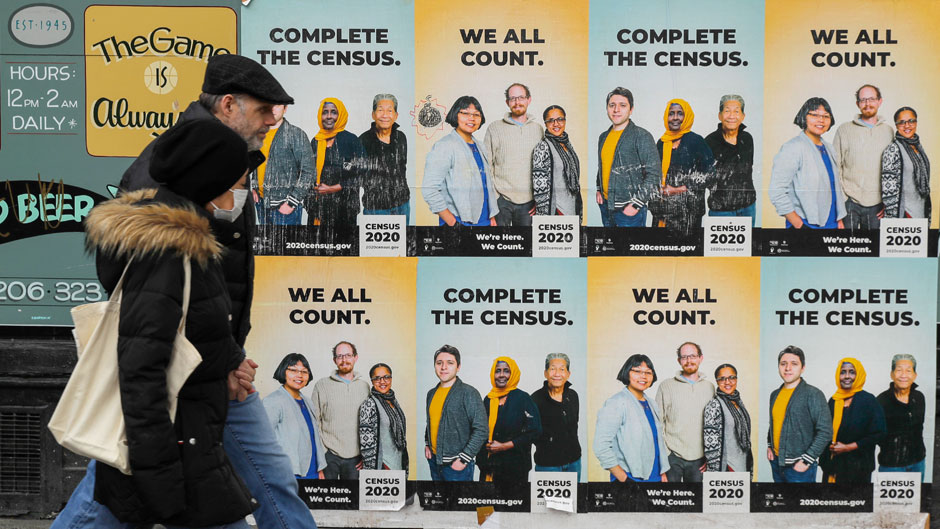

Recently released 2020 census data documented the ongoing trend toward a more diversified United States population—more Americans identify as multiracial, the number of Hispanics increased significantly with the accompanying downturn of the non-Hispanic white population, and the population blossomed because of immigration as the birth rate dipped.

While these shifts were expected, according to professor Ira Sheskin and associate professor Justin Stoler in the University of Miami Department of Geography and Sustainable Development, both demographers highlighted the political drivers and the implications for sociopolitical tensions as the significant takeaways from the 2020 data. Sheskin particularly noted changes to the census form and process that in likelihood influenced responses.

According to data from the 2020 census, the multiracial population, measured at 9 million in 2010, increased by 276 percent to 33.8 million people. The non-Hispanic white population fell from 63.7 percent to 57.8 percent in 2020, the lowest on record, driven by falling birthrates among white women compared with Hispanic and Asian women. The Hispanic or Latino population, which includes people of any race, grew by 23 percent to 62.1 million in 2020.

“This incredible diversification, particularly in urban areas, is not new,” noted Stoler, a geographer and epidemiologist. “These are population trends and local dynamics that people have been following, that continue to bear out, and that we expect to continue over the next decades. They’re shaping cities, shaping neighborhoods, and really shaping politics.”

Yet Stoler noted a concerning paradox—the trend of increasing segregation within the diversity.

“Cities are becoming more diverse, but people are increasingly living in neighborhoods where most people look like them,” he said. “So, it looks diverse on paper, but when you’re interacting with communities and neighborhoods, it doesn’t always feel that diverse. Some of these effects are part of the ongoing legacy of redlining and other segregationist policies.”

While Miami is the perfect example of immigrant neighborhoods, where residents often live in enclaves with those of similar ethnicity or from the same home country, this same pattern is emerging in midwestern cities where growth is not associated with immigration, Stoler pointed out.

The trend reflects how polarized we’ve become as a society, he said.

“If diversification also increases segregation, then it’s probably not helping,” Stoler said. “It’s not helping people learn to understand what it’s like to walk in other peoples’ shoes, to have empathy, to see the difficulties people face in stereotypes—and it probably only makes the tension worse,” he added.

“One of the mysteries of the 2020 data is if these patterns of simultaneous diversification and segregation are going to continue or are we going to see—what many people may want—diversity without the segregation,” he noted.

Sheskin highlighted the significance of the drop in the growth rate, which fell to 7.35 percent.

“Except for the Great Depression period of 1930-40, this is the lowest we’ve had in history,” he said, adding that this low growth bodes poorly for the economy. He explained the multiplier effect that population growth fuels: the need for new homes and the construction and materials needed to build them.

U.S. women are birthing fewer children—1.7 per, while the figure needs to average 2.1 for the population not to decline—he pointed out.

“This argues that if you want to grow the economy, either you have to convince people to have more kids or to allow in more—not fewer—immigrants and refugees,” Sheskin said.

The birth rate has dropped because women are waiting to have children and children are expensive, he explained, adding that policies such as free preschool could serve as incentives to reverse the shift. He indicated that the second pending infrastructure package before Congress, to be voted on in September, does include social infrastructure funding which speaks to this issue.

Sheskin, who teaches research methodology and has lent his expertise in developing error-resistant forms to the Florida State Attorney’s office, among others, referred to important changes between the forms used in the 2010 and 2020 census.

He highlighted the more crowded 2010 Census form that used a smaller font for the pages regarding racial identity as compared to the 2020 form, which provided a separate page for each person in a household and positioned a key identity question at the top of the page.

“There’s much more space [on the 2020 census] and the questions for indicating race and ethnic origin are more clearly visible,” he said. The 2010 census was filled out and returned by mail, while the 2020 census, still delivered by mail, was largely filled out online, he explained.

“We know that if you change the way you’re doing a survey—telephone, mail, or internet—you get different answers to some questions,” Sheskin said. “I do believe there was a significant increase in people being of two or more races, but I don’t think it was as high as the data indicate nor do the Census people themselves.” Sheskin attended a webinar offered by the Census Bureau in advance of Aug. 12 (data release date) where the agency reflected on the new information.

Stoler noted the societal responses to the fact that the U.S. population is growing more diverse.

“In places where the most rapid diversification is happening, such as in some of the swing states changing from red to blue, Georgia for example, we’re seeing this political backlash,” he said. “And it may get worse before it gets better. It’s in places where people feel threatened by diversity that socially and politically it’s likely to become the ugliest.”

Because of the way the census data is collected, Stoler suggested that the diversification is probably even greater than the recorded shifts.

But while the downside to these population shifts portends greater societal tension, he sees an upside.

“This is otherwise a wonderful trend that underscores what America is always supposed to be and to stand for—the melting pot, salad bowl, or whatever metaphor you want to use,” Stoler declared.