Only Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu can describe the first voting experience as something “like falling in love.” This gentle giant was a teacher, Anglican bishop, archbishop, Nobel Laureate (1984), fearless defender of the defenseless, and a voice of the voiceless.

He was an apostle of civil rights when the dogs of war had been unleashed on South Africans of color by a shamelessly white supremacist government that believed in separateness.

If there were a one-line summation of the life and legacy of Tutu, it would be that he opened his mouth for the voiceless who were under the heel of apartheid, a political system of racial discrimination that turned people of color in South Africa into second- and third-class citizens whose rights, if they had any at all, no white person was bound to respect.

What made Tutu an influential world-historical figure was his adherence to the principles of truth, righteousness, and morality—principles by which he lived and died. He used those principles to fight against the awfulness of apartheid and the gravy train mentality of the African National Congress, South Africa’s post-apartheid ruling government.

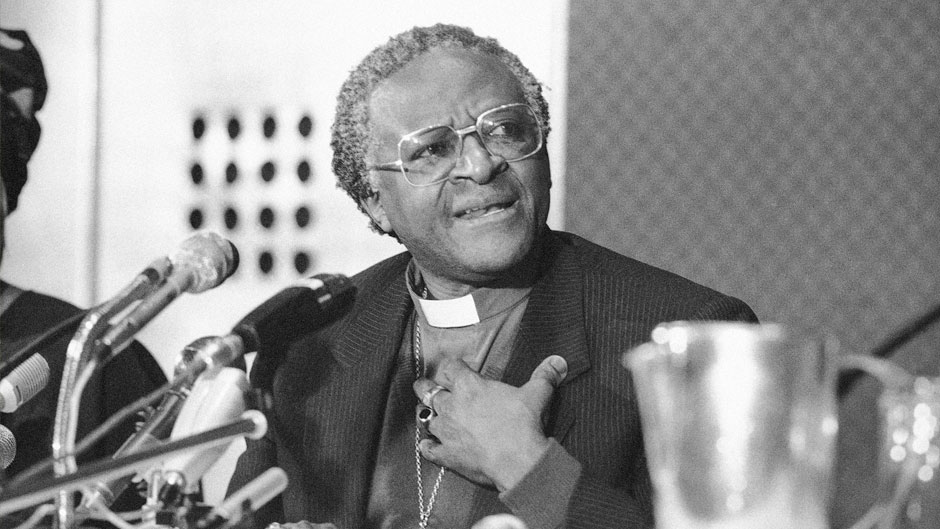

One surprising thing about Tutu registered vividly in my mind when I had the distinct honor of meeting him at Florida International University a few years back. From newspaper and television reporting of the work of this larger-than-life figure who heroically and courageously confronted the evils of apartheid, one gets the impression of an imposing individual and a commanding presence.

But the revered archbishop was relatively diminutive and often dressed simply in a purplish shirt and a clerical collar, sometimes topped with a suit jacket. The point? The simplicity and humility of so enormously popular an advocate of social justice, of equal rights, of the humanity of people, of a rainbow nation in which people of all races would proudly feel part of, and of the goodness of humanity (while cognizant of the evils of humanity) is overwhelming.

He was against the oppression of black by white and white by black. He personified a worldview animated by a popular African philosophy: “I am, because we are; and since we are, therefore I am.” By implication, ours is a shared responsibility and shared humanity. Any injustice or discrimination diminishes us all. That personifies the world champion of the rights of oppressed people that Tutu was.

The smiling archbishop—and I call him the dancing archbishop with the wicked sense of humor—has taught us what we can be, in our own right, in our work, and in our lives. He would ask us to see the humanity of people, eschew acts of intolerance, pursue knowledge in areas where we fall short—including bias—and nurture inclusiveness to make the world a better place for all. It is not for nothing that the University of Miami conferred an honorary doctorate degree on Tutu at the 2018 spring commencement ceremony.

A graduate of the University of Cape Coast in Ghana, West Africa, Edmund Abaka is an associate professor of history in the College of Arts and Sciences.