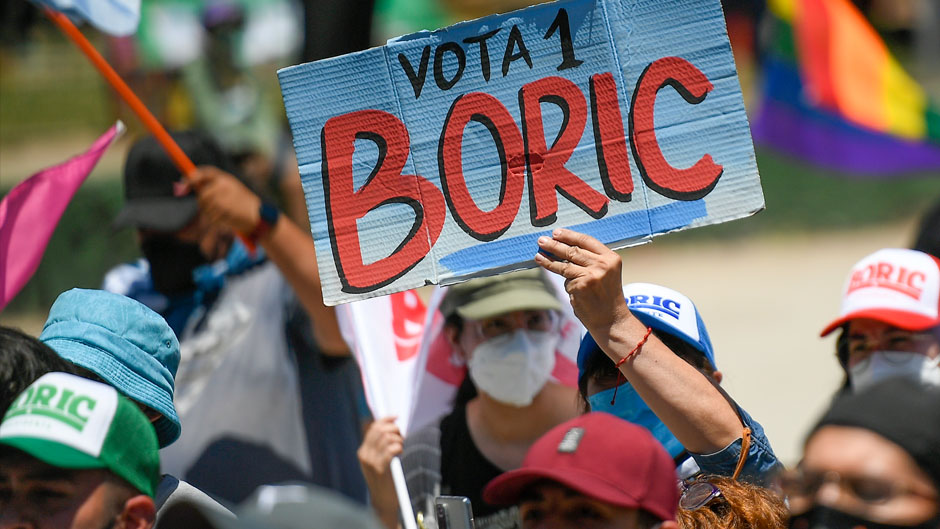

In late November 2021, Chile elected Gabriel Boric, a 35-year-old, as president. Boric campaigned on promises of ending inequality and addressing climate change. His win was preceded by two other elections of left leaning presidents in Honduras and Peru, pushing political analysts to say that there is a growing trend for these types of governments in the region.

A growth in poverty, unemployment, and economies that have been ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic have greatly affected South and Central America and the Caribbean. The total number of poor people in the region rose to 209 million by end of 2020, affecting 22 million more than the previous year, according to a report by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

A United Nations report stated that the “pandemic burst forth complex economic, social, and political scenarios of low growth, rising poverty, and growing social tensions.”

“Latin America has been really hard hit by the pandemic,” said Michael Bustamante, associate professor of history at the University of Miami. “The pandemic has exposed and worsened deeply entrenched economic inequalities that have never gone away, so it is not surprising to me that we are seeing a swing of the pendulum.”

Bustamante warns that although several left-leaning presidents have been elected recently, it is dangerous to lump all of them together as “leftists.” Each country has different histories that affect how the electorate has reacted, as well as the kind of political project each government represents, he pointed out.

“We should not lump all lefts under the same heading. What is occurring now in Chile, for example, is very different from what is occurring in Nicaragua or Venezuela or frankly any other country,” he said. Both Nicaragua and Venezuela have strict authoritarian regimes that greatly restricts civil liberties, as does Cuba.

In Chile, the election of Boric, a former student demonstrator, can be seen as the culmination of numerous youth demonstrations that asked the government for free education, an end to the country’s reigning neoliberal economic model, and a more equitable division of power and wealth. The country is also undergoing a revision of its constitution that goes back to the era of General Augusto Pinochet, a dictator who ruled with an iron fist for 17 years.

One of Boric’s challenges will be to carry out his agenda with a fractured congress, Bustamante noted, and at a time of macroeconomic vulnerability (because of the pandemic) rather than strength. Chile is attempting to redefine its social contract and what a social democratic political project looks like, he added.

In Honduras, leftist Xiomara Castro was elected as that country’s first woman president. She has promised to establish a national dialogue to pull her country out of poverty and tackle the street gang violence and extortion that has pushed a constant migration of its citizens to the United States. Her husband, former President Manuel Zelaya, was ousted from power under questionable circumstances in 2009 after he attempted to revise the constitution to extend his term.

The incumbent president, Juan Orlando Hernández of the conservative National Party, had been accused of benefitting from drug trafficking. “In Honduras, the government just voted out of power was deeply embedded in drug trafficking and corruption,” said Bustamante. “Even Washington acknowledged that this was true. So, it is not surprising that the left would sweep to power.”

In Peru, a provincial schoolteacher, Pedro Castillo, was elected president in July. His platform seeks a restructuring of the national economy to benefit the poor.

According to Bustamante, another factor affecting the electorate in Latin America is a strong degree of polarization similar to that which plagues the United States. “The left that is coming to power is doing so amid a kind of polarization that is more intense than 10 or 15 years ago,” he said.

Governments to the far right, such as that of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, have become stronger in recent years, he said.

Bolsonaro is accused of badly mismanaging the COVID-19 pandemic. At first, he claimed that the pandemic was “a little flu” and refused to take the virus seriously. About 620,000 Brazilians have died, according to Our World in Data. A congressional panel even recommended that Bolsonaro be charged with crimes against humanity.

He faces a presidential election in October against former leftist president Luis Inácio Lula da Silva. Recent polls suggest that if elections were held today, Lula would win with 46 percent of the votes against Bolsonaro’s 23 percent, according to Time magazine.

No one knows if the swing to the left will continue in Latin America, but Bustamante sees an opportunity for the United States to work with many of these newly elected leaders.

“The U.S. has an opportunity to show that it can get along well and partner as friends with countries of a progressive democratic left,” he said. “It would be a very good thing for U.S. standing in the region.”